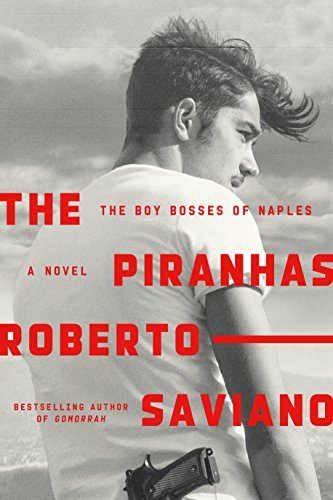

In English, “novel” equals “fiction”—the meaning is unambiguous. In Italian, however, it’s a bit more complicated. The word romanzo describes a book-length prose narrative, but it does not distinguish between fact and fiction. In the work of Roberto Saviano—Italy’s most famous living writer save fellow Neapolitan Elena Ferrante—they regularly bleed together. Since 2007, when Saviano’s first book, Gomorrah, was translated into English, US readers have had difficulty navigating this ambiguity. Categorized as a romanzo in Italy, Gomorrah was presented as a work of “investigative writing” by its US publisher, Farrar, Straus and Giroux—a phrase New York Times reviewer Rachel Donadio observed “suggests careful lawyering.”

That “careful lawyering” may be why Saviano’s newest book The Piranhas is being billed as Saviano’s third romanzo but first ever novel. “The characters and events that appear here are imaginary,” Saviano writes in an author’s note. Still, he cannot resist the allure of real life. “What is authentic, on the other hand, is the social and environmental reality that produces them.” The Piranhas will sit on different shelf in libraries and bookstores than his previous work, but it shares this essential uncertainty: What is true? What isn’t? Although the question of fact versus fiction can seem like a tired one, Piranhas offers a twist: The real world that the novel is based on was shaped by none other than Saviano himself. His vivid 2007 romanzo, Gomorrah, which detailed the Camorra crime syndicate, has cast a long shadow in Naples. In 2014 the bestseller expanded its audience by orders of magnitude with a TV show that has become the most popular scripted show in Italy, where it’s ratings rivals even soccer championships. Saviano’s book is clearly anti-Camorra—there’s a reason why he still receives death threats—but stories about the mafia also invariably glamorize it. Power and violence are inherently interesting.

In real life, a young man in Naples named Emanuele Sibillo loved to watch episodes of Gomorrah every week with his girlfriend. Until his murder at age nineteen, in a narrow street in central Naples in 2015, he led a group of young people in a violent takeover of the center city’s drug markets. He was a keen student of media and cultural narratives—so much so that he modeled his long beard on images he’d seen of ISIS fighters. The media dubbed Sibillo’s crew of adolescents “la paranza dei bambini”—the children’s gang.

Saviano first published The Piranhas, about a media- and mob-obsessed Neapolitan teen who starts his own gang, in 2016, one year after Sibillo’s death. Its main character, Nicolas Fiorillo, is much like Sibillo, though he is light-haired where his real-life counterpart is dark. In 2017, Gomorrah introduced a new character to its third season, “Sangue Blu,” modeled in part after Sibillo—but blonde, like Nicolas. The same year, Saviano published a sequel to The Piranhas, Bacio Feroce (Fierce Kiss), that follows Nicolas after his paranza is established (and which has yet to be translated into English). In 2018, Sky Italia—the same television network that makes Gomorrah—aired a documentary, ES17, about Sibillo’s life and credits Roberto Saviano for the idea.

It’s an ouroboros of narrative: reality informing story and story informing reality. The world of The Piranhas is similarly intertextual. The young people of Forcella, the tiny Naples neighborhood where the book is set, speak in cultural signifiers divorced from their original context. Nicolas Fiorillo, called “o Maraja” by his friends and fellow paranza members, worships Mussolini, Che, and “the most vicious kind” of American hip-hop without caring about their individual ideologies. For him, they are avatars of masculinity and violence in a world he sees as defined by both. For his first murder—“a piece of work” in the parlance of Naples’s criminal underworld—Nicolas dons a costume of Breaking Bad’s Walter White that he bought on Amazon. Trying out a vintage semi-automatic weapon, Nicolas assumes a pose he’s learned from the movies. “Ua’ guagliu’,” he calls to his friends. “Chris Kyle. I’m Chris Kyle.”

“Ua’, seriously though, Maraja,” they answer, “you really are the American Sniper.”

Nicolas calculates, Nicolas inflicts, Nicolas kills. Readers are meant to admire this clever, handsome boy who quotes Machiavelli off the top of his head. “Just and unjust, good and bad. They’re all the same,” he contemplates early in the novel. (The Piranhas often slips into a close third person perspective.) “On his Facebook wall Nicolas had lined them up: the Duce shouting out a window, the king of the Gauls bowing down to Caesar, Muhammad Ali barking at his adversary flat on his back. The strong and the weak. That’s the only real distinction. And Nicolas knew which side he was on.” Power is Saviano—and Nicolas’s—primary interest: raw, violent, merciless. Perhaps Bacio Feroce, or the following novel (Saviano has planned a trilogy), will show the limits of this, or any, power. But The Piranhas is intoxicated with it. When a subordinate takes a gun from the paranza’s cache without asking, Nicolas sets a uniquely degrading punishment: the offender’s older sister must perform oral sex on every member of the group, in front of the group. The cost of misbehaving is at once relatively low (it is, on balance, bloodless) and impossibly high. It’s an expression of Nicolas’s canny understanding of how power may be wielded.

He ultimately pays a high price for his ambitions, but it’s a moment that also coincides with the paranza’s greatest triumph. Though explicitly ironic, the juxtaposition still feels empty. Saviano gestures towards the teenager’s pain but never makes us feel it. Readers are as isolated from normal human experience as a sociopath might be, and, perhaps, as Nicolas is.

Molly McArdle is a writer in New York.