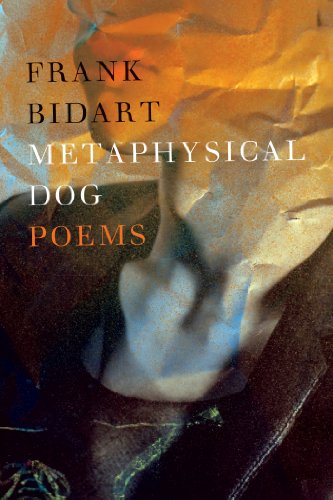

Metaphysical Dog, Frank Bidart’s latest book of poetry, begins with a poem, also called “Metaphysical Dog,” that glimpses the eponymous dog doing what dogs do, namely rolling on its back, “butt on couch and front legs straddling / space to rest on an ottoman.” This impression of listlessness is interrupted by a severe voice (seemingly of the poet):

How dare being

give him this body.

Held up to a mirror, he writhed.

Believe it or not, this is the beginning of a collection of poems about how we love. Bidart’s scope is ambitious, addressing sexuality, sex and desire, patriotism, admiration (see “Poem Ending with a Sentence by Heath Ledger”), filial love, romantic love, and the love we feel in grief. The poet is interested in how these expressions of love are literally manifested in and dependent on the medium of the body, which is primarily concerned with physical and not emotional survival. In other words, how do we reconcile the divergent needs of the mind and the body while still understanding that they are inseparable except through death? Colloquially, this is sometimes called “the mind-body problem.”

Throughout Bidart’s career, he has been fixated on this natural and yet confounding schism. Bidart’s well-known early poem “Ellen West” is based on a case study of a woman with anorexia who is obsessed with perfection and the idea of “having to have a body.” She decides that if she must have a body, then it should be “the image of her soul,” which of course is her undoing. The second poem of Metaphysical Dog is “Writing ‘Ellen West,’” and in it Bidart explains that “Frank” wrote the poem in a suicidal depression after the death of his mother and that the poem was a way of exorcising Frank’s grief and consigning it to the body of another:

must be lifted and placed elsewhere

must not remain in the mind alone

This other body is the body of Ellen West, self-identified as “meat,” but it is also that of poetry, made up of words, words that in a later poem Bidart tells us are “flesh.”

Though Metaphysical Dog is not written in the same narrative style as “Ellen West” and “Writing ‘Ellen West,’” the impression of her body—her flesh—figures prominently in the poems and engenders a narrative tone that relies less on plot points than on the formation and birth of the whole, composite being that is Bidart’s poetry. This body of poetry is rendered through the repeated use of images related to physicality—breath, flesh, hunger, chimera—to create a deepening and increasingly vivid understanding of what might be better termed “the mind-body connection.” While in lesser poetry the frequent repetition of certain images, themes, and phrases might become boring and vacuous, Bidart avoids this pitfall by writing in a conversational, if not sometimes churlish tone that showcases the enviable originality of his wit. The overwhelming impression is that of a poetic ecosystem where each poem feeds into the next, and the larger poetic body steadily accrues meaning. This is not the type of collection where one gets the sense that the poet wrote fifty different poems and then set about organizing them for publication—there is an order and an escalation to Metaphysical Dog that makes the poems, especially the ones that appear later in the book, feel strong and viable.

One such poem is “As You Crave Soul,” the one in which Bidart proclaims, “words are flesh.” The poem is ostensibly about trying and failing to write poetry:

To carve the body of the world

and out of flesh make flesh

obdurate as stone.

Like Ellen West, who cannot function in life because she is chronically dissatisfied with her body, here too writer’s block is conveyed through the inability of a person to mold the body to fit his perception of the external world. Bidart’s metaphors are impressive in isolation, but his brilliance in Metaphysical Dog lies in his talent for seamlessly layering or modulating chosen motifs so that his poems resonate on multiple levels. In “As You Crave Soul,” the writer’s frustration becomes the lover’s frustration, also a frustration of the flesh:

You mourn not

what is not, but what never could have been.

What could not ever find a body

because what you wanted, he

wanted but did not want.

Ordinary divided unsimple heart.

By casting and then recasting the mind-body problem as the root cause of failed creative endeavors and then failed relationships, Bidart initiates a democratic conversation that approaches this highly philosophical conundrum with metaphysics tempered by experience and intellect augmented by sentiment. Loftiness and pedagogical import are entirely absent from this conversation, making for poetry that is deeply personal, vigorously intellectual, and remarkably unsimple.

Isabelle Dienstag is a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.