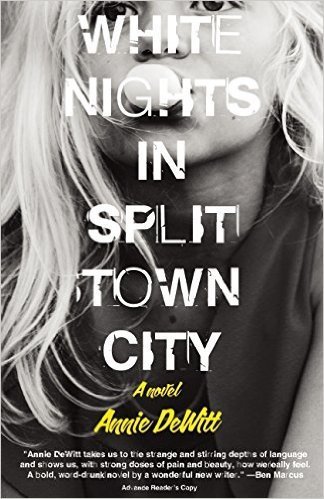

It is fitting that White Nights in Split Town City, the strange and striking debut novel by Annie DeWitt, opens with “When” by Sharon Olds, a poem that pairs atomic dread with the familial. A young mother hears a “noise like somebody’s pressure cooker / down the block, going off.” Holding her small daughter, she steps outside onto the lawn and sees a bright ball in the sky—they watch it “rise and glow and blossom and rise.” Surprisingly, the poem ends not with an image of apocalyptic terror, but one of grace: the child reaching up, arms open to the searing light. White Nights is the study of a failing family—how it is dismantled from within, how it is threatened by the world outside. DeWitt steers headlong into the most intimate and uncomfortable aspects of this disintegration, but, like Olds, she shows the glory in the terrible, the beauty in the bomb.

It’s the summer of 1990 in rural New England. Desert Storm rages on the nightly news, Ryan White has just died of AIDS, and twelve-year-old Jean’s family is in a state of collapse. Her father has been getting a little too close to a female neighbor and he’s started carrying a bottle of liquor in his pocket. Nights, he takes a pillow out to the porch and screams into it. Jean’s mother, feeling isolated in both her marriage and their tiny town, hires contractors to “bl[o]w the house out” and replace the entire back wall with windows. “In a glass home,” she says, “you are so much closer to the reality of the world.” But it’s not enough—soon after the renovation is complete, she heads upstate to take “a little breather,” leaving Jean and her sister Birdie motherless for the rest of the summer. Neighbors and “a train of women” babysitters are put in charge of the girls while their father works, but Jean, the elder by several years, is largely left to make her own fun. Though this sounds like the set-up for a traditional coming-of-age story, DeWitt takes this premise into new, truly surprising territory.

Most mornings, Jean wakes “to the sound of horses kicking the insides of their stalls.” Some unidentified, mosquito-borne pathogen is killing the animals, and farmers have resorted to keeping them confined until well after sunup, when the risk of transmission is lower. Pleasure-seeking Jean is also trapped, too young to act on her desires. Flat chested and gangly from a recent growth spurt, her summer uniform is a white bathing suit with cutouts down the sides, fastened together by pink buttons. She’s chosen this suit specifically for its allure, and calls the skimpy one-piece an “untouchable combination.” It’s an expression she’s heard used in relation to dogs; how disparate breeds can be combined to create an animal both wholesome and powerful—“a good, kind dog with a strong snout.” And that’s Jean nutshelled: Golden Retriever and Doberman, child and adolescent, modest temptress. “You don’t look at people like that,” her mother has told her more than once. “It’s not done at your age.” With her family falling apart, Jean’s longing builds. This desire, coupled with a complete lack of boundaries (in her household and neighborhood alike), opens Jean up to potential dangers.

Jean starts hanging out with Fender Steelhead, a troubled neighborhood boy. Rumor has it that Fender and his brothers torture and kill dogs (possibly even a pony) in their basement, but to Jean this only adds to the intrigue. She’s disappointed to find that the Steelhead home is not as wild or ramshackle as she’s heard. There’s no sign of Fender’s parents, but there’s an overstuffed recliner and a braided rug, an open floor plan with a lot of light. Jean notes that “Somebody’d had money once. Somebody’d once proposed trying her hand at familial structure.” Fender turns out to be his own untouchable combination—he invites Jean to sit on his bed, but instead of making a move he thumbs through a stack of baseball cards, reading the names of the players aloud. Jean fingers his cotton sheets, confused to find “the boy who smoked cigarettes on the playground still sleeping between spaceships and stars.”

Frustrated with Fender, Jean shifts her attention to her elderly neighbor, Otto Houser, a man with a wheelchair-bound wife and an aging, mentally disabled son. Otto is the first person to shamelessly acknowledge Jean as a sexual being. He sits in his house across the street and watches her play the piano (in her bathing suit, as always). Even at a distance, Jean notices Otto’s response to the “forward thrust in [her] body…the thin waft of one of [her] arms eagled-out as it ran up and down an octave.”

Everyone in Otto’s house is “facing death ass-first to the wind” and that’s a dark pull for Jean. Otto’s wife—Jean calls her “His Helene”—could die at any moment. “What water His Helene had left in her had congregated in her feet. … The doctor said next it would move to her heart. That’s what would take her. That one big rush of her own stream.” In an intensely uncomfortable scene, Otto shows Jean the intimate ways he now must care for his wife’s ailing body. But Jean is unfazed; she tries “to be rough” with His Helene, to “remind her she [is] still a woman.” This is one of the many ways DeWitt masterfully imbues Jean with authority. As the relationship between Jean and Otto becomes more and more disturbing, Jean’s agency is ever present. Though she is not yet a teenager, the choices she’s making, no matter how unseemly, are of her own volition. There’s a cool confidence in Jean; she knows more about the world than she should, as she’s spent years bearing careful witness to the permissive adults around her.

Like Jean herself, the language in White Nights radiates heat. Household objects are eroticized and described using the language of the body. Garbage bags and bathtubs have open mouths. A smoldering fire pit “smell[s] like whoring.” At the same time, DeWitt’s masterful swerve makes the domestic surprising: a defrosting chicken is “a bird… shed[ding] its ice.” Strips of flypaper dangle like “rows of gristle” and a kitchen is “the gut of … loneliness.” DeWitt often shuns naturalistic dialogue in favor of style; characters have their “rot on” and their “tail up.” When Birdie gets a little too hyper, a babysitter, her fingernails wet with polish says, “Easy there, Little Wonder. …You’ll upset my color.” This choice may be jarring for some readers, but for me it’s merely an extension of DeWitt’s syntactic daring.

White Nights ends, like its epigraph, with a transformative event. What happens feels inevitable—the pressure has been mounting since the first pages—but what’s surprising is DeWitt’s approach to the fallout. Rather than walking us predictably through the tragedy, she turns instead toward its odd beauty. We’ve known all along the blinding light would come, the brilliant flash that will irrevocably change Jean, her family, her small town. It was never a matter of if the atom would split, but when.

Kimberly King Parsons is a writer and editor based in New York City.