On November 18, 1978, more than nine hundred members of Peoples Temple church died in a mass suicide-murder in Jonestown, Guyana. It was a horrific epilogue to the dream of building a socialist utopia in the South American jungle. Jim Jones, the Temple’s charismatic leader, had promised his flock deliverance from America's ills: racism, sexism, capitalism, and economic burnout. Instead, he controlled his city like a police state, enforcing a paranoid regimen of loyalty oaths, suicide drills, and brainwashing. His drug-fueled sermons, beginning in the evening and lasting until 2 or 3 AM, spelled out a doomsday scenario of CIA invasion and torture. “They will not leave us in peace,” he warned his followers, but in the end it was Jones himself, the Temple’s beloved “father,” who rallied his people to their own destruction.

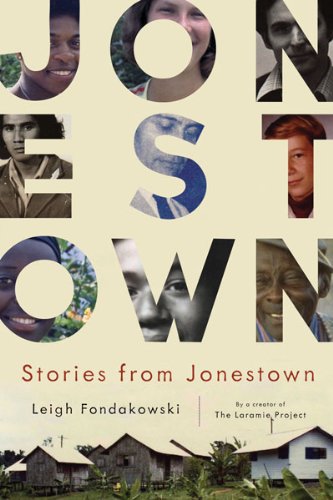

Peoples Temple remains an enigma despite having spawned a cottage industry of books, documentaries, and scholarly studies. The most fundamental misrepresentation is that it was a cult and Jonestown the apotheosis of a collective death wish. Jim Jones, with his painted sideburns and aviator sunglasses, has become a totem of ’70s kitsch, the apocalyptic flipside to Jimmy Carter and Alfred E. Neuman. The truth captured in Leigh Fondakowski’s Stories from Jonestown, a new collection of interviews with survivors of Peoples Temple, is far murkier. Fondakowski, the Emmy-nominated screenwriter behind The Laramie Project, spent three and a half years gathering testimonies for her 2005 play The People’s Temple; Stories from Jonestown is, in her words, “an extension of the life of the play.” That's an apt description not only for the book's polyphonic style, but for the three-act arc of the Temple itself: before, during, and after Jonestown.

Memory is necessarily subjective, but a cohesive picture does emerge from these piecemeal histories, namely a record of American faith circa the ’60s and ’70s. After caravanning from Indiana to the idyllic backwater of Ukiah, California, the forty-one-year-old Jones decided to headquarter his church in San Francisco’s predominantly black Fillmore district. It was a perfect backdrop for the Temple’s gospel of integration and brotherhood, as well as an ideal recruiting station for disillusioned blacks seeking a leftist spin on the old Pentecostal tradition. Many survivors recount converting instantly upon witnessing desegregated worship. As Vern Gosney recalls: “There was music and everyone's dancing, people getting raised from the dead, it was pretty good.”

Then there was Jones himself: “He didn't come out in the traditional dress like a preacher would . . . he came out in a velour shirt, a stripy velour shirt, black pants, black shoes, and these sunglasses. And boy, this bro's cool, you know.” Jones's sermons—which read like a mulch of Huey Newton, government affidavits, and the Book of Job—were reportedly hypnotic. Hue Fortson, a fellow preacher, remembers: “Jones had a way of talking, and he'd take his voice and go up and go down and bring it back around and show you.” Flamboyant displays of stigmata wherein Jones slid a catheter of ox blood under his sleeves only stoked the frenzy. In the words of Laura Johnston Kohl: “Sometimes we were happy, and sometimes we were sad, and sometimes we were politicized—but we were never bored.”

Emboldened by his messianic persona, Jones began extorting sacrifices from his congregation: sex with both men and women, taped renunciations of American citizenship, surrender of social-security and foster-care checks, loyalty oaths in which suicide was the inevitable endgame. In 1977, shortly after local journalists began publishing damning exposés of Peoples Temple, Jones uprooted his church and resettled 4,500 miles away in Guyana. Presented to the Temple's members as a kind of Canaan where they’d finally be free from witch-hunts, Jonestown was actually a scrawl of jerry-built dorms and broken fields, all sapped by equatorial heat and ravaged by rain, fever, and mosquitoes. As Juanita Bogue recalls: “Everybody who got off that truck the first day . . . saw the lie [Jones] had told, they realized what he had did. Now he had full control.”

Not surprisingly, the Temple’s inexorable decay makes for the book’s most riveting chapters, especially when Fondakowski describes watching the final day play out in grainy VHS footage in survivor Tim Carter’s bedroom. The footage, captured by NBC news during Congressman Leo Ryan’s ill-fated tour, is a harrowing testament to human inscrutability. In scene after scene, church members are filmed dancing and laughing while children mug for the camera; hours later, all of them would be dead. As Carter struggles to narrate the day’s unraveling, we become, like Fondakowski, witnesses baffled by how such ebullient, soulful people could destroy themselves. Did they know it would be their last day alive? Could they feel the edginess in the air? A storm blew into Jonestown that last day, and as Fondakowski watches the afternoon darken on videotape, Carter evokes a jumble of chaotic events: The vat of cyanide being rolled out; Jones rustling his flock to the pavilion; mothers squirting poison into their children’s mouths and then swallowing it themselves; hundreds of people, many of them children and teens, lying down to die in the mild November air. One of the most poignant statements comes from Dick Tropp, the Temple’s self-appointed historian, who minutes before killing himself wrote: “We are a long and suffering people. I wish I had time to put it all together—the meaning of a people—a struggle, to find the symbolic and eternal in this moment—I wish that I had done it. I did not do it. I failed. A tiny kitten sits next to me. A dog barks. The birds gather on the telephone wires.”

Anyone who has read Tim Reiterman’s magisterial Raven, Julia Scheere’s A Thousand Lives, or Shiva Naipaul's Journey to Nowhere is already familiar with Jonestown’s countdown to death, but hearing it again, anew, in the words of people who were there has the rawness of a bloodletting. Tim Carter is haunted by his failure to intervene; he watched his wife poison herself and their baby son but did nothing to stop them. He survived thanks to a last-minute order to ferry the Temple’s assets to Guyana's capital. Juanita Bogue, chainsmoking in her shabby Oakland apartment while her son languishes in prison, is another living ghost; Phil Tracy, a reporter who investigated Peoples Temple prior to their decampment to Guyana, is another; Jack Palladino, a former private investigator, is still another. “The real legacy of Jonestown is pain,” Stephan Jones, Jim’s son, remarks, and these interviews corroborate that again and again. At the same time, however, they testify to a deeper and more conciliatory mystery: how people continue to live in the aftermath of tragedy.

“Peoples Temple failed, but the story does not end there,” Fondakowski writes. “The lives of the people who built the movement, and how they have survived, still bear examining.” This echoes the slightly misquoted Santayana aphorism that graced Jonestown’s pavilion: “Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” But it’s also a reminder that truth is a kind of forgetting. Peoples Temple failed not because its members ignored history or the warning signs of a deformed faith, but because they believed in their own ability to subvert those obstacles. They believed themselves to death, and the power of Stories from Jonestown is how it dismantles an epic tragedy into fragile human parts.

This is a book that seeks to set the record straight about the culture and politics of Peoples Temple, and as such is a crucial addition to the Jonestown canon. For perhaps the first time, we hear the voices of the Temple instead of seeing the casualties. We get an indelible sense of the believers' youth and optimism, along with the vulnerability that drove them into the arms of the wilderness. Not all of them killed themselves willingly, but all of them gambled on Jones’s promise of a better life. They gambled on a future where all they had sacrificed would mean something to the world. The tragic irony is that it did.

Jeremy Lybarger lives in San Francisco and works for Mother Jones. His writing has appeared in The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Brooklyn Rail, and Salon.