“This is the Seinfeld cookbook,” Mike Solomonov explained to me earlyish one morning not too long ago. “It’s about nothing.” We were standing in the original Federal Donuts shop, which he and four partners opened in the low-slung, residential, and decidedly uncool Pennsport neighborhood of South Philadelphia in 2011. Sunlight streamed in through a plate-glass window emblazoned with the company’s red rooster logo, and the smells of sugar and coffee and hot fat were in the air. Steven Cook, one of Solomonov’s partners and a cofounder of CookNSolo Restaurant Partners, the pair’s mini empire of Philadelphia eateries, was behind a counter in a bright-blue apron. Surrounded by plastic quart containers of egg yolks and buttermilk, he was whipping up a batch of doughnut batter in a large metal bowl. Behind him a young woman attended to a slow line of customers, serving coffee and pulling doughnuts off a metal rack stacked with trays of the day’s six glazed flavors (the store also sells three “hot fresh” sugared flavors per day): peanut caramel apple, blueberry pancake, cinnamon oatmeal (Cook’s favorite), pomegranate tehina, crispy Nutella, and triple-chocolate.

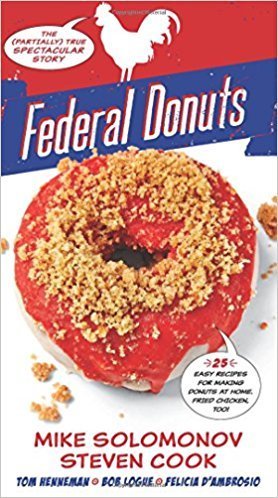

The cookbook in question was Federal Donuts: The (Partially) True Spectacular Story (Rux Martin/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $17), a kooky, drool-inducing little volume made up of far more than just recipes for the fried chicken and doughnuts—both of which come covered in various glazes and dry coatings—that the store purveys. It’s crammed with lore about the chain’s start and interviews with its founders, who appear throughout illustrated as bobblehead figurines; a parody workout routine that involves balancing a doughnut box while doing planks and lifting chicken sandwiches while squatting; a chapter on esteemed doughnut shops all over the country called “Donuts That Are Better Than Ours”; and, yes, a Seinfeld-ian airing of customer grievances about the store’s chaotic early days, when Solomonov and Cook were making most of the food themselves and washing greasy pots and pans in cold water, and running out of chicken was a regular occurrence. (“Working in here again is triggering me,” Cook announced from behind the counter.) This section reads like the very worst of Yelp. “The hipsters may have time for this, but I sure don’t,” snarked one self-anointed critic. “Really? You discontinued chocolate sea salt?” heckled another. “Were you bored with it? Because we paying customers were not.”

These days, Solomonov and Cook, along with their partners (Philadelphia coffee mavens Bobby Logue and Tom Henneman, and Felicia D’Ambrosio, who handles branding and social media) have long since proved the naysayers wrong. Not only is their food delicious, but they are also beloved. There are now five Federal Donuts shops (affectionately known as FedNuts), four in Philadelphia and one in Miami, and there’s one on the way in Nashville. It turns out that hipsters, and everybody else who loves doughnuts and fried chicken, have more than enough time for FedNuts. Plus, they have time to create tributes to the shops, some of which are reproduced in this cookbook under the heading “Fan Art in the Age of Federal Donuts.” There are collages of doughnuts, paintings of doughnuts, a drawing of an anthropomorphized doughnut with arms using a phone to take a picture of the fried chicken it is about to eat, and a pen rendering of Philadelphia’s city hall with the FedNuts rooster standing in for the statue of William Penn that is actually atop the building. “Fueled by coffee and fired up on donut glaze, the artists on [these] pages shared their vision of FedNuts’ place in the universe,” D’Ambrosio writes. “We are eternally grateful to everyone who makes Philadelphia a more beautiful place to be.” This outpouring of mutual love is what the book (and the store) is really about. I came for instructions on how to make strawberry-lavender doughnuts and za’atar spice blend and a chili-garlic glaze for chicken, but I stayed for the stories of all kinds about the community.

Solomonov and Cook are both chefs (Cook is a Wall Street refugee who escaped to the French Culinary Institute and shares two James Beard Awards with Solomonov, who has another two of his own), but their company is not just about good food. It’s also based on connections that go way back: “Mike’s mom was my wife’s middle-school English teacher in Pittsburgh,” Cook told me as I swigged coffee. “One of those teachers where you look back and say, ‘This person changed the direction of my life.’” In 2005, when Cook was looking to hire a chef to replace him at his first restaurant, Solomonov agreed to meet with him not only because of the family connection but also because “Steve’s the son and brother of a rabbi. I figured he’s got to be a reasonably good person.” An hour later, Cook had hired him.

Before long, the owner-chef relationship had evolved into a partnership, and Cook and Solomonov began opening restaurants. The first one that really stuck (though it, too, had a tough beginning) was Zahav, a modern-Israeli restaurant they launched in 2008. Then came a barbecue joint that they had to sell. Still, they couldn’t stop coming up with new ideas. “We just love opening places,” Cook said happily, as we watched his batter drop in rings into the hot-oil bath of the doughnut machine. “We’re always dreaming up the next harebrained scheme.” Federal Donuts came about in much the same way as their original working relationship—with a meeting no one really remembers much about. Not only that, but, as Cook recalls in one of the snippets of dialogue that fill the book: “Once we settled on donuts, I was like, ‘How do you make donuts?’ I remember Googling ‘donut machine.’” He sure knows now. As we stood over a tray of plain doughnuts and bowls of cinnamon and maple glaze, Cook showed me how to dip—“Put it in halfway. Now let it kind of drop onto your palm. You’re doing great!”—while he and Solomonov reminisced about the old days. “I would come in super early and pray we could get it up and running,” Cook said, grimacing slightly. “I wish we had day one and day two on record,” Solomonov added. “It would help with gratitude on a daily basis.”

By that point, Solomonov was working at Zahav until midnight most nights, then coming to the store to make doughnuts and prep chicken until four or five in the morning, when Cook would relieve him so he could sleep for a few hours before going back to Zahav. They couldn’t stay caught up on chicken or really anything else. On the second day the store was open, a famous food critic came in. “He was sitting here with his wife,” Solomonov said, gesturing to the few stools at the counter. “We had a thigh for him,” Cook deadpanned. “A thigh,” Solomonov said, sighing. “And he was very lucky we did. It was two or three o’clock, so we’d already been closed for, like, six hours by then!”

But in spite of the grueling hours and the mounting pile of broken doughnuts in the compost bucket, something was right. “The droves were still coming in,” recalled Solomonov. “There was an electricity and magic to this. We’d never experienced critical success that quickly and that organically.”

They lacked space, though. On my visit to that first store, when it came time for us to switch from glazing doughnuts to frying chicken, all we had to do was turn around to face the other wall. Because they had no room to butcher, Cook and Solomonov were buying their chickens already cut up, which was problematic for quality control. By 2013, the company was successful enough to expand operations into a dedicated commissary, and they began ordering whole chickens. But they had a new problem. “We had five hundred to one thousand pounds of chicken bones going to the dumpster every week,” Cook explained.

The partners thought of making soup with their leftovers and donating it to Broad Street Ministry, a charitable organization they were already volunteering with, which provides meals, an address, and much more to Philadelphians in need. “They hated that idea because they’re always fighting the stereotype that they’re a soup kitchen,” Cook explained to me as we began sampling a batch of fried chicken with chili-garlic glaze he’d just fried up. “So we went back to the drawing board and came up with the terrible idea to open another restaurant.” This new one would be something entirely different, though: 100 percent of its profits would go directly to Broad Street Ministry’s Hospitality Collaborative. Rooster Soup Company, which is fully supported by Federal Donuts, opened in Center City in January of 2017. “Federal Donuts has always had a special connection with Philadelphia,” Cook told me as we reached for more chicken. “It’s always been very in touch with the city and the customers, so we wanted to do something to further that relationship.” Or, as he and Solomonov write in Federal Donuts, “The restaurant is located steps away from the city’s political, social, and economic centers, a deliberate decision to live in the middle of the conversation on how we deal with the intractable problems we face as a city. It’s a place where people can make a tangible impact on their community. It’s a place where food waste is converted into social action. It’s a place to receive hospitality and a place to pass it on.” That’s a pretty substantive idea for a book about nothing, and it’s perfectly in keeping with the FedNuts approach to life. As Bobby Logue says in Federal Donuts, “I think each one of us loves Philadelphia. . . . My favorite thing is just standing out on a Saturday morning and watching a half dozen kids come in with their parents and just smile. . . . That alone is enough. Even if the business failed, it would have been enough that thousands of kids came through here and had a blast. You know?”

Melanie Rehak is the author of Eating for Beginners (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010).