Adam Thirlwell

A narrator is a much stranger toy at the novelist’s disposal than is usually thought. It’s not just something as depressingly ordinary as a character—more a vast system of smuggling. And there’s one kind of narrative voice or tone in particular that offers a way to explore that difficult relationship at the hidden center of every art form: the one between writer and reader (or spectator). Although this tone seems to exist most easily in novels, it isn’t only to be found there—it appears wherever anyone tries to figure out what a monologue might mean, or how to talk to

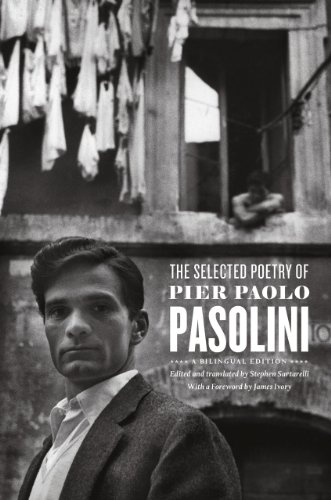

In 1970, five years before he was murdered on a beach near Rome, and about a decade after his first movie, Accattone, had made him notorious as a filmmaker, Pier Paolo Pasolini sat down to write a preface to a new book of his selected poems. He called this little essay “To the New Reader,” and in it he wanted to explain to this new reader—who perhaps only knew him as a filmmaker, or novelist, or polemical essayist—why he was always, in fact, a poet. His first poem, he observed, was written when he was seven. His first collection had