AS AN INSTITUTION, the family is in the curious position of being regarded as both crucial to human survival and inimical to human freedom. It bears a note of bondage down to its root; family, that wonderfully warm, nourishing-sounding word (it’s the echo of mammal, mammary, mama, I suspect), derives from the Latin familia, a group of servants, the human property of a given household, from famulus, slave. Since its beginnings, family has carried this strain of being bonded—and not just in body but in imagination. “In landlessness alone resides the highest truth, shoreless, indefinite as God,” says Ishmael, setting sail in Moby-Dick. On shore, we are to understand, our minds remain manacled, too absorbed with the hearth to look up at the stars. The first thing the Buddha did in pursuit of enlightenment was to leave home (after naming his newborn son Rahula—“fetter”). For writers, the family has been posited as an especially hazardous pastime; as Cyril Connolly’s lugubrious forecast goes: “There is no more somber enemy of good art than the pram in the hall.”

But a swarm of recent books have been freshly interrogating the family as experience, institution, and site for intellectual inquiry: novels like Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill and 10:04 by Ben Lerner; memoirs like The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson, Ongoingness by Sarah Manguso, and Making Babies by Anne Enright; essay collections like 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write by Sarah Ruhl; and cultural studies like On Immunity by Eula Biss. In each, the arrival (or the imminent arrival) of a child prompts a constellation of questions about selfhood and artmaking and the ethics of care. Many of these books adopt a copious, fragmentary form and gesture, some a bit shyly, toward radical possibilities for the domestic. On canvases big and small, they test out new answers to ancient questions: How best can we live this life and how best can we write about it, to what ends and with what compromises?

We can detect familiar DNA throughout, echoes of defining memoirs like Adrienne Rich’s Of Woman Born (1976) and Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work (2001), both controversial in their time for addressing the tedium and isolation of caring for small children. And if there’s a presiding spirit, it’s gentle, generous D. W. Winnicott, the child psychotherapist who reified the power of “the ordinary mother in her ordinary loving care.” (Winnicott’s ghost also hovers over Alison Bechdel’s memoir Are You My Mother?) The books couldn’t be more diverse in tone, though: Ben Lerner’s metafiction is sweeping; Jenny Offill’s is stiletto-sharp. Sarah Manguso’s memoir is elliptical, and Sarah Ruhl’s and Anne Enright’s share the cozy chaos of Shirley Jackson’s recently reissued Life Among the Savages (1953). Eula Biss approaches the tinderbox of the anti-vaccination movement with every possible safety precaution in place—the carefully neutral tone, the extensive research. And Maggie Nelson’s book is a lava pool of shifting selves—she becomes pregnant while her fluidly gendered partner, the artist Harry Dodge, takes testosterone and has top surgery.

These books are committed to a kind of candor that surpasses confessionalism; there is an ethos of radical transparency at work, an interest in revealing just how the book we’re reading was produced, to out the kinds of labor that usually remain invisible. Rachel Cusk set the tone in A Life’s Work: “The issue of children and who looks after them has become, in my view, profoundly political, and so it would be a contradiction to write a book about motherhood without explaining to some degree how I found the time to write it.” She details the arrangements she made, how she cared for her daughter for the first six months while her husband worked, after which they moved from London to the country, him quitting his job, her writing full-time, a domestic experiment with very mixed results. Anne Enright follows suit in Making Babies: “I have flexible working hours, no commuting, I have a partner who took six weeks off for the birth of his first baby and three months for the second (unpaid, unpaid, unpaid). He also does the breakfasts. And the baths.” And Ben Lerner merrily shows his whole hand. His novel 10:04, which hews close to life, and also hinges on the birth of a child, contains descriptions of everything from how the book was conceived, pitched, and sold to how the author cannibalized his other writings to create it. There is no fantasy of a book’s immaculate conception here, just the good, grubby details.

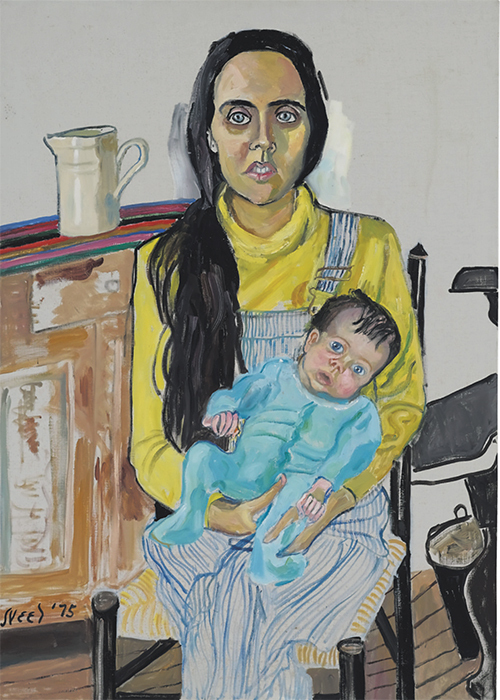

If child care is, as Cusk writes, “profoundly political,” so too is the labor of writing, so too are the questions of who writes and what about—and how can they afford to. In Dept. of Speculation, our narrator, a thwarted writer and new mother, recalls her early ambitions: “My plan was to never get married. I was going to be an art monster instead. Women almost never become art monsters because art monsters only concern themselves with art, never mundane things. Nabokov didn’t even fold his own umbrella. Vera licked his stamps for him.” These books reveal the rigging behind the art monster: Who licked the stamps on the applications for grants? Who minded the children? Who paid the bills, and how?

“The form our creativity takes is often a class issue,” wrote Audre Lorde. She was praising poetry, the most “economical” art form, the “most secret, which requires the least physical labor, the least material, and the one which can be done between shifts, in the hospital pantry, on the subway, and on scraps of surplus paper.” Toni Cade Bambara was fond of the short story for the same reason—its “portability”: “I could narrate the basic outline while driving to the farmer’s market, work out the dialogue while waiting for the airlines to answer the phone, draft a rough sketch of the central scene while overseeing my daughter’s carrot cake, write the first version in the middle of the night, edit while the laundry takes a spin, and make copies while running off some rally flyers.” (One can’t help but think of Karl Ove Knausgaard; would his avalanche of prose—those six volumes of minutely detailed domestic life—have been possible without Scandinavian social services, the day cares to which he and his poet wife were able to entrust their four children?)

Offill, Ruhl, Manguso, and Enright take to the fragment and to short bursts of prose for reasons aesthetic and epistemological, certainly, but also, one feels, out of some deeper exigencies—“I cannot hold my baby at the same time as I write,” Nelson writes. Enright says she wrote Making Babies in a frenzy while her babies slept and later assembled the book from her notes. The narrator of Offill’s Dept. of Speculation composes on grocery lists in the car, and scribbles on the backs of credit-card receipts. (Offill herself wrote her book on index cards.)

These aren’t the fragments—or the kinds of emotional fragmentation—made famous in the ’70s by Joan Didion, Elizabeth Hardwick, and Renata Adler, whose nervy, slender sentences evoked the chic ennui of women coming elegantly apart. This is a different kind of drift, a more painful unmooring. These shards are jagged—but they’re less a performance of alienation than a passionate effort at reconciliation. In interviews, Offill has said she wanted to capture how women, especially those passionate about their work, can feel estranged from themselves after having children. Dept. of Speculation is a self-portrait in shattered glass. In The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson’s fragments feel like units of resistance against the churn of conventional narratives about marriage, about the radical and normative, about narratives themselves. “When or how do new kinship systems mime older nuclear-family arrangements and when or how do they radically recontextualize them in a way that constitutes a rethinking of kinship?” she asks, borrowing language from the theorist Judith Butler. “How can you tell; or, rather, who’s to tell?”

And in 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write, Sarah Ruhl’s domestic dispatches careen from the theater to family life, creating a whiplash of competing loves and loyalties. She performs radical transparency by letting life come tumbling into the text, in the form of her three small children. They colonize her lap as she types; they slap at her keyboard, and she retains their “edits.” She can be wry about the interruptions—“I think of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own and how it needs a practical addendum about locks and bolts and soundproofing”—but generally embraces them. “There were times when it felt as though my children were annihilating me,” she writes. “Finally I came to the thought, All right, then, annihilate me; that other self was a fiction anyhow. And then I could breathe. I could investigate the pauses. I found that life intruding on writing was, in fact, life. And that, tempting as it may be for a writer who is also a parent, one must not think of life as an intrusion. At the end of the day, writing has very little to do with writing, and much to do with life. And life, by definition, is not an intrusion.”

We write as we live, with our particular privileges and constraints. (Offill quotes Wittgenstein: “What you say, you say in a body; you can say nothing outside of this body.”) In her recent essays for the New York Review of Books, Zadie Smith has made a point of delivering her disquisitions on joy, ambition, and gentrification as Ruhl does, while squeezing a small child into a snowsuit or rushing home to relieve a babysitter. Her children aren’t her subjects, but she keeps them in the frame, and they feel important. They’re part of how and where she does her work, her thinking. In her essay “Find Your Beach,” in which she marvels at how unencumbered one must be to survive in Manhattan, it’s 4 AM; she’s consoling a sleepless baby and she’s not speaking in abstractions.

Of course, invoking one’s children can be a tricky proposition for women writers, who run the risk of being labeled sentimental or unserious (fathers are inevitably immune). In The Argonauts, Nelson describes an ugly encounter involving the critic Rosalind E. Krauss, who—in a seminar, with the writer present—coolly condemned Jane Gallop’s work, in which she comments on photographs of her and her son. The charge, Nelson recalls, was that “Gallop’s maternity had rotted her mind—besotted it with the narcissism that makes one think that an utterly ordinary experience shared by countless others is somehow unique, or uniquely interesting.”

Krauss’s brief might be antifeminist, but subtler minds, Nelson included, have also worried about the intense absorption families induce, and its consequences not just for art but for society. What happens when we funnel the best of ourselves—our attention, time, and resources—only into our children? Virginia Woolf, for one, was appalled by the prospect. In The Years, she has her character North overhear, with some revulsion, parents in conversation: “My boy—my girl . . . they were saying. But they’re not interested in other people’s children, he observed. Only in their own, their own property; their own flesh and blood, which they would protect with the unsheathed claws of the primeval swamp,

he thought.”

On Immunity, Eula Biss’s study of the anxieties surrounding vaccination is, in part, a book about these unsheathed claws—and what havoc they can cause. After the birth of her son, Biss suffered a surge of anxiety; she became consumed by fears of contagions and potential dangers to her child. And she began to listen closely to other mothers, especially those who feared vaccines—a growing number of white, well-educated, well-off women who stalwartly refuse to be swayed by the evidence showing that vaccines are not only safe but crucial for everyone’s safety. Biss traces these women’s terrors to a larger, very American distrust of the collective: “We are locking our doors and pulling our children out of public school and buying guns and ritually sanitizing our hands to allay a wide range of fears, most of which are essentially fears of other people.”

“How then can we be civilized?” asks Woolf’s character in The Years. Biss preaches the gentle doctrine of interdependence: “We are . . . continuous with everything here on earth.” The very cells that bind the placenta, she points out, came to us from a virus. Lerner puts these ideas of interdependence into a poetic kind of practice in 10:04. The narrator, also a poet turned novelist named Ben, allows a young Occupy Wall Street protester to use his shower. While cooking a meal for the two to share, Ben is suddenly seized by the pleasure of taking care of someone. He imagines looking after a child—and catches himself. “Your gesture of briefly placing a tiny part of the domestic—your bathroom—into the commons leads you to redescribe the possibility of collective politics as the private drama of the family,” he reproaches himself in his comically self-serious, hyperprecise way. “What you need to do is harness the self-love you are hypostasizing as offspring, as the next generation of you, and let it branch out horizontally.”

This is what happens, after a fashion; his tenderness radiates across his city. He volunteers at a co-op, mentors a child, and participates in food relief during Hurricane Sandy. He donates sperm to his best friend, Alex, who wants to have a baby. At the end of the novel, Ben and Alex, now pregnant, walk through Manhattan after the storms have passed, Ben delivering a winding, Whitmanesque coda that roves uptown and down, into the city’s future and his own past. He concludes with this assurance: “I am with you, and I know how it is.” Nothing is excluded from this embrace, one feels; he could be addressing “you,” the reader; “you,” the city; “you,” the unborn child. Nothing could be further from the family exclusivity Woolf feared than such expansiveness.

In The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson also imagines enlarging the idea of the domestic beyond the nuclear family to signify “an ethic, an affect, an aesthetic, and a public.” She doesn’t pursue what this might look like—assertion is not her mode, unraveling is—but she shows us the pointlessness of partitioning life from life, of quarantining the domestic from the erotic, from the political. Crucially, she frames family-making, specifically queer family-making, “as an umbrella category under which baby making might be a subset, rather than the other way around.” Family becomes less about the particular relations between people than the acts of devotion that pass between them. (Let us remember that the happiest families in literature—from Dickens to Alison Bechdel’s long-running comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For—have always been the ones people choose, not the ones they make.)

To read so many books about family-making all at once is to encounter startling similarities between some very different writers. Several books repeat a scene: the writer at a public pool or bath staring, with ferocious interest, at the bodies of very old women. Many reach for the same metaphors and are lit by the same obsessions. We encounter a chorus of sorts: “I became a mother. I began to inhabit time differently. It had something to do with mortality.” (Sarah Manguso) “When we talk about mortality we are talking about our children.” (Joan Didion) “I used to exist against the continuity of time.” (Manguso) “I have the curious feeling that I no longer exist in synchronicity with time.” (Rachel Cusk) “I felt like a clock, one made of blood and bone.” (Anne Enright) “I had been fitted with a taxi meter, to which the price of experience is inseparably indexed. When I am out I am distracted by its ticking.” (Cusk) “I don’t understand how time passes.” (Grace Paley) “Time passes. Could it be that I never believed it?” (Didion) It’s as if they’re taking turns uttering some floating truth once it comes to lodge in their particular bodies.

This phenomenon, and this vexed relationship with time, are some of the swirling preoccupations of Manguso’s Ongoingness, an examination of her habit, her “vice,” of obsessive diary keeping. The diary itself, some eight thousand pages long, doesn’t appear in the book, just her riffs on how her relationship to it has changed since the birth of her son, how her memory and attention have been reordered. The diary is her defense against the steady leak of time, against “waking up at the end of my life and realizing I’d missed it.”

What Ongoingness, and the practice of diary keeping, makes evident is that our lives are, in many ways, what we regularly choose to notice, who we choose to look at. The issue of attention burns at the core of all these books—Rachel Cusk examines how it contracts after the birth of a child, Anne Enright how it expands. Sarah Ruhl makes an aesthetic out of how it fractures. Ben Lerner asks if the uniquely intense quality of attention specific to the domestic can be coaxed out of familial bonds and into the public, Maggie Nelson how language helps or hinders our abilities to attend to each other. They all invite us to try to hold a little more in our eye, to define families broadly—out of necessity and joy—to remember, as Eula Biss might say, that they are continuous with everything on earth. “Everything is relevant,” wrote the poet James Tate. “I call it loving.”

Parul Sehgal is an editor at the New York Times Book Review.