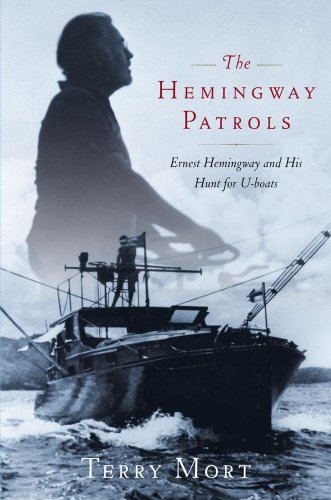

When the United States declared war on Germany and Japan in 1941, Ernest Hemingway did not immediately travel to Europe as a journalist, as he had for the Spanish Civil War. Instead, he stuck around Havana, where he drank (Scotch and sodas, daiquiris) and went fishing. In a grandiose and ultimately ineffectual manner, he also devoted time to the Allied cause, hunting enemy submarines in a wooden fishing boat called the Pilar.

Hemingway’s biographers have largely ignored this period in his life. Kenneth S. Lynn, for instance, devotes just two pages to the U-boat gambit in his nearly six-hundred-page life. In The Hemingway Patrols, however, Terry Mort breaks with tradition by giving full treatment to the author’s Cuban wartime activities, which ranged from the summer of 1942 to the end of 1943. Although Mort wagers that this episode merits close attention, he only succeeds in illuminating why no one has bothered to give it consideration before.

He concedes that Hemingway’s strategy was almost comically bad: The writer planned to troll around the Gulf of Mexico with a small crew until stopped by a U-boat, then shoot at the steel hull with handheld machine guns and maybe toss a grenade into the conning tower. It’s lucky Hemingway never actually tracked down a submarine (although he insisted he’d sighted one at a distance), because he almost surely would not have survived the encounter. But Mort is ultimately less interested in the feasibility of Hemingway’s operation than in what it reveals about his personality. Hemingway, Mort argues, knew that his patrols were dangerous but persevered because he wanted to “be the hero of his own life, to become one of his characters.” Francis Macomber against the wounded buffalo, perhaps, or Manuel Garcia versus the bull.

This interpretation, a rather grand one, is undercut by that of Martha Gellhorn, Hemingway’s wife at the time. In her view, Hemingway realized early on that the Germans weren’t interested in the dinky Pilar, and she claimed that his cruises were merely an excuse to fish—an opinion seconded not only by the lone Cuban national to actually sink a U-boat, Captain Mario Ramírez Delgado, who once called Hemingway “a playboy who hunted submarines off the Cuban coast as a whim,” but also by the fact that the writer occasionally took his young sons along.

Mort tries to lend dignity to these fruitless proceedings by arguing that they influenced Hemingway’s creative work. Here, too, Mort’s analysis is less than stellar, either stating the obvious or reaching too far. The time Hemingway thought he sighted an enemy sub, Mort argues, inspired a conversation about such an incident that appears in Islands in the Stream (a posthumously published novel written largely in 1951). This is patently clear and, therefore, banal—like pointing out that Hemingway’s experience driving ambulances during World War I informed his characterization of ambulance-driver Frederic Henry, the protagonist of A Farewell to Arms. Somewhat fishier is the suggestion that the marlin in The Old Man and the Sea (1952) bears a resemblance to U-boats. Hemingway does compare the fish’s eye to “mirrors in a periscope,” but this doesn’t offer conclusive evidence of a connection, especially since he mapped out the basic idea for the story as early as 1939.

The title of Mort’s epilogue, “The Meaning of Nothing,” doubles as a summation of his thesis: Although nothing happened on the patrols, they’re nonetheless significant for being “representative of the man and his many facets,” of his desire to “confront the unknown.” Hemingway may initially have believed he could help the war effort, but given his half-baked battle plan and the dismissive assessments of those who knew him, it’s likely that the author attached little importance to his boating trips. In view of that, a more apt heading might have been “Much Ado About Nothing.”

Juliet Lapidos is an assistant editor at Slate.