Donald Barthelme was the Stephen Sondheim of haute fiction—a dexterous assembler of witty, mordant, intricate devices that, once exploded, exposed the sawdust and stuffing of traditional forms. His stories weren’t finely rendered portrait studies in human behavior or autobiographical reveries à la Johns Updike and Cheever, but a row of boutiques showcasing his latest pranks, confections, gadgets, and Max Ernst/Monty Python–ish collages. Like Sondheim’s biting rhymes and contrapuntal duets, Barthelme’s parlor tricks and satiric ploys were accused early on of being cerebral, preeningly clever, hermetically sealed, and lacking in “heart”of supplying the clattering sound track to the cocktail party of the damned. Yet, like Sondheim, Barthelme was no simple Dr. Sardonicus, licensed cynic. His radiograms from the observation deck of his bemused detachment evidently touched depths and won converts, otherwise his work wouldn’t have inspired so many salvage operations intended to keep his name alive and his enterprise afloat. Mere smarty show-offs don’t garner this kind of affection from a younger breed of astronauts. Just as there always seems to be a Sondheim musical poised for Broadway revival (Company in 2006, Sunday in the Park with George right now), Barthelme’s bundle of greatest hits and obscure outtakes has been parceled out in a series of reprintings and repackagings since his death in 1989. He’s always poised on the verge of being majorly rediscovered without ever quite making it over the crest, despite the valiant huffing done on his behalf.

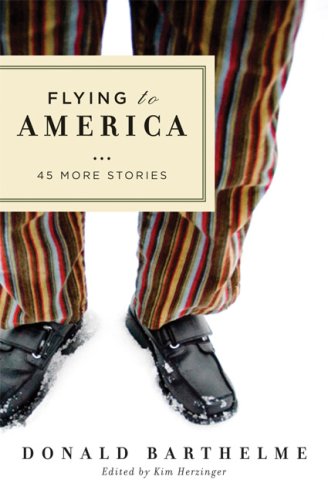

With the publication of Flying to America: 45 More Stories, edited by Kim Herzinger (a teacher at the University of Southern Mississippi and Barthelme’s chief curator and evangelist), the long, exhaustive reclamation project is complete. Unless a few unpaid parking tickets or napkin doodles turn up somewhere, the final load of Barthelme’s literary catalogue has been carved free from the catacomb, the final tally entered on the tote board. “Sixty Stories, it was once said, was Barthelme’s attempt to establish his canon,” Herzinger writes in the preface. “Forty Stories, then, might be seen as his attempt to enlarge it. Flying to America: 45 More Stories, which contains every story not collected in any of the individual published volumes, and three previously unpublished stories, is a crucial addition—perhaps the crucial addition—to his existing canon.” Yet how crucial is “crucial”? If Sixty Stories (1981) represents Barthelme’s core strengths as an alchemist of the banal baroque, his primary bid for literary immortality, and Forty Stories (1987) expands on the claim, does serving up a batch of leftovers truly address a crying need? Isn’t there a danger that by catering to the junkies and the completists, you end up burying the brand under excess inventory? Along with indisputable classics (“The Balloon,” “Robert Kennedy Saved from Drowning,” the story “The Dead Father,” and others to be mentioned), Barthelme left behind a fair amount of clutter, trinkets, and ephemera. Their bio-historical interest lends little to his legacy. I’m reminded of those CD boxed sets that feature two or three outtakes of the same song—much as I love the Velvet Underground’s “Sister Ray,” three versions of it creates a tunnel effect, complete with echo chamber.

So, too, here. Flying to America’s title story—a deadpan account of a visionary filmmaker’s travails (“An old woman was bent over my garbage can, borrowing some of my garbage. They do that all over the city, old men and old women. They borrow your garbage and they never bring it back”) that presages director David Lynch’s quest to x-ray the dark psyche (“Today we photographed fear”)—is a scrap heap of reusable parts. According to Herzinger’s endnotes, the story draws on material first published in a New Yorker Notes and Comment in 1970. Other passages were later included in a story called “A Film” (reprinted in Sadness [1972] as “The Film”), and still other bits were “resurrected” (Herzinger’s word) in a story called “Two Hours to Curtain” and in the novella The Dead Father (1975). So we’re not talking about a mint find here, whatever its piquant attributes and Steven Wright–like koans (“My answering service refuses to speak to me”). Similarly, many if not most of the other stories in Flying to America have been retrieved from out-of-print collections such as Come Back, Dr. Caligari (1964), Amateurs (1976), and Unspeakable Practices, Unnatural Acts (1968). Seeing them again may quiver the fine hairs of those fiction fiends who grew up on Barthelme and who will savor once again the Borscht Belt shtick of “The Piano Player”—“‘You’re supposed to be curing a ham.’ ‘The ham died . . . I couldn’t cure it’” (note to future Barthelme scholars: His stories are rife with references to ham, pigs, and hogs just crying out for explication, so get cracking, kids!)—and enjoy becoming reacquainted with riffs that unfold like card tricks and once-trendy cultural references that summon the dashing heyday of metafiction (“She read R. D. Laing. Aloud, at dinner. Every night”). But what about virgin readers, Barthelme newbies, and other babes in the manger? Will these stories light up their button eyes like birthday treats? Or are they exquisite but arid, lifeless arrangements of painted dice, owl pellets, and bric-a-brac—Cornell boxes from which the mystery has flown?

Such questions arise because part of the original exploding-alarm-clock novelty of Barthelme’s Pop fiction was the pristine context in which it was first presented—the modest decor with which it clashed. Take, for instance, “The Indian Uprising,” accepted by fiction editor Roger Angell with a telegram to Barthelme that read INDIAN UPRISING UPROARIOUS. PALEFACES ROUTED, SHAWN SCALPED. IN SHORT, YES and published in the New Yorker of March 6, 1965. A Vietnam allegory whose incantatory ironies evoke the fine cuticles of T. S. Eliot, its energy and invention burst out of the gate from its famous opening paragraph of Comanche arrows descending in clouds on a tableau of bourgeois malaise—“‘Do you think this is a good life?’ The table held apples, books, long-playing records. She looked up. ‘No’”—to the swath of carnage that leaves children laid waste by helicopter fire. The anarchist force of “The Indian Uprising” would have stood out anywhere, but in the porcelain pages of the New Yorker, sharing space with luxury-carpet ads and chuckling nods of constipated whimsy from the Talk of the Town, it was like a reveille ripping through a conservatory. As Ben Yagoda wrote in About Town: The New Yorker and the World It Made, “The Indian Uprising” and a subsequent story, “A Picture History of the War,” messed with the reader’s mind: “With their imagery of war and torture and guerrilla forces on patrol, they also offered uncanny auguries of the street conflicts and jungle warfare that would soon insinuate themselves into the videotape loop running through the national consciousness.” Likewise, Barthelme’s rogue retelling of Snow White, which took up a huge chunk of real estate in the February 18, 1967, issue (nearly one hundred pages), looks almost insurrectionary in its impudence, brandishing boldfaced maxims and proclamations that anticipated Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer—“Anathematization of the World Is Not an Adequate Response to the World”—in the face of ads for Connie Francis and Pat Cooper at the Copacabana and Brendan Gill’s pithy review of Tobruk (“the Jewish commando is played by George Peppard”). Yagoda informs us that “Snow White” prompted an influx of mail that was unparalleled for a piece of fiction—nearly all of the letters either outright unfavorable or irritated-puzzled. But the New Yorker didn’t lose its nerve when its readers lost theirs, a rare, cherishable example of institutional composure and loyalty to talent.

Over the years, Barthelme’s antic break with the traditional tactful manner of the classic New Yorker story, where every stick of furniture and motivation was neatly, firmly in place, would expand into an entire wing of the magazine’s house style. His mastery of incongruity and curveball allusions helped liberate the whiz brains in the office and scramble the genetic code of the magazine’s humor and fiction irregulars: By the ’70s, the set-piece fictions and “casuals” of Ian Frazier, Veronica Geng, Mark Singer, Marshall Brickman, and George W. S. Trow abounded with absurdist dialogues, box scores, chess notations, chicken-scratch scribblings, send-ups of familiar minigenres (liner notes, movie blurbs, capsule reviews, wedding notices), multiple-choice quizzes, and mash-up satires (Geng’s specialty—assigned to write a new intro to Dwight Macdonald’s anthology Parodies: An Anthology from Chaucer to Beerbohm—and After, she pretended to have him confused with the mystery novelist John D. MacDonald, the creator of Travis McGee, and cast Robert Benchley in the part of “the Vietnam vet who drifted freely between the glittering cabanas of the Fun Coast and the oil-stained walkways of a derelict marina”). They ran riot while Ann Beattie stood slightly off to the side, strumming her hair.

Today, I would hazard (I’ve always wanted to hazard), the track marks of Barthelme’s suave, subversive cunning are to be found less in postmod fiction—although David Foster Wallace’s dense foliage of footnotes suggests a Barthelmean undergrowth and George Saunders’s arcade surrealism has a runaway-nephew quality—than in the conscientiously oddball, studiedly offhand, hiply recherché, mock-anachronistic formalism of McSweeney’s, The Believer, The Crier, and related organs of articulate mumblecore. In issue 24 of McSweeney’s, Barthelme is feted with a handsomely produced tribute package, whose introduction by Justin Taylor calls for “the belated and immediate beatification of Donald Barthelme” and deplores the diaspora of his oeuvre (“There is no wide-spine, low-price Donald Barthelme Reader that you can pick up on a whim and wave around like a jacked-up Mormon”). The McSweeniad includes two uncollected early stories and reminiscences from friends, colleagues, and admirers such as Beattie, Lawrence Weschler, Grace Paley, Padgett Powell, and Robert Coover (whose contribution, in its entirety, is “Donald was laconic”—yup). Most of the entries are literary-panel-discussion platitudes and anecdotes spruced up with a finer brushstroke and a warmer tone to produce a generously balanced group portrait that’s slightly on the boring side. Certainly, for me, biographical interest tapers off once Barthelme trades the folkie-jazzy confines of Greenwich Village (the one time I met B. was when I was manning the reception desk at the Village Voice, then on the same street as his apartment) for the campus of his alma mater, the University of Houston, where he taught literature and, according to one testimony, “his one-liners took on a life of their own, circulating in committee rooms and hallways and Board of Regents meetings.” Faculty humor, such a fleeting bird, and one’s heart sinks a little at the disclosure that his students bestowed on him the endearing nickname Uncle Don. It’s so domesticating. The most instructive and valuable entry in the McSweeney’s comes from, yes, George Saunders, the outlaw nephew, who suspensefully analyzes the story “The School”—“How’s he going to take this Marx Brothers–quality romp and convert it at the last minute into a Postmodernist Masterpiece?”—and hits on Barthelme’s key stratagem: “Mr. Lesser Writer, in other words, realizing with joy that he has a pattern to work with, sits down to do some Thinking. Barthelme proceeds in a more spontaneous, vaudevillian manner. He knows that the pattern is just an excuse for the real work of the story, which is to give the reader a series of pleasure-bursts.”

Bang! Exactly! Spastic rhapsodies of silver staccato! Pleasure bursts are what it’s about in Barthelme, cherry bombs flung into a crowd of elegant pretenses to fend off unconditional surrender to the fetal curl of melancholy. “Melancholy,” muses Thomas Pynchon in the introduction to The Teachings of Don B. (1992), a collection of satires, fables, illustrated tales, and whatnot edited by Herzinger. “Barthelme’s was a specifically urban melancholy, related to that look of immunity to joy or even surprise seen in the faces of cab drivers, bartenders, street dealers, city editors, a wearily taken vow to persist beneath the burdens of the day and the terrors of the night. Humor in these conditions leans toward the anti-transcendent—like jail humor and military and rodeo humor [rodeo humor?], it finds high amusement in failure and loss, and it celebrates survival one day, one disaster, to the next.” Never a slave to linearity or other tightly laced narrative conventions, Barthelme converted the short-story format into a highbrow variety revue. Framing a number of his stories as little theatricals (some are written as play scripts or as updated Mike Nichols–Elaine May routines), Barthelme had the pinpoint timing of a John Osborne or a Harold Pinter springing a booby trap, knowing just when to insert a barbed putdown or macabre joke to get a gargoyle grin going. He was a highly acute technician of tension creation and release. But as Barthelme became a known quantity, it became harder for him to smuggle a joy buzzer into his latest masquerade, and the mélange of high-low juxtapositions (“ragout of Spinoza and Cyndi Lauper with a William Buckley sherbert floating in the middle of it”—“Paradise Before the Egg,” originally published in Esquire, 1986) lost its novelty. A number of the stories in Flying to America have the nimble finger work of formal exercises and changes being rung, such as “The Agreement,” which consists almost entirely of self-plaguing questions (“Having assigned myself a task that is beyond my abilities, why do I then do that which is most certain to preclude my completing the task? To ensure failure? To excuse failure?”), or the even more Kafkaesque “A Man,” a brief fable about a fireman who wakes up one day with his left hand mysteriously gone—poof, like that. Excused from his duties, he tries to make the best of it, telling himself: “I am a finished fireman. . . . But yet, a human being, I have courage, resiliency—even hope. I will remold myself into something new, by reading a lot of books. I will miss firehouse life, but I know that other lives are possible—useful work in a number of lines, socially desirable activities contributing to the health of the society,” only to have his wishful thinking dismissed with the sneering comment “The fireman told himself a lot more garbage of this nature.” It’s an oddly direct jab by an author who usually played it so elliptical, or, as Elvis Presley would say, “ob-leek.” Perhaps Barthelme got tired of peeling off wacky non sequiturs to divert his fans—such as “Dancing on my parquet floor in my parquet shorts. To Mahler” (from “Can We Talk”)—and decided to strip away a few illusions instead. (Reading the fireman’s list of miserable lessons he has learned from his loss, his acknowledgment of his newfound sense of loserdom, I couldn’t help but think of Sondheim’s acid-drop mortality ode in A Little Night Music—“Every Day a Little Death.”) When Barthelme’s harlequinade faltered and his contoured mask slipped, you could hear the alcohol talking in his spite and sunken morale. “From Barthelme to Pynchon there is a sense of booziness, nausea, hangover,” observed Gore Vidal in his famous aerial bombardment of New Fiction experimentalists, the papal edict “American Plastic: The Matter of Fiction” (1976). I’m not sure Barthelme’s reputation ever quite recovered from the cuffing it took from Vidal’s velvet paws. It certainly lost its gloss. His avant-gardism was made to look derivative of that of Alain Robbe-Grillet, Nathalie Sarraute, and other French New Novelists, a contrived pose. Critical esteem was vital to Barthelme’s well-being as an author, because popular support never materialized. Mark Jay Mirsky, who founded Fiction magazine in 1972 with Barthelme and a few others, writes in the McSweeney’s symposium that Barthelme felt the sore throb of being underappreciated: “Donald’s collections of short stories, I believe, never exceeded nine thousand copies in hardback, despite the enthusiastic reviews and his regular appearance in the New Yorker.”

But it’s a newish century, and look where we are. The exactitude and hospital gleam of the Nouveau Roman is a forgotten fashion while Barthelme’s musical carousel still beckons, raising its painted hooves. Chalk one up for the home team. Either from a concerted campaign or a fluky convergence, or some combination, there’s clearly an upward draft in the zeitgeist to loft Barthelme’s status from cult figure to godfather guru. In The Dead Father, perhaps his flagship work, a battalion of children tote their dead father’s Gulliver-size body for burial; what we have here is the resurrection of the dead father by his literary offspring, his restoration to the throne. If the anguished ghost of Leonard Michaels can get a second chance and a more favorable ruling from the critical judiciary with the republication of Sylvia and The Collected Stories, Barthelme would seem equally deserving and due for revival (with John Hawkes waiting on deck). Along with the publication of Flying to America and the McSweeney’s portfolio, Counterpoint is reprinting The Teachings of Don B., which includes his classic account of The Ed Sullivan Show, his hilariously lackadaisical Batman romp “The Joker’s Greatest Triumph” (which mysteriously incorporates biographer Mark Schorer’s character analysis of Sinclair Lewis), and perhaps my all-time favorite Barthelme opening sentence (“My deranged mother has written another book”), along with the miscellaneous Not-Knowing: The Essays and Interviews (1997). Novelist Richard Ford included Barthelme’s story “Me and Miss Mandible” in The New Granta Book of the American Short Story, which he edited last year, and the October 2007 issue of the Yale Review contains an essay by Richard Locke that places Don B. in pantheonic company: “Details in Nabokov, Barthelme, and Proust.” Despite this on-swell, I suspect that there’s a natural ceiling to Barthelme’s devotional following that no amount of critical hoopla or hero worship will crack. Barthelme will never be a popular icon because his iconography is all in his work and leaves nothing for the average hero worshiper to emulate. He isn’t angsty, like Michaels, a mysterioso phantom, like Pynchon, or a rumpled oracle, like Vonnegut. His fan base probably will always be a select band of aspiring wizards, and why should that be a cause for lament? Enshrinement as a writer’s writer—a James Salter, a Gilbert Sorrentino; his friend Grace Paley—is surely a kinder fate than the desuetude that has befallen so many of Barthelme’s New Fiction contemporaries. In “The Sea of Hesitation,” reprinted in Flying to America, the narrator reflects, “I pursue Possibility. That’s something.” Barthelme did more than pursue Possibility—he enriched it, leaving the playground bigger and brighter than he found it. He is in no further need of special pleading.

The recipient of the National Magazine Award for Reviews and Criticism in 2003, James Wolcott is a columnist and contributing writer at Vanity Fair and a blogger on the magazine's website.