Let us see whether we can conjure up the representative readers, male and female, of pulp fiction. He is in his early forties and works as a traveling salesman—when he can get work, that is, for these are the Depression years. He wears a boxy blue suit, big black shoes with half-inch rims, a dubious tie the knot of which has not been fully undone in a long time, and a dusty brown fedora. He was born in Kansas but has moved many times. For now, he is settled in Biloxi, Mississippi, living in a frame house near the beach with a pizza waitress he met on the road somewhere outside Jackson on his way down here in the 1927 Studebaker that he bought years ago from a farmer in Stillwater, Oklahoma, who had gone bust. He has a job selling Fuller brushes door-to-door, and business is bad. He drinks too much cheap rye, spends too much time at the race track, and occasionally smacks his old lady around.

She wouldn’t think to buy a pulp magazine but sometimes will fill an empty hour after work with a copy of Black Mask or Gun Molls that he has left lying around the house. She is an Ohio girl, born in Akron longer ago than she cares to admit. She wears a print dress tightly cinched to show off her narrow waist, silk stockings the runs in which she mends with dabs of nail polish, and white shoes with clunky heels. She used to be a looker, but the years are showing now—too many late nights, too many hangovers, and the company of too many no-good men have etched deep furrows at the corners of her mouth and around her eyes. She is lonely in Biloxi and would like to go home sometime to see her mom and her little brother Titus, but Greyhound tickets cost money and old man Schwartz at the pizza place pays his waitresses peanuts. She dreams of California and its orange groves . . .

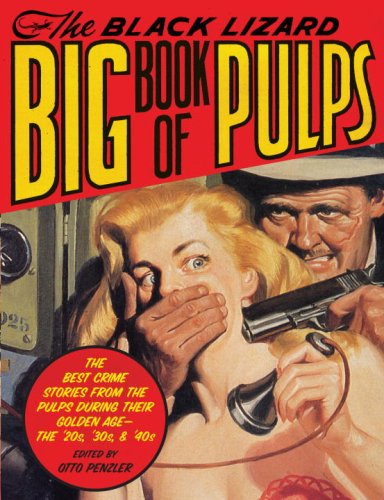

On my side of the Atlantic, crime fiction in the interwar years was as far from pulp as it is possible to get. For a start, pulp fiction was written by men—every one of the fifty-three authors featured in The Black Lizard Big Book of Pulps is male—while almost all the classic English crime writers were women. Essentially, too, these women were middle-class and wrote for middle-class readers; the lower orders got their fictional entertainment from the newspapers. The first crime novels that I read—or, better say, detective novels, since the crime was always of far less importance than its solving—had been written in the ’30s by Agatha Christie. I was reading them in the middle years of the bleak ’50s, when even ten-year-old boys were in need of diversion from the frightening realities of a world locked in a cold war that was steadily getting hotter. Good old Agatha. In her jacket photo—those steely curls, that set of perfect dentures—she was a dead ringer for everybody’s rich aunt. What could be cozier than to curl up on a wet Sunday afternoon with one of her magically unmenacing brainteasers?

From Aunt Agatha I moved on to more sophisticated members of the sorority, such as Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh—whose very name was a conundrum—Josephine Tey, Gladys Mitchell, Dorothy L. Sayers. What was it with these nice, politely brought-up women, what fantasies of violence and revenge did they harbor in their hearts, that so many of them turned to murder, if only fictionally? From the ’30s through to the ’60s, their brand of crime writing held sway in Britain and Irelandor These Islands, as our contentious archipelago used to be called. Certainly, in that period there were some notable male detective writers—the fiendishly clever Edmund Crispin, for instance, who in real life was Philip Larkin’s pal Bruce Montgomery, and Nicholas Blake, the poet Cecil Day-Lewis’s alter ego and boiler of pots—but they seemed on the whole an effete lot and could not hold a smoking revolver to the ladies.

In fact, the male crime writer who was most indebted to his female contemporaries, carrying the lessons they taught him halfway round the world to California, was Raymond Chandler, Chicago born but brought up in England from the age of seven. Sayers and Tey would, and probably did, recognize Chandler’s Philip Marlowe as a confrere of their suave sleuths, for Marlowe, like Tey’s Inspector Alan Grant and Sayers’s Lord Peter Wimsey, is nothing if not a gentleman, indeed, a parfit gentil knight, whose suit of shining armor illuminates the meanest of those mean streets down which he resolutely ventures.

On mature reflection, I consider the Marlowe books forced and even a touch sentimental, for all their elegance and wit and wonderful sheen—two of his stories, “Killer in the Rain” and “Finger Man,” sit uneasily in the Big Book of Pulps, like, to quote The Waste Land, a silk hat on a Bradford millionaire. Chandler perhaps labored too long and too hard at effecting the transmutation of life’s raw material into deathless prose. A far greater writer, James M. Cain, who was happy to keep it raw, who gloried, indeed, in the rebarbative, created a masterpiece, seemingly effortlessly, in The Postman Always Rings Twice. Although Cain was the most hard-boiled of them all, his original ambition had been to follow his mother’s example and become a classical singer, and music features frequently in his work—in the extraordinary novel Serenade, the protagonist, if that is the word, is an out-of-work opera singer on the lam in Mexico. Such are the odd conjunctions of the crime-writing milieu.

Cain contributes the finest story to the Big Book of Pulps. Titled, with bitter sarcasm, “Pastorale,” it is a first-person narrative by a nameless southerner, who might well be a native of Yoknapatawpha County, and tells of the fate of poor Burbie—“Well, it looks like Burbie is going to get hung”—who persuades his friend Hutch to join him in the robbing and murdering of an old man who they think is rich but who turns out to have “no more’n $23 in the pot.” After the deed is done, Hutch forces Burbie to decapitate the corpse and throw the head into the creek—or, rather, onto the creek, since to their chagrin it has frozen over; in attempting to retrieve the telltale evidence, Hutch falls through the ice and is drowned. Now Burbie seems in the clear, since Hutch is assumed to have been working alone, but Burbie is a talker and ends up confessing to the town constable, for no better reason than that it is too good a story not to tell. As the narrator says, “I reckon he done been holding it all so long he just had to spill it.” This is classic Cain—bloody, sardonic, and horribly funny—and “Pastorale” alone makes the Big Book of Pulps worth the purchase price.

I confess I came late to Cain—if he had chosen it, could he have hit on a more suitable name for himself?—as I did to the work of Richard Stark, real name Donald Westlake, whose Parker novels, a cluster of which were written in an extraordinary burst of creativity in the early ’60s, are among the most poised and polished fictions of their time and, in fact, of any time. Parker, whose first name we never learn, is the ultimate professional. He is a ruthless, calm, and efficient crook who kills only when he judges it necessary. We understand that he is a highly successful felon, yet almost all the books in which he features—there are some thirty by now, including Ask the Parrot, published recently and as good as the best of them—begin with something going disastrously wrong. And Parker is at his most inventive when at his most desperate.

One of the remarkable aspects of the Parker books is that, unlike pulp fiction, they are utterly without any notion of morality. In the fantasyland of the pulps, good must, and does, triumph. However, Parker’s world is the real world, and Parker’s disenchantment is total. Did Westlake read Georges Simenon? Did Simenon read Westlake? It would be good to know. Their visions of how things are in this bitch of a world, as Beckett has it, are very similar. For Simenon, like his American counterpart, life is a difficult, violent, and perilous business, the essential nastiness of which no extreme of wishful thinking will wish away. Simenon began his career as a reporter for the Belgian Gazette de Liége, then when still a young man he moved to Paris and began to churn out popular fiction under a plethora of pseudonyms. His most famous invention is, of course, Inspector Maigret, yet the very many books in which this laconic, pipe-smoking detective features are formulaic and even at times slapdash, betraying the haste in which they were written. But what he called his romans durs, or hard novels, such as Dirty Snow, Monsieur Monde Vanishes, Tropic Moon, and the masterly Strangers in the House, are among the finest existential fictions of the twentieth century, as good as anything by Camus or Sartre and far less precious and self-conscious. Perhaps Simenon’s only equal among French writers of his time is the great Louis-Ferdinand Céline.

Had he chosen to settle early in America, which he later did for some years, Simenon would certainly have written for the pulp magazines that flourished in the ’20s and ’30s, when, as Otto Penzler informs us in his foreword to his Big Book of Pulps, “more than 500 titles a month hit the newsstands. With their reasonable prices (mostly a dime or fifteen cents a copy), brilliantly colored covers depicting lurid and thrilling scenes, and a writing style that emphasized action and adventure above philosophizing and introspection, millions of copies of this new, uniquely American literature were sold every week.”

Penzler, proprietor of the indispensable Mysterious Bookshop in New York City, has collected his stories from magazines such as Dime Detective, Detective Fiction Weekly, and, of course, the greatest and most influential of them all, Black Mask, which published, among others, Chandler, Erle Stanley Gardner, George Harmon Coxe, Paul Cain, and Dashiell Hammett, who wrote his first Continental Op story for the magazine. As Penzler writes, “Had it done no more than publish Carroll John Daly’s first story (‘Three Gun Terry’), Black Mask would have achieved immortality.” The story appeared in the issue of May 15, 1923, and its hero, Terry Mack, “served as the prototype for all the tough, wise-cracking private dicks who followed.” Daly (1889–1958) also invented the first “series” hard-boiled investigator and righter of wrongs, Race Williams. “Three Gun Terry” is not included, wisely, we must assume, in the Big Book of Pulps, but we are treated to a novella-length yarn by Daly, “The Third Murderer.” It is a pretty awful piece of work, yet from the opening lines we can see clearly why the genre caught on:

I didn’t like his face and I told him so.

He was handsome enough in a conceited, sinister sort of way. And the curve to the corner of his mouth was natural too—but more pronounced now by the involuntary twitching of his upper lip; a warning that a lad is carrying too much liquor and is getting to the stage where he’ll slop over. Which is his own business, of course, and not mine—except when that lad decides to slop over on me.

Penzler sensibly makes no claims for the quality of most of the stories gathered here. What he says briskly of Daly, that he was “a hack writer devoid of literary pretension, aspiration, and ability,” could as well be said of the majority of the writers whom he has included. The stories published in the pulps, he observes, were “written at breakneck speed and designed to be read the same way.” (By the way, the term pulp was not a pejorative judgment, but simply a denotation of the material, wood pulp, from which the coarse gray paper used in the magazines was made.)

The deepest satisfaction we derive from crime fiction, whether we know it or not, is the sense of completion it affords us. Life is a mess—we do not remember being born, and death, as Ludwig Wittgenstein wisely observed, is not an experience in life, so all we have is this chaotic middle bit, bristling with loose ends, in which nothing is ever properly over and done with. It could be said, of course, that all fiction of whatever genre offers a beginning, middle, and endeven Finnegans Wake has a shape. But crime stories do it better. No matter how unlikely the cast of suspects or how baffling the strew of clues, we know with rare certainty that when the murderer is unmasked, as he or, more rarely, she inevitably is, everything will click into place, like a jigsaw puzzle assembling itself before our eyes. The stories in the pulp magazines were less deterministic than their classier English equivalents, but they, too, specialized in imposing order on a disorderly world.

Crime fiction flourishes in hard times. The fiction reflects the times, and the times color the fiction. There is a rawness in the pulp stories, even those by “literary” writers such as Chandler and Hammett, that is not due entirely to the exigencies of the marketplace. At their best, and even, perhaps, at their worst, these yarns express something of the unforgiving harshness and dauntless optimism of life in America in the decades between the wars. Of course, the plots are almost uniformly absurd. As Penzler writes:

It was a black-and-white world in the pulps, a simple conflict between the forces of goodness and virtue and those who sought to plunder, harm, and kill the innocent. In the pages of the pulps, and between the covers of this book, Good is triumphant over Evil. Perhaps that is the key to the enormous popularity they enjoyed for so many years.

Who can wonder at such popularity, given the low, dishonest decades in which the pulps sold by the millions? The world had come out of one calamitous world war and was heading in a handcart for another, and in between there was the Great Depression to be survived. To defeat the villains ravening the real world required a collective and well-nigh superhuman effort, with the expense of countless innocent and mostly working-class lives, but in the pages of the pulps one good man could triumph over all adversity. Even the dimmest readers knew it was a hopeless fantasy, but so what? Dreams were cheap, at a dime a dozen.

The Big Book of Pulps is divided into three sections, “The Crimefighters,” “The Villains,” and, of course, “The Dames.” Penzler, the overall editor, contributes an introduction to the first that opens with a telling comparison between pulp fiction and jazz, another “entirely . . . American invention.” A jaunty Harlan Ellison, best known as a science-fiction writer, introduces “The Villains” with the boast that “mine is exactly the proper vita for a book’a’crooks,” since in his early days he wrote for “Manhunt, Mantrap, Mayhem, Guilty, Sure-Fire Detective, Trapped, The Saint Mystery Magazine (both U.S. and U.K. edition), Mike Shayne’s, Tightrope, Crime and Justice Detective Story and Terror Detective Story Magazine, just to glaze your eyes and bore yo ass with a select few of the rags for which I toiled.”

“The Dames” is introduced by the best-selling crime writer Laura Lippman, who observes mildly that “the pulps of the early 20th century will never be mistaken for proto-feminist documents.” This is true. As Penzler remarks, what pulp fiction mostly did was provide “opportunities for placing luscious young beauties in grave peril of violation.” One of the merrier inclusions in this section is a ’30s comic stripapt descriptiondevoted to the adventures of Sally the Sleuth, by one Adolphe Barreaux (1899–1985). Though you might not guess it, this artist “studied at the Yale School of Fine Arts and the Grand Central Art School.” The redoubtable Sally always gets her man, and in the process, every time, loses most of her clothes.

The women are perhaps the most interesting characters in the pulps. “They are,” Penzler notes, “young and old, good looking and not, funny and dour, brave and timid, violent and gentle, honest and crooked.” However, Lippman remarks, “even if women seldom take the lead in these stories, there is just enough kink in these archetypes of girlfriend/hussy/sociopath to hint at broader possibilities for the female of the species.” In this context, I was greatly taken with Jeanne Delano, in Hammett’s story “The Girl with the Silver Eyes,” who ends up in the delicate position of having to refuse to make a statement until she has seen her attorney.

As she was being led away, she stopped and asked if she might speak privately with me.

We went together to a far corner of the room.

She put her mouth close to my ear so that her breath was warm again on my cheek, as it had been in the car, and whispered the vilest epithet of which the English language is capable.

Then she walked out to her cell.

Oh dear, what would Aunt Agatha have said?

The Big Book of Pulps is a Herculean, or it might be better to say Sisyphean, effort at an overview of one of the more fascinating genres of popular fiction. Browsing through these tales of murder, mayhem, and the fight for right, one keeps seeing through the page to the image again of those original readers, mired in hard times and looking for escape, if only into the dream of a world where men were men and women loved them for it, where crooks were crooks and easily identified by the scars on their faces and the gats in their mitts, where policemen were dull but honest and never used four-letter words, where a good man was feared by the lawless and respected by the law-abiding: In short, where life was otherwise, and better.

John Banville’s crime novel Christine Falls was published in 2006 by Henry Holt under the pseudonym Benjamin Black.