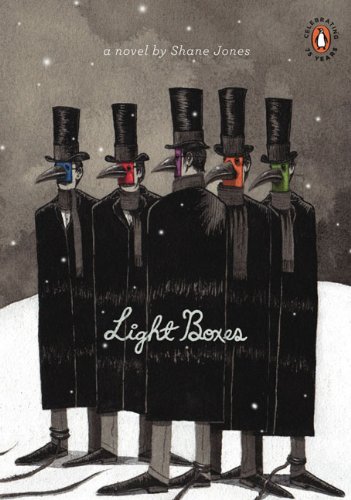

The striking cover image of Shane Jones’s first novel, Light Boxes, is both playful and foreboding, an apt rendering of the novel’s offbeat charm. It reads like a twisted fairy tale. The story follows Thaddeus Lowe, who lives with his wife, Selah, and daughter, Bianca, in an unknown era, in an unnamed town where it is always February, presided over by a godlike character—also named February—who is responsible for the soul-crushing cold and darkness. He’s powerful and mysterious and orders “the end of all things that could fly,” a particularly harsh measure for townspeople who escape the gloom by flying in hot-air balloons. Under his command, menacing priests descend on the local library, where they confiscate textbooks and tear out all the “pages about birds, flying machines, Zeppelins, witches on brooms, balloons, kites, winged mythical creatures.”

They post February’s demands on trees around town, such as “no one living in the town should speak of flight ever again.” To make matters worse, snow falls continuously, there is no sunlight, and children, including Bianca, begin to vanish. Led by Thaddeus and a collective of bird-masked former balloonists known as the Solution, the townspeople revolt against February. All their tactics fail—including hoisting “weather-changing poles” to destroy the clouds that obscure the sun. The struggle against February is communal, but Thaddeus is tormented by particularly grievous losses: “Tell me everything won’t end in death,” he reflects in a moment of despair, “that everything doesn’t end with February. Dead wildflowers wrapped around a crying baby’s throat.” After losing those closest to him, Thaddeus feels as though the battle is “a terrible war against me.” He stops speaking for a while and starts to see ghosts.

The otherworldly narrative is complemented by an equally imaginative design, with Jones employing an array of fonts, formats, and typefaces to express the peculiarity of his story: a name at the top of the page to indicate which character is speaking, or a phrase set in boldface as the lead-in to a section. Some pages are almost entirely white space, evoking the snow that blankets the town, while other pages have only a single line, for instance, “I vomit ice cubes.” (That’s Thaddeus in one of his most tormented moments.)

There are mantras, chants, and lists throughout, including one of “Artists Who Created Fantasy Worlds to Try and Cure Bouts of Sadness,” such as Italo Calvino, David Foster Wallace, and Anne Sexton. The character February may seem brutal and relentless, but he’s not exactly evil. “I want to be a good person,” he reflects, “but I’m not.” He often cries and hasn’t gotten a haircut in more than six months. He’s clearly in need of psychoanalysis, and a weekend in South Beach might not hurt, either.

Light Boxes is absurd, cryptic, and often bizarre, but if you’re willing to roll with it, all is made clear by the end (and is quite satisfying). There are also marvelous sentences throughout: “Thaddeus looked up and saw the owls on a branch. He asked them if they had seen the three children. Owls can’t speak, and Thaddeus felt foolish.” The novel gradually begins to resonate on an emotional level as well, and though the book might be labeled, and perhaps dismissed, as experimental or gimmicky, Jones is as fussy about his story as he is about the typography and design. The eccentric format and metafictional elements serve a purpose; when Jones shifts to a tiny font, for instance, he effectively conveys a child’s frightened, insistent whisper. He also handles imagery like a gifted poet: “Last night everyone in town dreamed the clouds fell apart like wet paper in their hands,” and “the sky flutters like a flag, and then it goes black like closed curtains of wool.” The pervasive sadness in the town “sounds like bubbles blowing slowly in stream water.”

It is fitting that such a wonderfully quirky novel has an intriguing backstory: The book was first published in 2009, by Publishing Genius Press—a one-man operation in Baltimore—and, despite a print run of only six hundred copies, became a hit. After Spike Jonze purchased the film rights, Penguin picked it up, publishing the novel essentially as a debut.

Light Boxes can be read as an allegory about the creative process—imagination unable to take flight—or as a cautionary tale about seasonal affective disorder (the townspeople take to wearing light boxes on their heads to simulate sunlight, not unlike the light therapy that SAD patients undertake). Either way, Light Boxes is an enchanting and witty fable. This little book is not for everyone—but that, of course, is one of its virtues.

Carmela Ciuraru is the editor of several anthologies and is writing a book about pseudonyms for HarperCollins.