In 2012 Sue Klebold and her husband Tom popped up in Andrew Solomon’s deliriously received Far from the Tree: Parents, Children, and the Search for Identity, talking about their love for their son Dylan, who with his friend Eric Harris shot and killed twelve students and a teacher and injured twenty-four others at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado. Both seniors, they had been planning to blow up the school and kill many more, but the bombs they built didn’t go off. Sue Klebold said some rather startling things in Solomon’s book, such as “I am glad I had kids and glad I had the kids I did, because the love for them—even at the price of this pain—has been the single greatest joy of my life. . . . I know it would have been better for the world if Dylan had never been born. But I believe it would not have been better for me.”

The couple had earlier made themselves heard in a 2004 David Brooks column for the Times. Brooks found them “well-educated” and “highly intelligent,” mentioning in an aside that they had named Dylan after Dylan Thomas (clearly an indicator of intellectual cred). They described the day of the shooting in the terms of a natural disaster, like a “hurricane” or “a rain of fire.” This seemed less than appropriate, but Brooks, like Solomon, found them sympathetic. Solomon encouraged Klebold to write A Mother’s Reckoning, her book about her son, it is apparent. An agent was found, a publisher, and an editor and facilitator, rather an assembler, one Laura Tucker. Sue thanks her effusively. “Hundreds of pages of writing and thousands of hours of heartache might have died with me had Laura not transformed them into a publishable manuscript. During the years we have worked together, Laura has been much more to me than a writer. She has been midwife, therapist, surgeon, researcher, architect, navigator, workforce, spirit guide, and friend. She was both mortar and mason.”

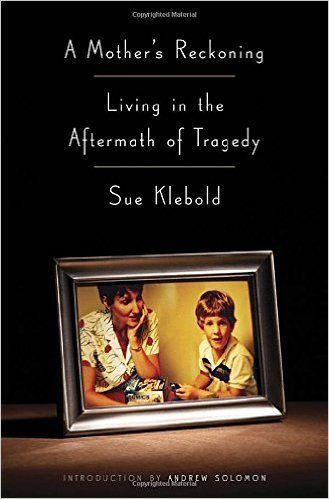

Andrew Solomon himself provides the introduction in his trademark manner of soothing radical anthropomorphism. He writes of the “nobility” of the book and praises Sue’s “refusal to blame the bullies, the school, or her son’s biochemistry.” This is not quite the case. She mentions a “toxic” atmosphere at the school, with its ruling elite of jocks and Evangelical Christians. She believes that peer cruelty was rampant and that Dylan was bullied, though she does allow that “bullying, however severe, is not an excuse for physical retaliation or violence, much less mass murder.” And “even if Dylan did endure humiliation at the hands of his classmates, it cannot absolve him in any way of responsibility for what he did.” As for not attributing his behavior to bad biochemistry, she seizes on an interpretation by a psychologist who suggests that Dylan might have “suffered from a mild form of avoidant personality disorder.” By the next page he is suffering from a serious impairment that causes him to indulge in the fantasy that he is a godlike being. She also takes comfort in conclusions that Eric was “a homicidal psychopath,” whereas Dylan was “a suicidal depressive.” Eric shot more times than Dylan, too. He killed more people than Dylan. Nine to four. Or maybe it was eight to five. Anyway, that psychopath killed more.

I can almost hear Laura Tucker saying, “Dear, I think it might be a good idea for you to insert here the grief over the destruction Dylan caused.” OK, Sue can agree to that. “I was never foolish enough to delude myself that Dylan was the only one who had been lost on the day he took his own life.” But she’d prefer to talk about placing his childhood stuffed animals in the casket before the cremation. “We placed them in the coffin so they rested against his cheeks and neck.” Or complain about the photo the press kept using. “The most terrible school picture Dylan ever had taken, so unflattering that when he brought it home, I urged him to have it reshot. It made him look like the kind of . . . guy you’d move your tray to avoid in the lunchroom. It didn’t look like him.”

She also wants to address some misperceptions about their house. It wasn’t a fancy house. It only looked good in those pictures taken from the air. When they bought it, “the pool didn’t hold water,” and the weeds growing in the cracks in the tennis court were six feet tall. There were mice! And that black BMW he drove was a mess! It was a clunker his dad bought for him for $400 and fixed up.

Father Tom, a pallid presence, doesn’t come up much in A Mother’s Reckoning. His most forceful action takes place early on. When first reports of the carnage at the school were coming in but the identity of the shooters was still unknown, Tom called a lawyer. He also figures in an incident a few weeks before the shooting as the Klebolds visit the University of Arizona. Dylan had, somewhat to the surprise of his teachers, been accepted there, and they were touring the campus. They had a lovely time but then Tom told his son that he couldn’t wear his beat-up baseball cap to the hotel’s breakfast buffet. Sue writes: “I was angry at him for harping on the hat. I guess I still am.”

This in marked contrast to Sue’s short-lived upset after viewing the secret tapes the killers had made of themselves screaming and cursing and fondling guns, sometimes in Eric’s basement, sometimes in Dylan’s own room. Dylan looked frightening indeed—monstrous—hard to cling to the pretty memories. But! “In truth, I was only blindingly angry with Dylan for a few days after seeing the tapes. I had to let it go. Anger blocks the feeling of love, and the love kept winning.”

In any case Tom has faded away pretty much completely. They are divorced. “We ended our marriage to save our friendship,” Sue announces in typically excruciating fashion. “The tension in our own relationship was rising” for years. And “it would only get worse as the sense of solace and purpose I found in the company of other suicide loss survivors grew.”

This—seeing herself as a suicide-loss survivor first and foremost—is the most egregious aspect of the book. When introducing herself at conferences, she says, “My son died of suicide,” and then adds, “He was one of the shooters in the Columbine tragedy.” As sleight of hand, casting herself as a suicide-loss survivor is pretty awkward, but it seems to have worked. She has been accepted by that tragic tribe and can even feel pity for some of its members. Regarding a “Celia,” she says: “Her own story broke my heart. She’d lost her son so young! At least I had been able to see Dylan as a young man.”

It troubles her certainly that Dylan participated (her word) in the events of April 20, 1999, but it bothers her too that the public persists “in seeing these acts exclusively as murders.” She complains of the traumatizing negative media attention in the beginning and the angry cries of “enraged community members.” Still, people over the years seem to have been remarkably tolerant of Sue Klebold. A clerk looks at her credit card and exclaims, “Boy, you’re a survivor, aren’t you?” Some of the stuff people say in these pages seems scarcely believable: “The petite woman threw her arms around me. She told me she’d raised boys, and knew how unbelievably stupid they could be.”

Indeed, boys can make some very bad choices. And Sue will grant that Dylan sometimes behaved selfishly—forgetting Mother’s Day, being cranky and neglecting to feed the cat. But she should probably say something about guns . . . “Dylan did not do what he did because he was able to purchase guns, but there is tremendous danger in having these highly lethal tools readily available when someone is at their most vulnerable. These risks are demonstrated, and we must insert them into the equation when we are talking about how we can make our communities healthier and safer.”

I can imagine Laura Tucker quietly suggesting ways to wrap this thing up. OK, Sue says. “If speaking with or meeting me would be helpful to any of the family members of Dylan and Eric’s victims, I will always be available to them.”

Seventeen years after Columbine, she can still generate a stifled sob and sniffle, as evidenced on the recent Diane Sawyer interview on 20/20. She suffers from anxiety and has to be vigilant in monitoring her stress. In A Mother’s Reckoning, she even tells us how she does it. Meditation, yoga, deep-breathing exercises, seeing a therapist, and taking antidepressants. She once was angry with God (“How could you do this?”), but she doesn’t feel that way much anymore. About your kids, you just never know. It’s all such a mystery! There are no easy or right answers. Or even questions.

Sue, we don’t find you responsible for the massacre at Columbine High School. But we don’t want to hear any more about your survival mechanisms, or your work on behalf of “brain health,” or your gastrointestinal issues (“My digestive system has always been my Achilles’ heel”), or the feeling you had on the day Dylan was born that a big dark bird of prey was passing overhead (we find that a bit of a stretch, actually). We don’t want to hear about the big goopy casseroles you shared as a family or his mischievous grin or how you got so mad at him for forgetting Mother’s Day and now wish you hadn’t. We don’t want to hear you describing yourself as a suicide-loss survivor. (That was really getting to us. As was your habit of substituting the words harmed or hurt for murdered or killed.) We don’t want to hear about you visiting the school library after the mayhem and before the remodeling, touching the carpet “that held him when he fell” and, before being “overtaken by tears,” feeling the “presence of children,” feeling “peace.” We don’t blame you or hate you. Really. We just wish you hadn’t written this offensive, self-serving, mendacious mephitic book.

Joy Williams is the author of Ninety-Nine Stories of God (Tin House, 2016).