They called her the Queen of Kings. She built a kingdom into a mighty empire that stretched down the shimmering eastern coastline of the Mediterranean. She married—and murdered—her two younger brothers. She bankrolled Cesar and Antony and bore them both sons. She was worshipped as a goddess in her lifetime. She was lithe and darkhaired. She was not beautiful.

The scribes of her time were awestruck by her wit and money, never by her face—she was no Olympias, no Arsinoe II. The coin portraits she issued, our most accurate depictions of her, reveal a beaky little thing with a wide mouth and avid eyes, looking rather pleased with herself and resembling, of all people, Saul Bellow.

Why then this curious conspiracy (from Plutarch on) to recast Cleopatra VII, who lived from 69 B.C. until 30 B.C., as a great beauty? To market her—she who slept with only two men in her 39 years—as an insatiable sexual savant? (That the men in question were Julius Caesar and Mark Antony seems to speak more to her political ambition than any wantonness.) Why has this pragmatic and unprepossessing stateswoman been reduced to “the sum of her seductions?”

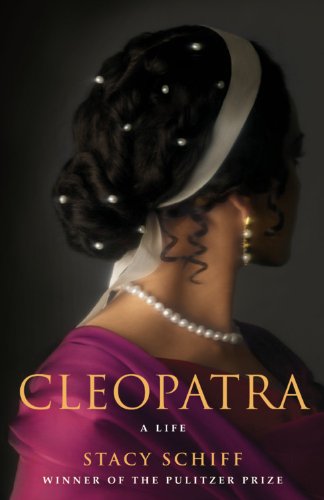

In her latest book, Stacy Schiff, the Pulitzer prize-winning biographer of Véra Nabokov and Benjamin Franklin, plucks at this riddle and what she discovers—about Cleopatra and the men who made her myth—is astonishing. To understand Cleopatra is to understand how ancient history was written, by whom and for whom, and why.

But first, Schiff must match her pen against the mischief-makers: Cicero and Horace, Shakespeare and Shaw. Artists from Boccaccio to Brecht have had a go at Cleopatra: Dio made her simper, Dante plopped her in the second circle of Hell (her sin: lust), Michelangelo coiled snakes around her throat. She’s been distorted in sculpture, on the stage, made everywhere the pin-up girl for female faithlessness, guile, and corruption.

Schiff hacks through myth, “the kudzu of history,” to search for the real woman. It’s a formidable task—no papyri from Alexandria survive and other “lacunae are so regular as to seem deliberate.” Schiff’s is therefore a ginger history, a model of circumspection. Ready to leave the “irreconcilable unreconciled,” she fills in the gaps with texture and context, careful speculation on places the queen would have been likely to go, duties she might have performed.

A large—perhaps too large—swathe of the book is steeped in the conditional. Still a portrait emerges of a Cleopatra we’ve yet to meet: less lurid, but no less compelling. Rather like Indira Gandhi or Benazir Bhutto, this daughter of a political dynasty was initiated quickly and brutally into her office and evinced an appetite for butchery all her own. She was an uncommonly gifted leader: a Greek who brought peace and prosperity to a nation of Egyptians, Syrians, Thracians, Buddhists, and Jews. She was the descendent of powerful Ptolemy queens, zoologists, playwrights, who presided over Alexandria, that “first city of civilization” where anatomy was discovered and geometry imagined. She was not beautiful but she was resourceful, glib, and very clever. And if clever women are dangerous—as Euripedes liked to remind us—a woman rich and clever are often intolerable, especially in Rome, which shared none of Alexandria’s enlightened views toward women (according to Schiff, Roman women “enjoyed the same legal rights as infants and chickens”).

Rome abhorred her. She was the preening queen from the East, the richest person in the known world who snagged first Cesar, then Antony. Egypt’s coffers kept Rome running, and Cleopatra’s high-handedness and taste for pomp kept its citizens feeling shabby and captious. Cicero never forgave her. Octavian saw to it that coming generations never would.

How better to rally an exhausted kingdom to war than by playing on existing antipathies? Convincing his populace that sex-struck Antony would hand over Rome to his mistress, Octavian invaded Egypt and the Romans took control of the story, writing her defeat even as she fought desperately fortify Alexandria.

Already the death mask—those rumors of dangerous beauty—was being prepared to fit over the plain face of an extraordinary woman. “It is less threatening to believe her fatally attractive than fatally intelligent,” Schiff writes, and this sober account peels away the exaggerations, be they romantic or vindictive, revealing how this profoundly threatening figure was domesticated, how her vast powers reduced to mere prettiness.

This is not to say that Schiff has sapped the drama from the story. Our introduction to the young queen is unforgettable: twenty-one-year old Cleopatra, recently orphaned and exiled, stands under “the glassy heat of the Syrian sun.” Her brother has stolen the kingdom they were meant to rule together. Twenty thousand of his men move towards her from the East. In the windswept desert, she assembles a ragtag army with apparent calm. “The women in her family were good at this and so clearly was she,” write Schiff matter-of-factly, even as this indelible image of the focused young warrior-queen rocks our every preconception about Cleopatra. And even if her partnerships with Caesar and Antony were very likely mutually advantageous political alliances and not the grand passions of the legends, her romance with Antony—their pranks and play and inseparability—still delights.

Still, it must be admitted, that we see the queen at a remove, always; intimacy is impossible. Her voice is mostly missing. It’s the people who wrote her story—the Page Sixers and propagandists of Cleopatra’s day—whose (generally questionable) motivations have been most thoroughly explored. Even as we might rue how elusive Cleopatra proves, it’s a piquant pleasure for a biography to so clearly affirm the power of the genre—to demonstrate that possessing the shimmering eastern coastline of the Mediterranean is very fine, but that possessing a good biographer is true security. For 2,000 years, Cleopatra has counted “among the losers whom history remembers, but for the wrong reasons.” Schiff’s remarkable book makes a mighty restitution and gives the vanquished queen, finally, a happier afterlife.

Parul Sehgal is a nonfiction editor at Publishers Weekly.