Years ago I led a seminar on Korean literature and wanted to show a film to the mostly non-Korean students. This was before South Korean cinema was fully established as the darling of film festival juries and adolescent boys everywhere, so I drove to my local Blockbuster and pulled out the only VHS cover I saw indicating electricity had found its way to Seoul. “This will give you a glimpse into modern South Korean life,” I announced to my class about 301, 302, which did indeed show Seoul as a First World consumerist dream housed within tall, concrete apartment buildings. It also showed one apartment resident literally consuming, as a stew chased by red wine, the expertly butchered flesh of her neighbor.

I won’t make the same mistake here. Although “Gangnam Style” and North Korea’s nuclear threats have been replayed in our media, relatively little is known, outside of Asia, about Korean culture and contemporary life. It’s tempting, then, to talk about a poet such as Kim Hyesoon—who has several well-received books translated into English and is a favorite of the international literary festivals—as being representative of Korean history and of all aspects of contemporary Korean culture that we don’t yet know but should. We could even claim that Kim, born just after the Korean War, grew up in tandem with South Korea: She was raised in a war-torn, developing nation; protested alongside her university classmates against the military dictatorship; witnessed the rapid modernization and techno-bureaucratization that swept South Korea into the twenty-first century; and is now a celebrated writer in the most wired country in the world. Can’t her writing be our glimpse into modern Korean life?

Even Kim’s preoccupation with violence—like the description of fetuses as “chunks of freshly grilled flesh inside a vagina” from her earlier Mommy Must Be a Fountain of Feathers—seems to align with a distinctly Korean taste for guts and gore. This is a cultural characterization that has been propagated by the “extreme” films dominating South Korean cinema’s international reception, such as Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy or anything by Kim Ki-duk, and video games with names like Blade & Soul and Requiem: Bloodymare. However, we might consider whether this is actually a Korean taste or what, of Korea, the rest of the world has preferred to consume. “Love that is about a hole, a hole for the benefit of a hole, according to a hole. I use the hole as I pretend to talk about love,” Kim writes in All the Garbage of the World, Unite! As delightful of an ars poetica as this makes, how unjust it would be to read Kim’s writing as “representative” of a national culture or aesthetic.

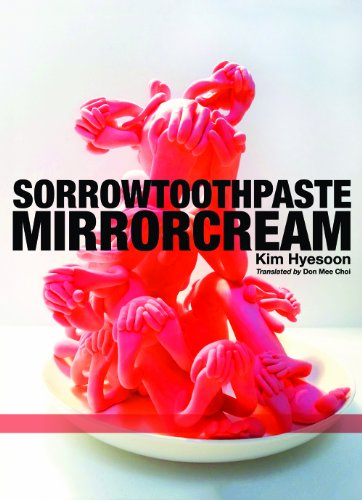

Kim’s most recent book in English, Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrorcream (Action Books), is adeptly translated by Don Mee Choi—as were Mommy Must Be a Fountain of Feathers and All the Garbage of the World, Unite!—and it combines Kim’s 2011 Korean collection Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrorcream with 2012’s long poetic sequence I’m OK, I’m Pig! It also includes a lecture and two interviews as appendices. In one of these interviews, Kim reveals that I’m OK, I’m Pig! was partly inspired by her reading of The Record of the Barbaric Times, a history of torture in Korea. Of course this is immediately, viscerally intriguing, and it plays well with the morbid excerpt from the poem “Marilyn Monroe” featured on the book’s back cover: “We return as hot pigs/ We return for our final act/ The act in which our fingers rot even before we lie down in our coffins.”

Rotting, as well as bleeding, vomiting, and a whole slew of other discomfiting gestures, is a well-established motif in Kim’s earlier writing, and this gross-out sensationalism undoubtedly plays a role in her work’s traction with English-language readers, especially those looking to be edgy and current. Decades of shock art have taught us that there’s nothing more radical than effusive body fluids, and nothing more bourgeois than being squeamish about them. To be fair, for Kim, who began publishing her poetry in the late 1970s and is one of just a few women ever included in anthologies of Korean literature, the politics of this aesthetic are clear: It’s a provocative reaction against the precise and hygienic male verse that long dominated Korean poetry—a disembodied lyric that projects its pathos onto the landscape or an overlooked creature (snails are popular), and then neatly concludes with an aphorism. Here, to be the object of the male gaze is not just to be the object of his desire, but also his vehicle, his avatar. Kim wrests her poetry away from this unilateral mode of perception, which keeps its objects contained and controlled at an arm’s distance, and instead performs the collision and collaging of fully felt bodies, particularly the speaker’s own. This isn’t to say Kim doesn’t have her own array of familiars (pigs, rats, garbage, even manholes), but she proffers her body for their use as well. And above all, she makes us keenly aware of how they resist.

This is why violence prevails in Kim’s poems. It effectively shifts poetry’s perspective away from what is observed to what is felt, while it also forces us to recognize bodies in conflict and, subsequently, bodies in resistance. But artists who employ guts and gore, and stabbing and scissoring, in their work walk a fine line: A powerful means of opposition in one context can come across as gimmick in another. In Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrorcream, Kim steps back from that line, despite what the “Marilyn Monroe” excerpt might have us believe. We find less bloodshed in this collection than surrealist absurdity, riffs on pop and literary culture, and surprisingly humorous critiques of our global (not just Korea’s) society of the spectacle. Kim hasn’t lost the rage or daring that fueled her earlier books, but in Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrorcream, her macabre exuberance is countered by a more meditative melancholy, and it makes us see more clearly, and more inventively articulated, the politics of perception underlying her turns to violence.

The book’s title comes from the poem “The Poetry Book’s Open Window,” which begins by situating the speaker in a St. Louis hotel called Cheshire Inn. This name leads Kim to the following associations: “as in a fairy tale the Cheshire Cat lives in the hotel/ While I was watching Up in the Air in my room/ George Clooney entered a pitch-dark theater/ and jumped up like the Cheshire Cat.” Within the poem’s first six lines, a complicated network of allusions, metaphors, similes, and puns arises; everything is connected to everything else, but the nature of that connection always varies, and the tenor-vehicle line of figurative language flips into a Möbius strip. St. Louis recalls Lewis Carroll; the Cheshire Cat lives in the hotel as he lives in a fairy tale; the speaker has been up in the air, in an airplane, to get to St. Louis, while now she watches Up in the Air, and we inevitably think of the Cheshire Cat’s disembodied smile hovering up in the air in Alice in Wonderland; the fairy tale/hotel room becomes a pitch-dark theater; and that disembodied smile now belongs to George Clooney projected from the television, moving like a cat.

But still we’re not done. Kim continues, “My comb called mirror and mirror called light and light called me/ Locked inside my sad eyes locked inside the mirror locked inside the room, I put on/ mirrorcream and get slowly erased.” A calling out flips into a locking in, just as putting on cream leads to erasing, not enhancing, oneself. The speaker, disappearing piece by piece, becomes the inverse of the apparating Cheshire Cat, as does everything around her, until she ends up “staying in a room of loss,” a world that appears to be the negative of ours. Then we realize, however, that this negative world is the one whose methods and metaphors make sense to us— where the moon’s appearance in the sky is more intuitively described as cream smeared onto an erased face—rather than the previous one carrying objects called sorrowtoothpaste and mirrorcream. Perhaps, then, we are the permanent tenants of the “room of loss.”

Such complicated correlations and inversions in perspective flourish in Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrorcream, and we often are left asking ourselves who is acting on whom, who is speaking for whom. Choi’s translations excel, in fact, in how she allows the language to perplex us; she is unafraid of sacrificing the coherence of English grammar if she can maintain a trace of Kim’s linguistic play. In the book’s opening poem, “Dear Choly, from Melan,” Kim not only personifies melancholy, she splits it into two separate and not always compatible, nor complementary, beings:

Melan covered herself with a cloud, Choly with a shadow

Melan endured the wind, Choly clung to the sea

Melan said It’s flesh-scented, Choly said It’s water-scented

Melan disliked sunlight, Choly’s feet were cold

Melan didn’t eat, Choly didn’t drink

I was absent with Melan ate, also when Choly drank water

By the time we get to the book’s final sequence, I’m OK, I’m Pig!, we find that the two entities split but still circling each other are the “I” that claims it is OK and the “I” that claims it is Pig. “I’m OK” is exemplified by the “Venerable monk! Wall-staring monk!” who sits meditating in a Zen room, back turned to the world, willing herself to be okay, to be just fine, while its counterpart, the predictably carnal “I’m Pig,” stirs up all the rotting, bleeding and vomiting that have been Kim’s trademarks. Pig “lies down, its nipples on top of shit;” Pig claims, “I can taste my own tongue as I get mashed up;” Pig’s nights consist of “internal organs raining down from the sky;” and Pig is a “repulsive woman, smelly woman, crazy bitch, smacked bitch.”

But if Pig is filthy and repulsive, it is because of what has been projected onto her and how her “Masters” have long treated her. Kim recounts in the book’s appendices that in South Korea, between 2010-2011, “three million pigs were buried due to the outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in our country. . . . Their pink bodies, whether they were diseased or about to be diseased, were difficult to dispose of, so they were buried alive.” Pig becomes the grotesque stand-in for those that have been beaten, used, discarded and silenced—and those that have given birth, taken life, lost life, and suffered. But even this role, as stand-in, is one Pig resists and only takes on if we suffer through the violence too. “Anyway, to nail Pig on a cross would be too natural, meaningless,” Kim writes. Don’t expect Pig to hand us our redemption. Only through confronting Pig’s physical suffering, rather than emulating the ascetic monk’s wall-staring, do we begin to attain that spiritual ideal of empathy—an empathy that is visceral and fully felt but still withholds itself from consuming its object. I’m not OK, nor am I really Pig, but by hearing Pig “cry in the grave,” “cry standing on two legs, not four,” might I redress the former.

In reading the criticism on Kim’s poetics, I’ve been struck by how often the same bullet-point history of South Korea is recounted: the Korean War, the military dictatorships, the Gwangju Massacre, the nuclear race. The implication is that Kim comes from a bloody culture, so how can she help but write bloody poetry? Having a mother living in Seoul, born the same year as Kim, who has never seen Oldboy but delights in her daily melodramas—where a scene involving hand-holding and violin music can send viewers into ecstasy—I would say that Kim is no more predisposed by her context to such violence than Billy Collins or Charles Bernstein. After all, we could say that their context comprises of over 30,000 gun violence-related deaths each year and a president who announces on television, “We tortured some folks.” Let’s not glorify gruesome violence as an exotic aesthetic, nor blind ourselves to its proximity and prevalence. Kim is a singular poet in Korea, just as she is in America, but we can only fully appreciate this when we see that, for her, such violence is not the end but a means.

Mia You is a doctoral student at UC Berkeley and the Central Editor for Poetry International (Rotterdam).