In 2016, the last manufacturer of VCRs, the Funai Corporation, announced it was halting production. Analog holdouts looking to replace their players were finally out of luck. While the obsolescence of VHS may seem like a technological footnote, it also represents a tangible cultural loss. When the Yale University Library acquired roughly 2,700 horror and exploitation films from 1970s and '80s on VHS tape, the librarian, David Gary, explained that the movies revealed the "cultural id of an era." Now that VHS has become a relic, it has also become fodder for cheap thrills and shared nightmares: Many films of the last twenty years, from The Ring to The Blair Witch Project, have portrayed the horrors you might stumble across on an abandoned videotape. As the media theorist Caetlin Benson-Allott puts it, the appearance of "videocassettes in motion pictures tend to bring with them a host of cultural anxieties about technology, reproduction, and mortality." It is not just the scary movie that horrifies us: The medium itself conjures our collective anxieties.

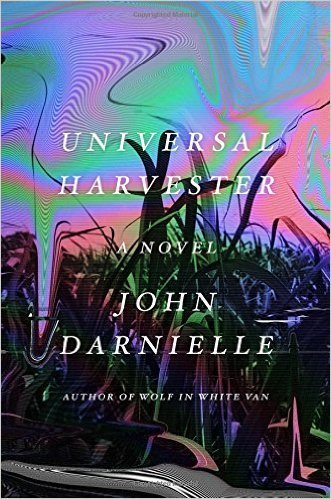

John Darnielle's new novel, Universal Harvester, taps into this potent mix of apprehension and nostalgia. Set in Nevada, Iowa, in the late 1990s, the story is about a collection of eerily modified tapes that set the employees and patrons of the rural town's "Video Hut" on a death-obsessed mystery. On one seemingly insignificant day, a customer tells one of the Hut's clerks, Jeremy Heldt—a twenty-two-year-old marooned in Nevada—that the store's copy of Peter Bogdanovich's Targets has an odd interruption. A few days later, a woman returns a copy of She's All That with a similar issue. Now convinced to investigate, Jeremy is unsettled to see a brief bit of grainy footage spliced into the middle of Targets that shows a hooded woman making gawky, choreographed movements in a dilapidated building. Baffled, he tells his boss, Sarah Jane, who becomes absorbed in the mystery when she realizes that the movies were shot near her childhood home. Jeremy is soon dragged into the quest, a slippery adventure in a sleepy town.

Darnielle ties together the setting, the mystery, and the plot by employing film clichés, always presented with a kind of wink to the reader. When Jeremy decides to investigate the tapes instead of finally escaping town, the story's anonymous narrator makes the obvious cinematic comparison:

"In Hollywood, these moments sometimes present themselves as a crossroads in a cautionary tale, where the hero comes to think of himself as having been rescued in that one moment, from the grinding boredom of an unvarying daily regimen of unglamorous tasks. Fate steps in, or chance, or providence, and reveals his purpose, his calling, the shining vistas and curious byroads of his destiny. . . . But this isn't Hollywood."

The book relies on movie tropes as often as novelistic ones—you can picture even the smallest moment as an unfolding montage, like when Darnielle compares the sight of cornfields through a speeding car's window to "stock footage." The midwestern town he's crafted, and its panoramic pastoral landscape, seems wooden and slightly overlit, like an old-fashioned film set.

Darnielle writes evocatively about everyday objects, vividly marking subtle shifts in technology and culture. For example, when talking about early cell phones, he invokes our own age as he gently mocks the past: "In the future, cell phones like the one Sarah Jane handed Jeremy would be referred to as 'burners': cheap phones, often purchased without a contract at a department store, to be used for a very short period of time and then thrown away." Like Don DeLillo, Darnielle is able to precisely describe the character of an object in the world. When talking about the farmhouse a character sees from the road (in a winking nod to DeLillo's White Noise), Darnielle beautifully describes how these homes are both "timeless and impermanent without ever committing to either side." That description is a succinct statement of the novel's ostensible aim: to conjure a bygone era that can defy time. But the readers know the town's fate—the obsolescence of its way of life, its labor, its sources of entertainment—as surely as they know what will happen to any horror-film heroine. Darnielle holds the inevitable at bay for much of the novel, while also acknowledging that there is something perverse—perhaps even sinister—in doing so.

One of the novel's disappointments is that Darnielle never manages to convincingly conjure the giddy excitement of this era's VHS B movies, a lapse that is particularly galling when he describes the mystery footage at the heart of the novel. In the end, the book's driving evil is annoyingly vague: The tapes have something to do with a missing mother and cults, but we never get to experience the cathartic fright that a scary flick elicits. A present-day coda offers the book's only truly jarring moment: As it happens, it involves an iPhone—surely our era's conduit for collective anxiety.

In the concluding section, Darnielle introduces a new set of characters—a California couple and their college-aged children who move to Iowa in the present day. The kids discover the tapes and attempt to solve the mystery with some digital sleuthing. When they find out that the original participants, like Jeremy, are no longer interested in the tapes, the mystery, or the town of Nevada, you might expect Darnielle to close the novel with an elegy for a lost way of life. Instead, we get a sober declaration: He asks us to imagine that no time or place is prelapsarian, no era ever even slightly golden.

Kevin Lozano is a writer living in Brooklyn.