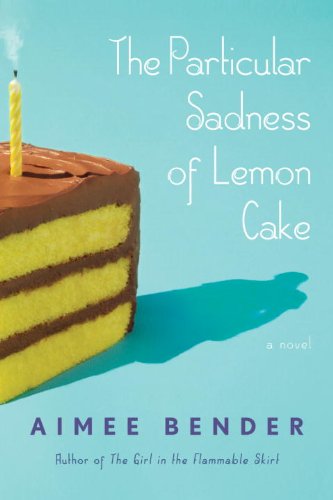

Like the mix of ingredients used to make the titular dessert in The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake, Aimee Bender’s novel is a blend of old-fashioned coming-of-age story and newfangled horror tale that becomes a less-than-satisfying confection about love, loss, and lunacy, and what they taste like in the preternaturally sensate mouth of one little girl. Bender, author of the story collections The Girl in the Flammable Skirt (1998) and Willful Creatures (2005) and the novel An Invisible Sign of My Own (2000), continues to explore a predilection for a kind of American-gothic postmodern realism with the story of Rose Edelstein, a California youngster blessed and burdened with the ability to taste human emotion in food and drink. Rose’s unusual gift, her burden, emerges during the “bright spring week” of her ninth birthday, almost a year after she developed a “strong love for sour” that was, perhaps, a precursor to the taste travails that follow. Arriving home from school one day, Rose finds her mother—who “enjoyed most . . . anything tactile”: tending flowers, stitching doilies, cabinetry work—baking her a lemon cake from scratch.

So far, so (sort of) normal. Yet when Rose breaks off a chunk of the still-cooling cake and ices it with chocolate frosting, something paranormal occurs. In the bite of birthday cake, Rose can detect her busy, sunny mother’s “smallness, the sensation of shrinking . . . a distance . . . a kind of lack of wholeness . . . that made it taste hollow. . . . She was not there, in it.”

Rose’s world is shaken and stirred, and for the remainder of this imaginative if vexatious book, Bender whips up episodic glimpses into the wacky behaviors of the child’s bizarre family. These include a father who is unable to drive by, let alone set foot inside, a hospital; a mother “raw with loneliness”; a brother “whose gaze was so unsettling people had to shove cereal boxes at him to get a break”; and Rose, “who couldn’t even eat a regular school lunch without having to take a fifteen-minute walk to recover.” Ever interrogative, Rose asks, “Who were these people?”

By way of an answer, Bender pushes her notion of a little girl who “can taste the feelings people don’t know they’re feeling” to at times unintentionally comic effect. There’s the scene where Rose eats a piece of pie baked by her mother and then slumps to the kitchen floor, tearing at her mouth and screaming, “Get it out!” Pages later, her uncomprehending mother is asking her daughter what is wrong, and Rose delivers a devastating coup de théâtre: “I TASTED YOU . . . GET OUT MY MOUTH!” What might have been a heart-wrenching moment devolves into melodrama.

When a fictional conceit outsmarts itself and strains belief, other aspects of the narrative must compensate. Happily, Bender is equal to the task. She vividly conjures Rose’s Los Angeles neighborhood, an area “in the flatlands near Hollywood” that is “bordered by Russian delis to the north and famous thrift shops to the south . . . combining families, Eastern European immigrants, and screenwriters who lived in big apartment complexes across the way . . . [who] stood out on balconies as I walked home from school smoking afternoon cigarettes.”

Bender is also adept at showcasing Rose in solitary, almost solipsistic moments, going about the business of being a child despite her intensifying affliction, which affects not only home-cooked food but everything she eats. With her parents frequently out of the house or otherwise distracted, and her reclusive teenage brother, Joseph, holed up in his bedroom, Rose makes do:

Sunday, I spent the afternoon watching TV. I rolled up my twenty-dollar bill and tucked it inside a jewelry-box drawer. I played twenty-five games of solitaire, and I lost twenty-four of the times, until I got so sick of the deck I took it outside and made the entire suit of diamonds into a streamlined fleet of mini paper-plastic airplanes. I put the final touches on my current-events modern world presentation, and then stared into space for a while, outside on the grass, surrounded by thirteen snub-nosed diamond-planes, crashed.

At the same time, Rose refers to “the acidic resentment” she can taste in grape jelly and to popcorn that registers on her tongue like “a puffy salty collapsing death.” These descriptions are hard to swallow because they seem purely poetic and not character-based, even when the character is a precocious nine-year-old. Another trouble spot comes in the appearance of George, Joseph’s only friend, a “half-white, half-black” physics geek with “galactic hair,” irresistible charisma, and a big heart. Rose’s crush on George, even as she grows older, keeps him returning to the story and stealing scene after scene. His steady rise into a successful grown-up life dovetails with Joseph’s brutal downward spiral, which provides the novel its ultracreepy-but-I’m-not-buying-it ending.

There is not enough expansive, sustained fancy here to lift the book into the realm of postmodern fairy tale. Instead, Bender’s gifts as a writer, displayed beautifully in the haunting stories of The Girl in the Flammable Skirt, feel stretched. With such powerful emotions ascribed to so many foods, the characters themselves become displaced from their feeling states, and their psychological reality gets diluted and dispersed—by everything from grated cheese to orange juice to oatmeal. While Bender deserves praise for her risk taking, what she’s concocted comes out of the vision oven a bit overcooked here, a little overdone there.

Lisa Shea is at work on a novel and is a contributing writer at Elle magazine.