Music fans of a certain age will recall the lost pleasures of album covers, and especially of box sets, which often included liner notes, lyrics, and interviews (and, of course, records). BJ�–RK (The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Artbook DAP), the catalogue for MoMA’s spring-blockbuster entertainment, recalls this form, with a slipcase containing four booklets and a slim paperbound book with poetic ruminations on the Icelandic star’s first seven albums along with images of the David Bowie–like array of her performing personae. But there’s no CD or DVD here, which makes this a little like a book about Monet without his paintings. Her remarkable music receives the informed attention it deserves only in an essay by New Yorker music critic Alex Ross—which, one hopes, the museum will make available online and to visitors—but otherwise this confectionary volume is strictly for fans. Why is there no electronic edition? Björk’s Biophilia iPad app is a landmark of that young medium, and her videos are outstanding; “All Is Full of Love” gets across in four minutes what her ex, Matthew Barney, might manage in four hours. Such a presentation could represent, convincingly, her multifaceted art.

Like the imagery in Björk, the paintings surveyed in KEHINDE WILEY: A NEW REPUBLIC (Brooklyn Museum/Prestel) derive from pop culture and fashion. Parodying old-school museum art, Wiley samples dusty masterpieces and genres to make remixes in which young, black, and beautiful models pose as those works’ subjects. Album covers generally, and Barkley L. Hendricks’s paintings specifically, provide the style: Photorealist portraits against elaborate, shallow, patterned grounds or overall colors. Wiley’s imposing Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, 2005, riffs on a version of Jacques-Louis David’s 1801 vision of Napoleon crossing into Italy. A young man in a camouflage outfit and Timberland boots sits astride a copy of the general’s horse; a background of gold-on-crimson wallpaper is swapped in for the sublime Alps. Wiley’s paintings depend on scale and elaborate framing for their impact (the images shrink, as the frames grow more prominent, in his recent riffs on Northern Renaissance devotional cabinet portraits), so it’s unfortunate that the book’s handling of the work is so timid and conventional. Despite considerable hot air from nearly three dozen testimonials—by a dealer, academics, critics, and even a curator or two—the art here still seems deflated.

City streets became like chaotic stage sets during the protests and provocations of the 1960s and ’70s, an era of wrenching urban changes that are the complex subject of THE CITY LOST AND FOUND: CAPTURING NEW YORK, CHICAGO, AND LOS ANGELES, 1960–1980 (Princeton University Art Museum), published by the Princeton Art Museum in collaboration with the Art Institute of Chicago. A handsome design by Project Projects—with sturdy front and back boards and a cloth spine to lie flat—gathers portfolios of art, photography, film stills, and period documents devoted to each city. The portfolios are each preceded by an essay (subjects include artists and urban planning, protest documentation, and post-urban-renewal design) and followed by short, focused writings on key individuals and topics. Today’s protests unhappily recall many images here: A man lying in the street during a 1963 CORE demonstration in Brooklyn, pretending to be dead; a faked gang killing on a nighttime East Los Angeles street in 1974, staged to provoke local TV news into reporting it in racist terms. Then as now, official violence could be frighteningly real: One notorious photo shows a cop, cigarette dangling from his mouth, about to club the news photographer Barton Silverman, who is taking the picture during Chicago’s August 1968 police riot.

The title of LARRY SULTAN: HERE AND HOME (Los Angeles County Museum of Art/Prestel) suggests a chasm that the photographer, on the evidence of this smart book, has spent a career trying to cross. “Here” is the setting of Sultan’s photographs, and those made or assembled during his decades-long collaboration with Mike Mandel. It is a realm of the “un-homelike,” the unheimlich, the uncanny. “Home” is what he persistently searches for in his pictures but never quite finds. Sultan was based in Northern California but found his richest material in his Los Angeles “Homeland”—the title of his ironic, politically pungent final series, made between 2006 and his death in 2009. Immigrant day laborers, hired by Sultan as “actors,” people these landscapes shot in outlying suburbs. His late photographs, generally printed at a large scale that captures fine detail, give us a world of tract houses, lawns, pools, and not-quite-natural nature that is at once familiar and disturbingly off. The sense of being at home yet not belonging is most acute in Sultan’s series “Pictures From Home,” 1983–92, featuring his mother and father, who enact a melancholy tale of declining California golden years. Sultan’s sense of surreal banality was honed in the projects with Mandel that conclude the book, notably the influential publication Evidence (1977), consisting of uncaptioned photos culled in the 1970s from police and fire departments and public archives.

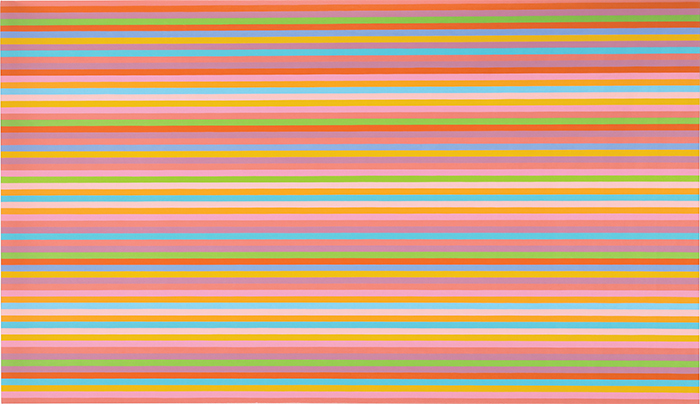

Two recent books illuminate with surprising scope the still poorly mapped realm of color in postwar art: BRIDGET RILEY: THE STRIPE PAINTINGS, 1961–2014 (David Zwirner Books/Artbook DAP) and DONALD JUDD: THE MULTICOLORED WORKS (Yale). Riley, still probably best known for the severe black-and-white Op art that made her famous in the 1960s, began to work in color in 1967. Lush and subtler than her earlier work, the stripe paintings in this volume are meticulously printed by Studio Fasoli, Verona, on heavy, supple stock. Two three-sheet gatefolds reproduce double-panel paintings, and a brief selection of works on paper, mainly studies, offers evidence of her hand, as do several actual-size details. Judd’s color work has long been neglected: The catalogue for his 1988 Whitney Museum of American Art (New York) retrospective has just one spread of his ’80s multicolor constructions. This new book, produced in the wake of a 2013 show at St. Louis’s Pulitzer Foundation, brings together period views of the extant or locatable examples, with texts by Richard Shiff, William Agee, and Judd (this a rambling meditation on color, among other things, written the year before his death in 1994). Judd, who had previously used no more than two colors in a given work, began using a palette of more than sixty hues selected from a standardized German “RAL” quality-assurance color chart. In other words, these are found colors; the work’s titles were provided by purchase order numbers—thus 84–14 is the fourteenth work produced in 1984. Both books, coincidentally, feature substantial new essays by Shiff, that stout foe of arid theory, who sees Riley and Judd as exemplars of artists for whom artmaking trumps critical conceptualization. Judd’s hands-off methods would not seem to qualify him as a proponent of making, but the works unquestionably realize his goal of a primary (not abstract) sensory art. Compared to the 1988 Whitney catalogue, in which several of these pieces—printed on a glossier, whiter stock designed for reproduction of shiny metallic objects—have a crispness and pop appropriate to Judd’s materials, the reproductions here are dismayingly flat and grayish. Colors, too, seem unstable in the present book, and since the actual RAL colors are easily available as swatches, it’s surprising that the images of the work were not more carefully color-corrected.

The titles of REMBRANDT’S THEMES: LIFE INTO ART (Yale), by Richard Verdi, a reading book (6.5 × 9.5 inches) unusual for its ample high-quality illustrations, and the exhibition catalogue REMBRANDT: THE LATE WORKS (National Gallery, London/Yale) raise the question of which approach offers the greater insight. The first undertakes an interpretive reading of visual narratives spanning the artist’s career, while the second is a period study, implicitly accepting the idea of Rembrandt as an example of “old-age style.” Focusing on self-commissioned works, Verdi examines Rembrandt’s biblical histories, as well as self-portraits and paintings of his intimates, aiming to penetrate the murk surrounding the painter’s biography. Verdi sees a reflection of the artist’s aims and preoccupations in his choice of subjects—his depictions of the Holy Family’s flight from Egypt, for example, reveal aspects of his changing relationship with members of his own family. Begun as a lecture series in 1986, the book is illustrated—so far as its format permits—by contrasting pairs of reproductions. But readers will often be obliged to flip back and forth to follow the visual argument—that is, they cannot compare works side by side but must keep an image of one work in mind while looking at another. Rembrandt: The Late Works, nominally about the last third of the painter’s career but including many earlier pieces, cannot decide whether it is a collection of scholarly essays or an exhibition catalogue. Asked to do two jobs, it does neither very well. It attempts to represent the London exhibition with a curated slice of Rembrandt’s oeuvre (using plates identified by catalogue numbers), and to illustrate (with images identified by figure numbers) slivers of that slice: There are fourteen separate essays on aspects of the work, ranging from dry but accessible biography to highly technical discussion. The parallel systems of illustration numbering are confusing for the reader, and reproductions mentioned in the texts are often difficult to locate. An obvious solution would have been an independent plate section representing the show, with essays illustrated by text figures and plate details. But both publications suggest a larger question: Might Yale, the largest art book publisher, which has recently undertaken a two-year project to create freshly designed, searchable e-publications of important backlist titles, also devote resources to publishing new art books in electronic editions? The goal would be to flexibly integrate images and texts, allowing authors and curators to engage with readers far more effectively.

Christopher Lyon is an art-book publisher in New York.