In the summer of 1965, the poet Robin Blaser discovered his friend Jack Spicer lying comatose in the poverty ward at San Francisco General. The forty-year-old Spicer had passed out drunk in the elevator of his North Beach flat a few days before and was wheeled in, without ID, in a torn and befouled suit. When an attending doctor suggested to Blaser that Spicer was just your typical middle-aged alcoholic, Blaser grabbed the fellow’s shirt: “You’re talking about a major poet.” This was certainly true at the time, and it is now. But then, Spicer was a dying poet. After days of fever and mumbling, he managed to shape what would be, more or less, his last coherent sentence. “My vocabulary did this to me,” he said.

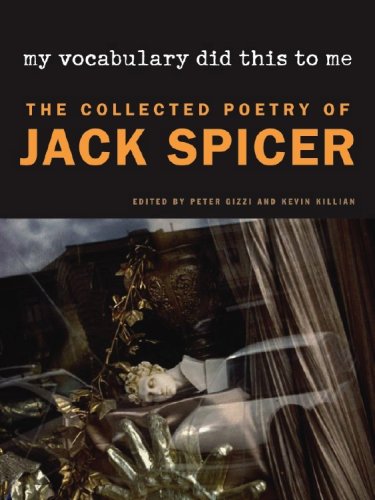

These final words serve as an apt title for Peter Gizzi and Kevin Killian’s wonderfully edited Spicer collection, the first thorough gathering of the poet’s extraordinary and challenging writing to appear since the ’70s. The phrase itself could be a line from one of his mature poems: matter-of-fact and bleakly funny, like the recoil from some inconclusive blow in a verbal joust. A similar voice closes one of Spicer’s best-known poems, an invocation of the ocean that crowns the late sequence “Thing Language”:

Aimlessly

It pounds the shore. White and aimless

signals. No

One listens to poetry.

Spicer wrote from that pounded shore, a site as geographic as it was Orphic. Born in Los Angeles to midwestern stock, Spicer was a fiercely regional writer, a proud habitué of Berkeley and North Beach who hated New York and loved loved loved the Giants. With Blaser and Robert Duncan, two other homosexual poets he met at UC Berkeley in the late ’40s, Spicer helped establish one of the most thriving communities within the motley fabric of the San Francisco Renaissance. In bars and in his beloved Aquatic Park, Spicer actively (and fractiously) cultivated a highly social circle of poets and artists and influenced writers like Jack Gilbert and Richard Brautigan, who dedicated Trout Fishing in America to the poet. Spicer was so committed to the local that he insisted on limiting the distribution of his publications to the Bay Area, as if poetry were a kind of community-supported agriculture. (He also, presciently, refused copyright.) But though he cofounded the “6” Gallery, the site of Ginsberg’s legendary howl, Spicer was no Beat—he disliked pot, thought Zen was stupid, and made fun of Ferlinghetti. “Be bop de beep / They are asleep,” he wrote in 1960.

The young Spicer proclaimed that he wanted to write a poem “as long as California,” but the state he rendered into verse was more than a place of fogs and cliffs or even “The sea- / Coast of Bohemia.” California’s geography also staged a liminal poetics, what Robinson Jeffers—the brooding and misanthropic poet of isolated Carmel, whom Spicer very much admired—called “the verge extreme.” Spicer stalked that verge, loosing the discourses that bind the self. Though his early lyrics are well wrought and often disarmingly beautiful, his mature writing is a vexed threshold of sense and nonsense, a jagged, pun-strewn, and sometimes harrowing crossroads of romance and straight talk, machines and the voices of the dead. “Fifteen False Propositions Against God,” written in 1958, contains a striking example of Spicer’s skittering play of interruptions and arresting images:

Beauty is so rare a th—

Sing a new song

Real

Music

A busted flush. A pain in the eyebrows. A

Visiting card.

Poetry with such cross talk asks a lot of the reader, of course, and Spicer—who dismissed poems that easily please their audience as “whorish”—is a notoriously tough nut to crack. Much of this difficulty is both explained and illuminated by his peculiar poetics. Unlike his Beat peers, Spicer did not believe that poetry should be the expression of an inspired and uncorked self. Instead, the poet’s work is reduced to an almost mechanical act of listening to and receiving what Spicer called the Outside—a field of forces that invade rather than inspire, and before which the poet is little more than a secretary taking dictation. In a fascinating series of lectures that he gave in Vancouver shortly before his death (and that can be heard, slurs and all, at PennSound, the University of Pennsylvania’s online-audio project), Spicer explains that the poet’s task is to get himself—his loves, his plots, his beloved meanings—out of the picture, so that what he only half-humorously calls “spooks” or “Martians” can enter. The content of the poet’s mind, his memories, lore, and language, is just “furniture” that the Outside arranges into a poem, a process that Spicer compares to a Martian arranging a kid’s alphabetic blocks to form a message.

Spicer’s concept of poetic dictation, not to mention the word puzzles it catalyzed, owes a great deal to the poet’s formal training and occasional research in pre-Chomskyan linguistics. At the same time, the Vancouver lectures make clear that Spicer approached poetry as an effectively spiritual practice, one that demanded both an ascetic erasure of the personal and a practical engagement with the tradition of spiritualist poetics. Spicer begins his first lecture with a description of the spirits that, in addition to inspiring W. B. Yeats’s A Vision, brought the aging Yeats “metaphors for [his] poetry.” Tellingly, Spicer places Yeats and his wife, George Hyde-Lees, on a train from San Bernardino to Los Angeles when she first establishes contact through automatic writing. Spicer is probably bullshitting here—there is no evidence for the claim—but his desire to establish a West Coast tradition of oracular aesthetics is palpable.

Spicer’s own initiation into occult poetics occurred when he met Duncan at Berkeley in 1946, a year Spicer once proclaimed as that of his real birth. A native Californian whose adoptive parents belonged to a theosophical order, the older Duncan introduced Spicer to a nuanced but overtly magic approach to poetry—a literate and deeply aesthetic hermeticism that also cast a glamorous light on the gay demimonde that surrounded Duncan and drew the awkward Spicer out of his shell. Along with Blaser and others, the young men experimented with parlor games, spiritual dictation, and bibliomancy and began developing an esoteric bravado that Charles Olson later attacked, in his essay “Against Wisdom as Such,” as an “école des Sages ou Mages as ominous as Ojai.” But though Spicer later taught a workshop at San Francisco State called “Poetry as Magic,” he never confidently embodied the magus the way Duncan did. Linguistically sophisticated, a lover of puzzles, Spicer was content to treat the occult as another game, a contest of signs playing hide-and-seek with meaning. What seemed most important for Spicer was the practice of dictation itself, a practice that demanded a dismantling of what he called “the big lie of the personal.” In his Vancouver lectures, Spicer describes taking hour after agonizing hour to clear out his mind enough for a handful of truly dictated lines to appear.

Does Spicer’s spectral poetics represent a last-gasp Romanticism or a decisively postmodern turn toward the abject and the nonsubjective materiality of language? This fluctuation is fundamental to his poetry and accounts for much of its relevance and power. On the one hand, the muse of Tradition has been body-snatched by one of William Burroughs’s alien viruses, whose codes and messages, Spicer insists, are not necessarily right or wise or beautiful. But behind this science-fictional frame—rooted in part in Spicer’s love of Astounding Stories and pulp writers like Alfred Bester—is a more traditionally Orphic stance, which finds the poet cocking his ear to the ocean beyond and transmitting its white noise and ghostly signals into the tangles of our fixed tongue. One of Spicer’s favorite images for this process is, in fact, the car radio in Cocteau’s film Orpheus, which broadcasts verses from a deceased poet—verses that the handsome Orpheus transcribes obsessively.

This circuit of parasitic haunting also forms the framework for Spicer’s 1957 breakthrough, After Lorca, a collection of purported translations of the Spanish poet. The book opens with an introduction from the dead Lorca, who complains, justifiably, that Spicer has taken undue liberties with the translations that follow, and that some poems are not his—Lorca’s—at all. Not only do Spicer’s translations interrogate originality, they recast the poem as a kind of time machine, or what he elsewhere calls a “machine to catch ghosts.” Most of these ghosts are other poets throughout time, “patiently telling the same story, writing the same poem.” But one of these captured specters, it begins to dawn on the reader, is none other than you—you and the voice now in your head, dictating a poem like “Alba”:

If your hand had been meaningless

Not a single blade of grass

Would spring from the earth’s surface.

Easy to write, to kiss—

No, I said, read your paper.

Be there

Like the earth

When shadow covers the wet grass.

After Lorca was Spicer’s first realization of the serial poem, a form he shared with Duncan. Dismissing his earlier, stand-alone writings as “one night stands,” Spicer wrote nearly all his mature poems in series. Though he did continue to write and submit single poems for publication until his death, his serial poems were often published, independently, as small books. The Holy Grail (1962), which includes seven “books” with seven untitled poems each, is the most balanced and structurally harmonious of these works, even as the clash of its voices, images, and beats creates, as Spicer himself acknowledged, an “uncomfortable music.” The sprawling lack of closure inspired by the serial poem also invites us to read my vocabulary itself as a serial “book of Jack.” For though it is too much to say that there is unity in its diversity, there is, beyond the repeated images and tropes (lemons, rope) that reward tracking throughout his career, an essential condition to this work, even if that condition is nothing more than “a simple hole running from one thing to another.”

Any attempt to read that hole holistically, however, runs against the heterogeneity of its materials—not just poems but prose fragments, commentaries, a “textbook,” and personal letters Spicer presented at readings, thereby blurring public and private. And the poems themselves are patched together from all manner of language: ordinary speech, myth, epistle, foreign language, folk song, list, in-joke, street sign, homily, personal address, journal. Spicer wanted to make poetry a “collage of the real,” an ambition that linked him to West Coast visual artists like Bruce Conner, Wallace Berman, and George Herms, bohemian bricoleurs who created their assemblages from junk, pop culture, and oracular fragments. Rather than practicing some version of the cut-up, Spicer achieves the visceral sense of poetic collage through the intense and sometimes claustrophobic materiality of his language. Blaser noted that while Duncan sits comfortably within an almost regal sense of language supporting him, Spicer’s language is fully in front of him, like a “cubist painting where you can’t get through the fucking frame.” Spicer’s copious use of puns and syntactic ambiguity returns us to this consternating surface, where slips of the tongue turn poems into Möbius strips of meaning, figure-ground fluctuations over an essential groundlessness. This self-deconstructing passage through sound and sign marks Spicer as a prophetic postmodern and a crucial influence on the Language poets.

At the same time, Spicer never abandoned himself to the linguistic turn. On this, the poet is unambiguous: The Outside uses language but is not identified with it. In his 1960 masterpiece, The Heads of the Town up to the Aether, Spicer proclaims, “From the top to bottom there is a universe. Extended past what the words mean and below, God damn it, what the words are.” Like Wallace Stevens, whose metaphysical telegrams he sometimes echoes, Spicer remains a poet of the real, or at least of the mantic, tricksy zone where poetry touches the real. By staying open to this zone in all its undecidability, Spicer subjected himself to the Outside—an almost penitent supplication that helps explains his sometimes startling “God language.” There is, in the poet, a Puritan or even Calvinist strain of deeply American dread:

Mechanicly we move

In God’s Universe, Unable to do

Without the grace or hatred of Him.

As the ambiguity of whether “of Him” is possessive shows, Spicer’s Christianity is no less riddled than his other language games; his Logos is always condensing into what he called the Lowghost. For all the problems with the term gnostic, Spicer’s spirituality is perhaps best characterized as such. He named The Heads of the Town after a lost Gnostic text, and the title perfectly suits this tripartite book’s etheric fluctuations, its battles between divine and human love and between the warring poetic agendas of personal gain and impersonal transmission—what Spicer elsewhere distinguished as the difference between “pawnshops and postoffices.” The book’s third section, “A Textbook of Poetry,” is a prose work of immense noetic power, an oblique catechism that bears uncanny fruit under sustained meditation. Spicer considered it one of his greatest feats of dictation.

That said, “No / Gnostrum will cure the ills that are on the face of it.” And Spicer saw a vast conspiracy of ills, within poetry and within the world. By 1962’s “Golem,” he was offering a harrowing view of the economic, political, and linguistic “fix” we’re in—a claustrophobic scam, not unlike Burroughs’s concept of Control, that insures that transcendence in Spicer is always wily and furtive. In a marvelous letter to James Alexander, a young Hoosier poet who became one of Spicer’s most powerful romantic muses, included in this volume, Spicer speaks of the “random places” where “they” will deliver their missives: “A box of shredded wheat, a drunken comment, a big piece of paper, a shadow meaningless except as a threat or a communication, a throat.” This is not Ginsberg spotting Whitman in a California supermarket. This is Oedipa Maas wandering San Francisco in The Crying of Lot 49, looking for muted post horns.

There is an even stranger synchronicity lurking in Spicer’s California mysterium. In 1948, back in Berkeley, he and Duncan roomed briefly with a peculiar young man named Philip K. Dick, who once supplied an LP-recording device for their parlor games of poetic performance. As Killian and Lewis Ellingham point out in their definitive Spicer biography, Poet Be Like God, the books of Dick and of Spicer later became mirror images of each other, in theme as well as in imagery—grasshoppers, Martians, radios, salesmen, cities. Like Dick, Spicer was an impoverished and alienated artist for whom writing was, as Darko Suvin famously described the genre of science fiction, a motor of “cognitive estrangement.” Both are cult artists who wrote, it can seem, as much for our time as for theirs. Spicer, who worked with computers in the course of his linguistics research, wrote about silicon and punched IBM cards; he cannily foresaw, in 1962, an America ruled by networked computers. This is the America that “drowns itself with machines and weeping,” where “Death is not final. Only parking lots.” We can hear Spicer through all his uncomfortable music because he channeled something of our condition: all those angry spirits, that aimless noise.

Erik Davis is the author, most recently, of The Visionary State: A Journey Through California’s Spiritual Landscape (Chronicle, 2006).