The keen catalogue CONSTANT: SPACE + COLOUR; FROM COBRA TO NEW BABYLON (NAI010 Publishers, $40) inadvertently bathes the utopian artist Constant Nieuwenhuys (1920–2005) in a surprising light. It assiduously contextualizes his mildly bold, tidily irregular paintings, his three-dimensional wire and unusual-for-their-time Plexiglas constructions, and his visualization of “unitary urbanism” (a total human habitat where “life is a game” that merges “the science fiction of social life and urban planning”). Situationist International cofounder Guy Debord christened Constant’s plans for better-living-through-poetry environments “New Babylon,” though Constant didn’t stick with the Situationists for long. There is an affirmative, even (shh!) utilitarian spirit to Constant’s bright, forward-facing designs: Even his most way-out ideas, from “spatial colorism” to the aesthetic colonization of outer space, possess a department-store functionality. Trudy van der Horst’s bio of Constant places him squarely in the center of the artistic commotion of his age, but he somehow still seems a placid, well-meaning, trampled-over figure. Several of Constant’s short manifestos are reprinted here, and the one that sticks is called “Our Ambition Lies in Ambiance.” His weird yet stately Duchamp–meets–This Island Earth pieces, his set decor (for a ballet of Kafka’s The Trial!), furnishings, space oil paintings, and “art-chi-texture” all seem positively darling. They would enhance any living room, kitchen, sundeck, or study. If you saw them on Amazon or in Target, you’d buy ’em instantly. And you wouldn’t be that shocked to find them there.

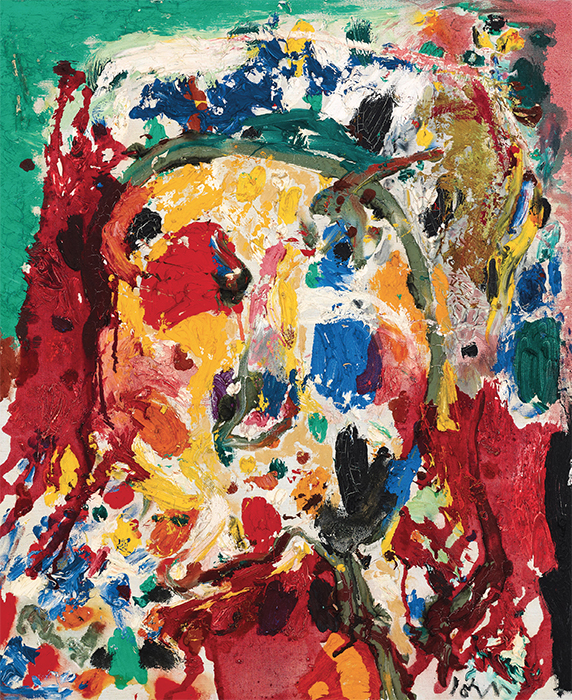

Dive into ASGER JORN: THE OPEN HIDE (Petzel, $45) and you’ll feel like you’ve tumbled into an alternate twentieth century where postwar painting (among other things) has been hijacked from under the noses of haughty gatekeepers by a bravura jester. On Jorn’s terms of sophisticated evisceration, “the process of encountering the unknown, the accidental, disorder, the absurd and the impossible” meant turning art inside out. Instead of creating showpieces to decorate the chic modern cathedral/stock market/penthouse, he concocted sinister, laughing cave paintings more suited to the playground or abattoir. This book gains much from its compression and concision: The expert text by Axel Heil and Roberto Ohrt elucidates the artist’s work about as well as any rational, “reasonable” appreciation could. It offers a good thumbnail biography of Jorn and his passage through Cold War times as a maker of all manner of haunting images, books, and spaces. He was a member of the Danish resistance during the Second World War, moved decisively forward as a founder of the Cobra (along with Constant) and the Imaginist Bauhaus movements, and became a key figure in the Situationist International. The Open Hide evocatively displays a body of work and ideas that is more flexible—and perhaps ultimately more durable—than the absolutist, anarchist-monarchist decrees of Debord himself. Jorn’s greatest accomplishment was not that he established the Scandinavian Institute of Comparative Vandalism after parting with the Situationists, but that in nearly every word, deed, and action, he managed to live up to the riotous implications of such an auspicious name. —Howard Hampton

In a 1980 drawing by Yvonne Rainer, a circuit-board-like design traces the influences of Merce Cunningham, John Cage, and the “ART WORLD” on modern dance since 1950. At the center is the name of their progeny, “RAUSCHENBERG,” as though he were the amplifier of creative signals from the twenty or so dancers and artists identified. This image, reproduced toward the end of ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG (Museum of Modern Art/Tate Publishing, $75), the volume accompanying recent retrospectives at Tate Modern and the Museum of Modern Art, has many of the same protagonists as MERCE CUNNINGHAM: COMMON TIME (Walker Art Center, $75), which documents this spring’s celebration of the dancer at the Walker Art Center. Rauschenberg was among the most important of Cunningham’s many collaborators, having served as the Cunningham company’s set, costume, and lighting designer for ten years, beginning in 1954. Reading the books together offers a fresh perspective on much of today’s art made, in the spirit of Rauschenberg, from “the stuff of the contemporary world . . . interdisciplinary in attitude and performative in implication or in essence,” as Leah Dickerman, co-organizer of the MoMA show, describes it.

Robert Rauschenberg considers the entire range of the artist’s production, more so than previous catalogues have. But this focus on his output should be tempered by an awareness of his characteristic ways of working and his larger goals. A monographic exhibition catalogue relies on the notion of a singular creator, but Rauschenberg’s art—like Cunningham’s—was rooted in active collaboration, with artists as well as viewers. His aim, evoked particularly well by Catherine Wood’s essay on performance and Michelle Kuo’s on Rauschenberg’s late-1960s organization Experiments in Art and Technology, was to create, as Kuo writes, “an art that would envelop and respond to the viewer—an environment of sensory plenitude and continuous change . . . an art that was intelligent.”

Merce Cunningham: Common Time, which has striking illustrations meant to evoke performance, does not follow the development of Cunningham’s career but instead organizes materials by type (e.g., essays, interviews, artist texts, and so on), though an extensive chronology is included. An essay by curator Fionn Meade explores Cage’s and Cunningham’s crucial realization that, as Cage once wrote, “underneath both music and dance was a common support: time.” This notion allowed the artists to produce work independently while sharing a creative space, and when Rauschenberg joined Cunningham, that space encompassed art objects, too. In a late interview, Rauschenberg called their idea “a kind of a theory of respect for nowness, essentially. . . . I’ve always worked in theater because of respect for the urgency of that particular moment, and existence in time. . . . I try to make art like that.” —Christopher Lyon

Born to a prominent banking family, Florine Stettheimer (1871–1944) never had to worry about money (and, like both her sisters, never married), and it’s tempting to interpret her poetry, paintings, and theater designs as expressions of the whimsy that such freedom allowed. (“I like slippers gold / I like oysters cold / and my garden of mixed flowers / and the sky full of towers,” she writes in one of her poems.) But her work is far more psychologically rich than its surface revelry—just look at the bonfire burning on the water in the undated oil-on-cardboard Fete on the Lake or the synesthetic colors of Heat, 1919. Eschewing the gallery/museum circuit, Stettheimer established a regular New York salon that also served as a “birthday party” to debut her most recent compositions, drawing a coterie of Jazz Age art and culture luminaries to her apartment and into her work. Her portraits of those famous friends—including Marcel Duchamp, Henry McBride, Alfred Stieglitz, and Virgil Thomson—portray them as androgynous, elongated, and arch; set within studio, park, and city landscapes that defy gravity and scale. Stettheimer didn’t sell her paintings and asked that they be destroyed after her death, but her sister Ettie (also a subject of hers) refused. Duchamp and McBride organized a show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1946; in 1995, she was the subject of a survey at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. To these few-and-far-between Stettheimer exhibitions we can now add this summer’s retrospective at the Jewish Museum, curated by Stephen Brown and Georgiana Uhlyarik. Its compact catalogue, FLORINE STETTHEIMER: PAINTING POETRY (Yale University Press, $45), provides a solid introduction to her life, scene, and art from both curators, along with the transcript of a lively conversation among seven women artists moderated by exhibition director Jens Hoffmann. “She staked out a place for herself beyond all categories,” artist Jutta Koether states in the catalogue’s final line, “and there is nothing more contemporary than that, I think.” —Prudence Peiffer

Call Louise Lawler one of the sharpest claims adjusters in the image business. Over her forty-year career—with an output that’s ranged from photographed portraits of artworks in situ to, most recently, black-and-white tracings of her own images—she has assessed and reassessed the volatile value and meaning of art and artworks, photography and photographs. She also accomplished all this without ever stooping to undermine art’s particular power or presence (as some of her Pictures generation colleagues have been wont to do). LOUISE LAWLER: RECEPTIONS (Museum of Modern Art, $60) is an elegant and engaging catalogue that accompanies the artist’s current MoMA survey, “Louise Lawler: WHY PICTURES NOW,” curated by Roxana Marcoci. Essays by Rhea Anastas, Douglas Crimp, Rosalyn Deutsche, and others offer platinum-grade thinking on Lawler’s most enduring subjects: art’s circulation, as well as its presentation and display; how an artwork can perform the political, and the coldly critical, while still radiating the personal; and how artist and viewer invariably conspire to produce a thing worth looking at and thinking about. Invigorating curveballs are thrown in essays by Diedrich Diederichsen—who cheekily writes about penning his contribution in proximity to a Lawler he owns—and Julian Stallabrass, who reminds us that Lawler’s work, though seriously brainy, is also terrifically funny. Take Monogram, 1984, Lawler’s now-iconic photograph of a Jasper Johns white flag hanging in a collector’s tony bedroom, where the sheets match the art—or is it the other way around? Author! Author! —Jennifer Krasinski

EXPLORERS’ SKETCHBOOKS: THE ART OF DISCOVERY & ADVENTURE (Chronicle, $40) is a volume that constitutes an eventful exploration in itself. This collection of seventy illustrated journals, mainly from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, tracks the lives of travelers who depicted temples, icebergs, flora, fauna, and people from around the globe. Familiar names—Bruce Chatwin, Gertrude Bell, and Ernest Shackleton—appear alongside lesser-known but no less adventurous journeyers such as Welsh widow Olivia Tonge, who began her travels after turning fifty; Canadian mountaineer John Auldjo, who immediately dozed off after summiting Mont Blanc; and Godfrey Vigne, an English lawyer who avoided harm in Afghanistan and Pakistan by drawing pictures for angry chieftains. As you might expect, given the prerogatives of imperial rule, nearly all these explorers hailed from the United Kingdom. But via their meticulous devotion to recording the nuances of unfamiliar lands and people, many of them exhibit a borderless passion that might be called cultural pluralism avant la lettre. Naval surgeon John Linton Palmer’s rendering of the body art of an “Easter Islander” suggests more than mere clinical curiosity. By attending particularly to the face of his nude male subject and capturing the man’s candidly aloof regard for the artist, Palmer mitigates any sense of exploitative voyeurism: This exchange is one between equals. —Albert Mobilio

Al Taylor’s artistic prowess was manifested in the careful offhandedness of his compositions. His sculptural assemblages repurpose sidewalk detritus, cast-off wood, and brightly colored broomsticks with an afternoon ease, as if challenging Vladimir Tatlin to a game of pick-up sticks. Taylor referred to these objects not as “sculptures” but rather as “drawings in space,” recalling the two-dimensional works the late artist began his career with. AL TAYLOR: EARLY PAINTINGS (David Zwirner Books, $45) surveys the little-seen abstract canvases he produced between 1971 and 1980, before switching over to the object-based practice for which he is now known. This lithe volume eschews analysis, opting instead to establish the art-historical pedigree for these works by turning to his inner circle for insights into his influences. A warm reminiscence between Taylor’s friends and fellow artists Stanley Whitney, Billy Sullivan, and Mimi Thompson is coupled with a personal chronology compiled by the artist’s widow, Debbie Taylor. The memories collected here—the Old English sheepdog named Wrecks; the obsession with Hawaiian music; the T-shirt emblazoned with Clement Greenberg’s face, worn when Taylor “wanted to start trouble”— offer a glimpse into the inner workings of the artist’s mind. But if the aim is to anchor his paintings, one need look no further than the reproduced excerpts from Taylor’s sketchbooks, which reveal the meticulous calculations underlying his seemingly improvised abstractions.

After Mary Wollstonecraft’s second attempt at suicide in 1795, the pioneering feminist’s new suitor, William Godwin, advised her that “a disappointed woman should try to construct happiness out of a set of materials within her reach.” In MOYRA DAVEY: LES GODDESSES/HEMLOCK FOREST (Dancing Foxes Press, $30), the artist applies a similar strategy to address the acute desperations of motherhood and mortality. The book presents the two titular pieces as a patchwork of photographs, film stills, and the artist’s own meditations, braced with citations from sources such as Goethe, Louis Malle, and Käthe Kollwitz. Chief among this chorus are the title figures of Davey’s 2011 film, Les Goddesses, that phrase being Aaron Burr’s nickname for Wollstonecraft and Godwin’s daughters and stepdaughters: Mary Shelley, Claire Clairmont, and Fanny Imlay. Davey forges parallels between these sisters and her own, turning the stories between her palms like two clay snakes rolled together until even the author herself loses track of their ends. Davey opens the text accompanying the film Hemlock Forest (2016) with a description of Chantal Akerman reading a letter from her mother aloud on film rather than answering it. Returning to Wollstonecraft’s own unanswered missives, Davey questions the consolation that letter writing can provide for women enduring the intimate disappointments of motherhood or sisterhood. As an extension of this tradition, the artist has taken to mailing her photographs to friends, which accounts for their accrual of creases, stamps, and stray bits of tape. At one point, Davey quotes Isak Dinesen: “The reward of storytelling is to be able to let go.” This book feels like Davey showing us her own folds as she loosens her grip. —Kate Sutton