Since the invention of messianism, every generation, regular as clockwork, wonders if it might be the last. History is planted thick with prophets of the end times: John of Patmos, David Koresh, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Some make for better reading than others.

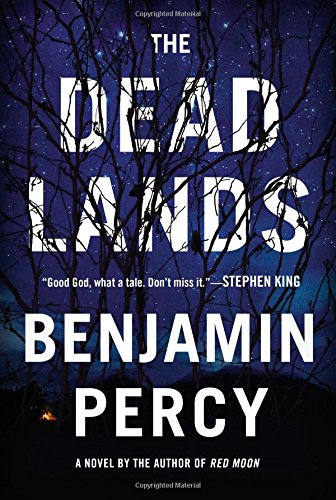

Mass death and destruction are unfortunate, but fiction writers find them nifty all the same. And if the last few years have seen an especially strong renaissance of apocalyptic literature, Benjamin Percy’s impressive new outing, The Dead Lands, takes the form into its mannerist phase. Loosely adapting Lewis and Clark’s journey west, the book opens in what was once St. Louis. A century and a half have passed since humanity was ravaged by a pandemic—and, adding insult to injury, much roasted by a substantial nuclear exchange. Few believe in life beyond their walled city, Sanctuary, when from some foreign land a strange rider arrives. A guide named Gawea.

In theory, what follows is a road story. A town ruled by water and cancer, Sanctuary is very much worth leaving. Gawea carries an invitation to that effect. Several take her up on her offer, an expedition to seek out Oregon: Lewis Meriwether, a troubled inventor who curates the city’s museum; Wilhelmina Clark, a disaffected sentry on Sanctuary’s walls; and useful types of the usual sort. They encounter difficulties of the fantastical variety along the way. Familiar, no? But in practice that central arc is pointedly artificial, stretched distinctly beyond realism or naturalism. The plot turns out to be a little beside the point. The Dead Lands is really the stripped, buffed skeleton of a road story, set up to show off—attractively—an enormous quantity of decorating tropes.

The Dead Lands masquerades as a conventional novel for much of its length, though an unusually hungry one, cannibalizing motifs from Lewis and Clark, J. R. R. Tolkien and Neil Gaiman, Civilization and Fallout. But stuffed with all those stylized citations, the book reads in retrospect more like a narrative encyclopedia, or better yet a narrative map—something after the style of a Roman itinerarium. Percy nods at this from the beginning, citing Gaiman for an epigraph: “All stories are in conversation with other stories.” And he returns to the idea late in the tale (more bluntly than he should have). Percy’s villain says of books, “They are following a predetermined pattern, often one established by another writer, or another hundred writers, or another thousand writers, so that every story might seem unique and particular but is actually recurring, in conversation with others.”

It’s refreshing when Meriwether replies, with verve, “I prefer nonfiction.”

As a writer thoughtfully renovating apocalyptic tropes, Percy joins good company. Once thought of as kitsch and literal in its sensibilities, eschatology has been colonized by writers with degrees from Iowa, and prizes from esteemed literary institutions, too. One riotously well-paid scout for literature’s weird turn was Justin Cronin; his 2010 re-imagination of the vampire, The Passage, earned him, it was widely reported, millions. Others with great talent have done work in the genre too: Colson Whitehead with Zone One, Emily St. John Mandel in Station Eleven. When it comes, the End of Days will be well novelized. For his part, Percy boasts a Plimpton Prize from The Paris Review and a Whiting Writers’ Award.

So the novel’s interests are stitched together by fine prose, generally excellent prose, sometimes really striking prose. Beyond Sanctuary the world grows from vile, lovely nature writing. Gutting a massive catfish, the explorers “find a beaver inside, swallowed whole and socked by yellow jelly, like some malignant birth.” Tumors sneak into sentences, metastasizing. Our heroes “kill pheasant, grouse, possum, rabbits, rats, sheep, coyote, deer, antelope, some mutated and some with cancers blooming like mushrooms inside them.” Everywhere bodies go wrong, irradiated; some of this world’s survivors worship at a nuclear altar, and they look the part. Each sports some gorgeous deformity: “A second set of teeth barnacling their shoulder. Cysts bulging and sacks of fluid dangling. Moles so plentiful that a body appears like some fungus found in the forest.”

Biology is the book’s irresistible idiom. It even mediates, with some success, its internal diversity of image, genre, and pace. Sanctuary, otherwise the book’s least evocative setting, is most beautiful when most in touch with the dominant style, “covered with a dusty skin and seeming in this way and many others a dying thing, its windows and archways hollowed eyes, its streets curving yellowed arteries, its buildings haggard bones… ” Bits of the book less in tune with that aesthetic inevitably have trouble integrating. Magic, for one. Meriwether has temperamental psychic gifts and a programmable clockwork owl, both rendered in clean lines and clean language. Gawea is in the employ of a more powerful telepath, Aran Burr, who moves his servants about like so many synchronized swimmers. And if the clash of this artificial mode with the book’s organic passages is partly the idea, it still takes a toll on the novel’s forward momentum.

For better or worse, this is a habit of The Dead Lands: it swaps in abstract pleasures where immediate ones would usually be. The book seems at times sarcastically hostile to narrative satisfaction. Not far from the end, Meriwether gropes for “all the energy that made them press across what felt like an interminable nothing, now dissipating, in danger of being lost all together.” And if Percy isn’t being entirely fair to his own book here, his tongue isn’t entirely in cheek either. The expedition moves in jumps and skips and slogs, but rarely with determination. If obstacles vary in scale, the emotional stakes don’t often budge. The characters sometimes defy investment. Energy is not the chief virtue here.

But there are many virtues, strong and unusual ones, strange and worthy. For all of Percy’s declared influences, I wonder if he doesn’t owe more to Bosch or Bruegel. All three work in a similar mode, and all make dictionaries of the grotesque. Mileage will inevitably vary; the aesthetic is an acquired taste. But the result also feels satisfyingly productive. Apocalyptic literature is developing new twist and turns, and The Dead Lands moves that ball forward, in its odd and deliberate way. The book seems timely in that respect. If prophecies are always hanging over human heads, they hang especially low today. The Dead Lands reminds that these bad dreams are old dreams, hand-me-downs all.

Grayson Clary lives and works in Washington, DC.