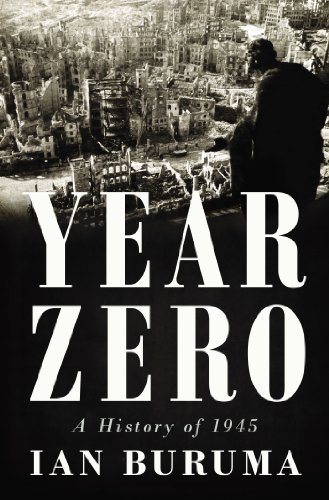

Vichy France was a disgusting place. Harper's readers were reminded of that in the October issue of the magazine, which included an excerpt from a 1945 handbook for American soldiers in occupied France. It featured useful tips on navigating filthy streets (where "the acute shortage of gasoline prevents refuse trucks from making daily rounds"), making do with corroded plumbing systems, and coping with villagers' "malodorous custom of piling manure in front of houses." These descriptions set the stage for Ian Buruma's Year Zero: A History of 1945, which illustrates in harrowing detail how forging a new world order out of the remains of war can be nasty business. One might have expected that the end of World War II would have immediately ushered in a period of international peace. Buruma demonstrates that before it did, the world descended into a brutal free-for-all, full of reprisal killings against religious and ethnic minorities, political disarray, and carnal excess.

What Buruma delivers in Year Zero is a counter-narrative to the widely accepted idea of 1945 as a year of global reconciliation. At the close of the war, the victors were faced not only with the problems of widespread starvation and ruined cities, but also with the task of creating a new political and economic order, and of resolving (or at least learning to manage) old rivalries. Foreign armies were sent to rebuild countries they had been attacking only months earlier. In many cases, the line between exacting revenge and offering assistance was a thin one.

Following the resolution of the war, the world was suddenly divided between capitalists and Communists, and establishing a post-war firmament required both sides to play nice and respect each other's territorial claims. For the most part, they did—Stalin agreed not to meddle with prominent Communist movements in the American sphere of influence in places like France and Italy, and the Allies did the same in regions beyond their sway. But within each side's own territories, old antagonisms persisted: Communists purged those who had aided fascist regimes, and the Americans and British embraced a messianic mission of containing Communism in Europe and the Pacific.

Violence often returned to familiar patterns. The French picked up where they left off in their former colonies, adjudicating harsh, murderous justice to exploding nationalist movements in far-flung places like Algeria and Vietnam. In occupied Germany, anywhere from several hundred thousand to two million German women reported being raped by Soviet troops, and some 240,000 deaths were reported in connection to the rapes. Elsewhere, old antipathies flared up under new political justifications. In a shocking account of violent anti-Semitism in Communist-dominated Poland, Buruma details how Jews returning from the horrors of concentration camps were somehow assumed to still have plenty to plunder and be ardently capitalistic to boot. "Communists were not above exploiting anti-Semitism themselves," he writes, "which is why most Jewish survivors in Poland ended up leaving the country of their birth."

Neither were efforts to re-build the civic and industrial systems of war-torn countries free from the tinge of revenge. In Japan, arch-conservative General Douglas MacArthur and his team of New Deal bureaucrats aimed to stamp out all traces of militarism and feudalism by dismantling the elite business class—the zaibatsu—that had been co-opted by the imperial bureaucracy. MacArthur was out for scalps, and he succeeded spectacularly in the case of the proud General Tomoyuki Yamashita, who had captured the British territories of Malaya and Singapore during the war. In a landmark military tribunal that war crimes scholars continue to grapple with today, Yamashita took the fall for countless atrocities committed by Japanese forces in the Philippines, Singapore, and elsewhere throughout the Pacific.

Throughout the book, Buruma casts a skeptical eye on the notion that 1945 marked a new era of peace. He argues that in many cases, restoring structure meant re-imposing the ruling order of wartime. In Germany, Nazis were frequently let off the hook with a mere slap on the wrist. Ex-Nazi industrial titans like Baron Georg von Schnitzler, Alfried Krupp, and Friedrich Flick all served time in prison for crimes like "plunder and spoliation," but they also received shortened sentences, after which they all resumed their business ventures without much fuss. This was not ideal, but as Buruma tells it, many American officials felt it was the only option. "You couldn't really gut the German elites . . . and hope to rebuild the country at the same time, no matter whether that county was to be a communist or a capitalist one," Buruma writes, adding that the Allies quickly came to see "economic recovery as a more important aim than restoring a sense of justice." General George Patton even compared the Nazis to American political parties, reportedly saying that "we will need these people" to help rebuild the country and restock the government. (For that remark, he was fired from his post as military governor of Bavaria.)

As 1945 drew to a close, the global elite—primarily leaders of the US, UK, and reconstituted France—struggled to contain the violence, rebuild, and understand how things had fallen apart in the first place. They helped launch international initiatives like the International Monetary Fund to stabilize the global economy, and the United Nations to police the world. As the past seventy years suggest—witness the global financial crisis and genocidal atrocities in Rwanda, the Balkans, and elsewhere—their records are decidedly mixed. Buruma argues that efforts at peaceful internationalism, though well-intentioned, have been overshadowed by a "seemingly unassailable American hegemon" that continues to bumble its way forward as the most powerful economic and military force the world has ever seen. Still, the world has not experience a third world war. And as Buruma makes clear, that is no small feat.

Buruma's tone in the soberly drawn and meticulously researched Year Zero is often clinical. But when he sheds that voice for something more visceral, the effect is unsettling, aptly capturing the depths of absurdity wrought by chaos. Written for his father, who worked in a Nazi labor camp during the war, the book suggests that even our best efforts cannot guarantee that the worst of all possible outcomes will not be revisited, time and again.

Siddhartha Mahanta is a writer living in Washington, D.C. He has written for a range of publications, including Mother Jones, the New Republic, and the Atlantic.