I first encountered Alexander Theroux’s writing—the style of which is grandiloquently lyrical, dizzyingly erudite, and often acerbic—through his books on colors: taxonomies of the spectrum we think we’ve seen but that Theroux, attentive observer that he is, suggests we haven’t really seen at all. I followed up these readings with savoring every word of three of his novels, beginning with Darconville’s Cat, his second novel, a book that satisfies syntactically, texturally, and structurally, reminding me at once of Henry James (because of the novel’s sentential convolutions and its paragraphic architectonics, and also because of the way it limns various consciousnesses); Virginia Woolf and Wallace Stevens (because of its luxuriant and daunting yet still inviting lexicon); John Hawkes (because of its lyricism and sensuousness); William Gaddis (because of its range and the way it captures different voices); Mark Twain (because of its scathing wit); and contemporary fellow travelers like William Gass and Mary Caponegro (hooray for longeurs, digressions, and taxonomies!). What is perhaps more important is how little I actually thought about these things while reading the novel, how, ultimately, the novel coheres into a wonderful prose object, unique in its own right: a singularity. Three Wogs, Theroux’s triptych of linked novellas, is an outrageous book brimming with bigots and other grotesques, all virtuosically rendered, which coheres into a comical critique of human stupidity. An Adultery is largely devoid of lexical pyrotechnics, but it is no less lyrical, and its unwavering scrutiny of emotional brutalities is unparalleled. The narrator’s self-absorption often leads him to observations that are at once insightful and imperfect:

"A lover is never a completely self-reliant person viewing the world through his own eyes, but a hostage to a certain delusion. He becomes a perjurer, all his thoughts and emotions being directed with reference, not to an accurate and just appraisal of the real world but rather to the safety and exaltation of his loved one, and the madness with which he pursues her, transmogrifying his attention, blinds him like a victim."

While unafraid to examine duplicities, unfairness, and meanness, and to lacerate the perpetrators of same, Theroux in his novels also reflects on beauty, fairness, and love.

In Enemies of Promise, Cyril Connolly describes the Mandarin style as the

"richest and most complex expression of the English language. It is the diction of Donne, Browne, Addison, Johnson, Gibbon, De Quincey, Landor, Carlyle and Ruskin as opposed to that of Bunyan, Dryden, Locke, Defoe, Cowper, Cobbett, Hazlitt, Southey, and Newman. It is characterized by long sentences with many dependent clauses, by the use of the subjunctive and conditional, by exclamations and interjections, quotations, allusions, metaphors, long images, Latin terminology, subtlety and conceits."

All of these stylistics attributes and more may be found in Theroux’s writing, a vast bibliography which also includes poetry, fables, criticism, newspaper stories, and, most recently, The Strange Case of Edward Gorey, a smart, engaging, and insightful monograph asking as many questions about the quirky artist as attempts at answers. For a writer like Theroux this is hardly surprising, as he is one of the last of the Mandarins, a dying breed.

Bookforum: There’s a musical structure, fugal, in fact, to your monograph on Edward Gorey, where motifs and themes are introduced, repeated, sometimes effusively elaborated on. Was there something about Gorey or his work, or both, that suggested this approach? What model or models, if any, directly or indirectly, did you draw on for inspiration? Who are some of your favorite essayists? What do you like about them?

Theroux: Edward Gorey was very ornate—Corinthian!—in his love of language, and when he was in a chatty mood his conversation, crackling with allusions, was rich and often rare, exaggerated, campy to a degree, invariably tinctured with lots of movie-love, sarcasm, irony. Mind you, it was not that the man was trying to be something, contriving, say, to appear a cavalcade of wit, merely that, rather like Dr. Samuel Johnson, he happened to have sharp, remarkable “views” on all sorts of subjects, almost all worthy of note.

Gorey was the sole model for my book on him, but I often thought about Ronald Firbank, Harold Acton, Paul Lynde.

As to essayists, among my favorites have been William Hazlitt, Henry James, Waldo Emerson and H.D. Thoreau, of course, Walter Pater, George Orwell, Flannery O’Connor, Fernando Pessoa, and Guy Davenport.

Bookforum: According to William Gass, in his essay “I’ve Got a Little List,” lists “suppress the verb and tend to constantly remind us of their subject;” a list “is the fundamental rhetorical form for creating a sense of abundance, overflow, excess.” Gass continues in this essay— as much a marvelously maddening collection of lists as it is a meditation on the proliferation of lists—to explore the list’s philosophy, its psychology, our “obsess[ion] with hierarchies in the form of lists,” about how “popular software programs known as “list servers,” which manage electronic mailing lists and document their distribution over the Internet…can make a mouthful of mush.” Lists are “juxtapositions, and exhibit many of the qualities of collage. The names which appear on them lack their normal syntactical companions. Most lists are terse, minimal, bald; they are reminders, commands, aspirations.” In short, it’s an essay that from start to finish simply asks you to take note. “Listing is a fundamental literary strategy,” Gass observes. “It occurs constantly, and only occasionally draws attention to itself.”

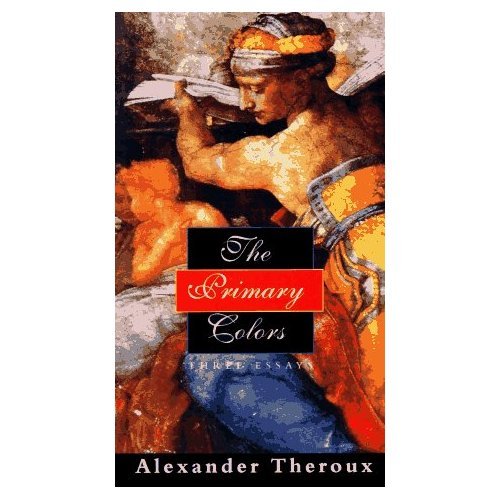

Besides Gass, I can’t think of any other contemporary writer who uses lists as evocatively as you do. Like your essay collections on colors, The Primary Colors: Three Essays and The Secondary Colors: Three Essays, The Strange Case of Edward Gorey is full of inventories: of Gorey’s favorite films, music, and books. Would you talk about list-making, and why you make so many of them? Also, would you list your essential films, music, and books? Dishes? Drinks? Paintings? Sculptures?

Theroux: Lists, of course, comprise the beating heart of the “encyclopedic” novel— consider M. Cervantes, F. Rabelais, L. Sterne, J. Joyce. They frame categories, for one thing. It is invariably a vehicle for serious knowledge. (Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy is a good example.) The literary strategy Gass writes of touches on the cumulative, the aggregate, the incorporative. The “Ithaca” chapter in Ulysses, the rigidly organized catechism, was reportedly Joyce's favorite episode in the novel. The style is that of a scientific inquiry, with questions furthering the narrative. The deep descriptions range from questions of astronomy to the trajectory of urination. Oddly, there is also an intrinsic humor to lists. Remember how funny it was on the old Jack Benny Show to hear the train depot announcer solemnly intone, “Train leaving on Track Five for Anaheim, Azusa, and Cu-ca-monga”? Summation is by definition a putting together of things. But what could be more revealing of a person, a movie star, say—no essays, please—than a simple list of his or her “likes” and “dislikes”? I would cite perhaps food aversions, which shed great light on a person, but then they would come under “dislikes,” no?

Scholars are list-makers, I feel. Who would deny that inventories are also the sine qua non of compulsive crackpots?

Bookforum: In The Strange Case of Edward Gorey, you relate a favorite story of George Bernard Shaw’s wherein a newly coronated Queen Victoria considers what she will do with “her new powers,” deciding that, for her, “there was nothing more delightful than an hour of solitary confinement.” You follow the anecdote by positing that it “is not something many understand today, when technology has cut badly into the meditative.” What forms of technology were you referring to and what do you mean by “the meditative”? Would you describe the ways in which technology, as you understand it, has “cut badly into the meditative”? How can one protect “the meditative,” shield him- or herself from ever-encroaching technologies?

Theroux: I still believe that the sound of a telephone ringing is, alone, one of the worse sounds on earth. Grating! What does it say of me that I interpret that as being summoned, and should I therefore go into psychoanalysis? “We are eager to tunnel under the Atlantic and bring the Old World some weeks nearer to the New;” wrote Thoreau with a good deal of prescience, “but perchance the first news that will leak through into the broad, flapping American ear will be that the Princess Adelaide has the whooping cough.” Consider all the thumbfumbling with cell phones nowadays—what are people saying to one another every five minutes that is so important?—machines that can compute, take pictures, deliver mail, bring you news, and for all I know act as pop-up toasters. Texting, tweeting, I can’t even bear the words. Ponder as well the grim effect alone on language!

Trappists understand conversation to be at loggerheads with meditation, and of course they’re correct. It is healthy to work in silence, be contemplative, ponder one’s inner spirit. Thomas á Kempis’s remark may seem a bit severe—“Every time I go out among men, I come back less a man”—but, at least for me, it speaks to a kind of serenity being lost today in daily avalanches of wasteful blather and blabber. I would say that the best way to protect the meditative, as you put it, would be to try to watch for the pitfalls of technology as a time-suck and to learn to value and find beauty in creative silence.

Bookforum: You describe Gorey as someone who read “everything, outré things like the works of Oliver Onions, the poet James Very, Mrs. Oliphant—remote English novels from the 1880s like Adam Graeme or He That Will Not When He May—and people like Capt. Marryat, George Farquhar, E.C. Benson.”

Reading your books, I get the sense that you’re a reader who reads across genres, disciplines, histories. How would you characterize yourself as a reader? What books might someone be surprised to hear that you’ve read?

Later in your monograph, you say that Gorey didn’t like to travel and that it “was by reading alone that he traveled and kept him abreast of the waking world.”

What about you? Do you like to travel? How do you keep “abreast of the waking world”?

Theroux: I feel obliged to know and certainly treasure knowing. I read so as to develop my thoughts and of course travel to open what Descartes called “the great Book of the World.” I would characterize myself as a wide and willing reader, open to all genres and all subjects and all good authors—from Raymond Nonnatus to Raymond Chandler to Raymond Bradbury—and pretty much most subjects, excluding books on apes, drag-racing, Judaica, stocks and bonds, fishing guides, self-help books, crapulous novels, all political autobiographies and memoirs, of course, and anything on Indian (as in New Delhi) philosophy. (I thought I’d give you a list.) I think people might be surprised to hear I like graphic novels, cookbooks.

As to traveling, my book, Estonia: A Ramble Through the Periphery, was published in October, 2011. I would love to get writing assignments that would take me to Egypt, Syria, Lebanon.

Bookforum: In The Strange Case of Edward Gorey, you write: "I have noticed that those the press, the people, the planet ignores tend to be its most profound inhabitants, and that, sadly, those taken up, pampered, and praised are mainly hustlers, churls, opportunists."

Who are some of those “profound inhabitants” who have been ignored? Who are some of the “hustlers, churls, opportunists”?

Theroux: Actors and actresses, almost to a one pampered and praised, are some of the hustlers, churls, opportunists to whom I refer, along with political pundits. Partiality, preferential treatment is the rule of advancement everywhere. Connections ‘R’ Us!

Nepotism in the world of the American press, sports-casting, television, and the film-world is shameless and grotesque. Anderson Cooper is Gloria Vanderbilt’s son. Gwyneth Paltrow is Blythe Danner’s daughter. Chris Wallace is Mike Wallace’s son. Kate Hudson is Goldie Hahn’s daughter. This list is endless. Sarah Palin has turned her having been a VP nominee into a full-time family career. It was always the children of political hacks who got tickets to sit in the front row to see the Beatles and who got to visit them back- stage, boring the Fab Four rigid. I look at the utter mediocrities in Congress and cannot fathom that we depend on them. Dillweeds, to a one, the dumbest bastards in the country being interviewed about economics!

In the profound inhabitants department, I would put so many great writers. Simone Weil, Baron Corvo, James Purdy. How many Americans know who Wallace Stevens is? Ned Rorem has never been recognized for his profound opinions. It would never have occurred to anyone to ask Edward Gorey to go on Johnny Carson, but how many times did James Coco appear?

Bookforum: In The Strange Case of Edward Gorey, you write: "Just as all truly good writing is an assault on cliché, an individual truly to live, to be himself—to “selve,” in the words of Fr. Gerard Manley Hopkins—must avoid stereotype at all costs, to flee the predictable, the conventional, the habitual, and to seek and find one’s original self, to discover one’s original meaning.

So, why do you say that “all truly good writing is an assault on cliché”? And, how would you define one’s “original self” and one’s “original meaning”?

Theroux: There is an original self in everyone, often sadly lost as the years go by. How many unique people are there on any given bus-load of people? I would say many—

potential inventors, painters, sculptors, farmers, writers, explorers—but time, habit, fears, diffidence, circumstances of all sorts, illness, lack of funds, indeed, even indifference, sloth, bad choices, have covered any potentialities like a fine dust, so that in the end they are lost. Gone is the “thisness” of that person, the unique and miraculous haeccitas: potency never become act. Just as a person who does not drink can ever know whether he or she is an alcoholic, the unplumbed self, if never examined, never sought, never tried out, will ever be known.

Bookforum: Arriving to someone’s home for a party or whatever, I will, often enough, after getting pleasantries out of the way, go directly to his or her library and browse. For me, it gives me a sense of what that person is like, more than any amount of chitchat, at any rate, which usually happens at such affairs. More and more, I’m discovering that if there is a library, it’s probably full of DVDs and a few technical manuals and whatnot. Maybe a couple of books. So, is a physical library full of tangible objects called books important to you? What does your personal library look like?

Theroux: I was at one time many years ago writing pieces for the San Diego Reader, a joyless experience I took up because I needed the money, and living a month a year in tidy, affluent, Coronado I would occasionally have the occasion to use the local library there. One day I needed to check something in Virgil’s Aeneid. I couldn’t find the book anywhere and inquired about it. They had no copy! But there were entire walls of VHS tapes and DVDs, aisles of brainless movies on vampires, robots, transformer monsters, and teenage sexploitation films.

My personal library is so extensive that I can’t find anything either. There must be a parable there somewhere.

Bookforum: What are your thoughts about books as physical objects? What are your thoughts about electronic readers?

Theroux: Electronic books seem logical and useful. What you don’t have is the artifact. I collect 45 rpm records. Years ago an acquaintance of mine pointed out that one could find on the Internet any song one wanted to hear. I held up a vinyl copy of “Someone Up There” by Little Nate and the Chryslers and said, “Find that.” I picked up the Globetrotters’ “Rainy Day Bells.” Or that.” I grabbed “Don’t Say She’s Gone” by the Shortcuts. “Not on the Internet.”

Bookforum: Your love for Wallace Stevens, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and E. M. Cioran (these are three of my favorite writers) is evident throughout The Strange Case of Edward Gorey. Would you talk about how you came to discover their work and what about you enjoy about it and have learned from it?

Theroux: My fascination for Emil Cioran, grew out of my early interests in the Russian novel, and reading his brilliant observations on the modern themes of alienation, absurdity, boredom, futility, decay, the tyranny of history, the vulgarities of change, awareness as agony, reason as disease, as William Gass lists them, are an anodyne to the stupidities and extremes of the modern world, a catharsis in the Aristotelian sense to stave off its many infections.

I wrote a term paper on Gerard Manley Hopkins as a college freshman. Never had language appeared quite that way to me before. It all seemed as much music as words. I was also impressed that Hopkins had been a priest—and a Victorian. The words, the lines, of all of his lyrics seemed inevitable, always a sure sign of great writing, and one recited them the way one whistled Mozart—they were “pied,” like all beauty. “As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw flame; / As tumbled over rim in roundy wells / Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung bell’s / Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its name..."

As to Wallace Stevens, we read “Anecdote of the Jar” in high school, and I never forgot it, intrigued as I was by the many ways that small poem could be interpreted. Stevens is far and away my favorite American poet, much as I love Dickinson and Whitman. Any bookshelf missing his Collected Poems is vitaminless. His bravado, his daring use of language, his bravado, his Christmas bulbs of wit and wayward words has infected my own poetry. Here is one of mine:

A Poule At Pavillon

At Pavillon, that shiny poule

indelicately swirling a fork among tiny crevettes

knows rouged shrimp from the shapes

of pointed pain that paid for them.

Her mahogany red nails, as flash and sharp as tines,

are really black as night.

What clacking from that table!

Plates, nails, forks, shells, tongs, the shaking

of jewels by her swirling shine.

Color characterizes a state of mind

in whatever women wearing white batiste and gold

with shaping shears for fingers

as it also does the noise she makes

working those intractable crevettes around in all

the rouge they need for taste,

her shine, that noise, inviting

the disapproving look of three quiet hateful ladies

at a nearby table at Pavillon,

exchanging looks in total silence

as sharp and flash as tines that say they well know

rouged shapes from silly shrimp.

Bookforum: You say that Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood was a book that you and Gorey “both greatly admired”? What did you and Gorey like about it?

Theroux: Phrases from it. Lines. “A hoofed raised in the economy of fear.” “When she fell in love it was with a perfect fury of accumulated dishonesty; she became instantly a dealer in second-hand and therefore incalculable emotions…” “I have been loved by something strange, and it has forgotten me.” Nightwood is a masterpiece. Then there is the inimitable Dr. Matthew “Mighty Grain of Salt” O’Connor, the transvestite who pretends to be a doctor—full make-up, nightgown, woman’s wig—and the brilliant, hellacious central chapter in which he appears called “Watchman, What of the Night?” I was in touch with Miss Barnes in 1967 when I was a graduate student at the University of Virginia, hoping to write my PhD. dissertation on her and her books, who knew, maybe even a biography. We exchanged letters. She was living in Patchin Place, N.Y. She gave me names to contact, I followed up—Sir Samuel Hoare, Peggy Guggenheim, Marcel Duchamp—and they all replied, but I could never get all my ducks in a row. Barnes could be petulant, and the typeface of her letters when she wrote in high dudgeon were bitten into the very paper to the back! She was 75, living alone, ignored, grumpy, and slightly megalomaniacal. I was an amateur.

Bookforum: There’s a lot of discussion about reading, but very little about the value, the art of rereading? What’s the value of rereading? What do you think of Nabokov’s famous statements that “one cannot read a book; one can only reread it,” that a “good reader, a major reader, and active and creative reader is a rereader”? Barthes wrote: “Those who fail to reread are doomed to read the same story everywhere.” What do you personally get out of a first reading? How is a second reading different from a first? How do you determine for yourself what’s worth rereading? What are the gains and losses of rereading? What books have you reread, and why, and what did you get out of these rereadings?

Theroux: Owning books allows you to see them, behold them, so to speak, unlike electronic books. There is not a single book—or poem, or play—that I value that I haven’t re-read, I am certain. I am not sure Nabokov’s head was screwed on right when he made his gnomic remark, however, since a person can read a book once and find infinite value there. It goes without saying that further readings often add value and yield deeper truths. Nabokov was pathetically vain and a monster of hauteur, even though he was a genius. He would refer arrogantly in interviews to “my little Lolita,” but he stole both that name and theme from an original story called “Lolita” which appeared in a book of stories entitled The Accursed Gioconda that was written in 1916 by an obscure Berlin writer named Heinz von Lichberg (born Heinz von Eshwege in 1858), who was in fact a contemporary of Nabokov’s and lived in Berlin when Nabokov did. Maybe that was what Nabokov meant by “re-reading”!

Bookforum: Is it alarmist to say that enthusiasm for print literacy seems to be on the wane?

Theroux: No, I believe it is on the wane. But what isn’t? It is now virtually a crime reportable to the Thought Police to say, “Merry Christmas,” right? A grammar school in Seattle out of political correctness—I am not making this up—proceeded to dub Easter eggs “Spring spheres.” Hallowe’en in our secular age is now more suitably called the “Harvest Festival.” Chronologically gifted citizens have a difficult time understanding how this all came about.

Bookforum: In Enemies of Promise, Cyril Connolly describes Ronald Firbank as hating “vulgarity and vulgarity of writing as much as vulgarity of the heart. Indeed, the writers with the most exquisite choice of words, those who take obvious pains to avoid the outworn and the obvious, to achieve distinction of phrasing, are equally susceptible to the fine points of the human heart.”

Can one definitively make a correlation between a writer’s language and their vulnerability “to the fine points of the human heart”?

Theroux: W. H. Auden said that the trouble one had with one’s vocabulary represents the trouble one has with one’s self, or words to that effect. I believe that false and vulgar artless language in books constitutes a real kind of a fraud. When Firbank has a character say, “I adore finials,” he is daring to be original as a writer. Hack writers always rely on the same dull, gray images—why bother to reach? Most of the novels on the Best-Seller List in Fiction are a waste of trees. I cannot fathom how any writer can write a novel and put away style. Isn’t the alternative a kind of verbal Muzak? Clichés are like coins too long in circulation, flattened to the touch. I recently reviewed a novel by a popular novelist that had not an original or memorable sentence in the entire book. No, a writer’s language has everything to do with the human heart. It may be a real beating heart or a dumb boulder. Does anyone care? America’s best-selling beer tastes like warm piss.

Bookforum: In that same book, Connolly seeks to fuse the strengths of what he calls the mandarin and vernacular styles. What for you are the strengths and weaknesses of both styles? Is it important for a writer to fuse those two styles?

Theroux: A purely mandarin style needs vernacular variations, the way a boxer needs a variety of punches and a great pitcher needs a fast ball, a slider, a curve, and a change-up. Writing is a kind of show business, and one has to beguile, to intrigue, to shape a paragraph, a page, a passage. The great thing about the novel is that allows you do anything, go anywhere, you want. But that is also what can be terrifying about writing novels, its terrible freedom.

Bookforum: How would you define style?

Theroux: An identity assertion.

Bookforum: Would you talk about your writing process? What about revision?

Theroux: Writing is rewriting. This is not about spontaneous combustion. There are epiphanic moments, for sure, but no writer does not rework and rework. I read somewhere that Hemingway rewrote his seemingly simple, declarative novel, The Old Man and the Sea, 66 times.

Bookforum: Your thoughts on creative writing programs?

Theroux: They can homogenize weak and diffident souls. On the other hand. Flannery O’Connor was accepted into the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa where she first went to study journalism, and one of my ambitions when I first get to heaven—I will look for this nonpareil wandering among her peacocks—is to give her a big hug.

Bookforum: Would you talk about your stash of as-yet-unpublished manuscripts, like Black and White; The Grammar of Rock; Seacoast in Bohemia; Julia Chateauroux, the Girl With the Green Hair and Other Fables; Artists Who Kill and Other Essays; Anomalies; and your Complete Poems. Are you finished writing Herbert Head, Biography of a Poet? What about Becoming Amelia, your book on Amelia Earhart? Anything else in the works?

Theroux: I have all of these finished manuscripts in boxes right here. Where is a publisher with taste, or what is he waiting for?

John Madera's work has appeared in Conjunctions, The Believer, Opium Magazine, Salt Hill, American Book Review, The Review of Contemporary Fiction, Rain Taxi: Review of Books, and many other print and online outlets.