Adam Wilson

JORDAN CASTRO FIRST CAME across my radar in 2011 when he live streamed himself “earnestly” attempting to detach his penis from his body with his bare hands. At the time, Castro was an eighteen-year-old poet and contributor to HTMLGiant, the blog/discussion board where the alt-lit scene bloomed. I remember watching through cracked fingers, unsure if […]

IF THE MEASURE of a debut is how capably it shits on the pieties of its literary forebears, then Honor Levy’s funny, provocative My First Book is an unqualified success. The fact that I, an Elder Millennial, found it largely inscrutable proves the point. Though nominally fiction—at least according to the metadata—the sixteen pieces collected […]

ON APRIL 12, Joyce Carol Oates, who’s had a surprise second act as a social-media provocateur, tweeted, “Much prose by truly great writers (Poe, Melville, James) is actually just awkward, inept, hit-or-miss, something like stream-of-consciousness in an era before revising was relatively easy.” Like much Tweeting by truly great Tweeters, Oates’s hot take struck a nerve because it reflected the zeitgeist; whatever one’s feelings about the nineteenth-century masters, one must concede the current vogue for tightly structured novels, rendered in lucid, well-modulated prose. For a long time now, American fiction has not been characterized by any one school or approach,

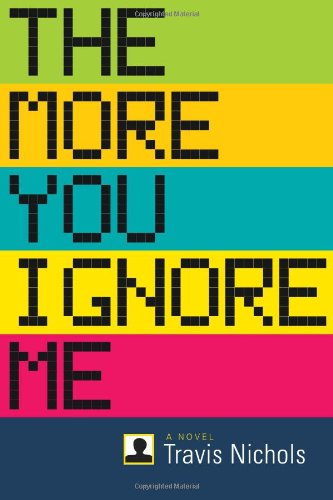

THE STORY GOES THAT ONLY FORTY PEOPLE attended the Sex Pistols’ first concert, but each of them went on to form a band. A similar thing might be said of Tao Lin; his first few books had small readerships, but those who read them went on to write their own plotless, autobiographical novels in which emotionally stunted twentysomethings communicate on their laptop computers via Gmail chat. Lin’s early style was deceptively simple, a robotic deadpan marked by an absence of figurative language and a lack of abbreviations (always “laptop computers,” always “Gmail chat”) that captured a particular strain of millennial

In 2008, Gary Lutz gave a lecture called “The Sentence Is a Lonely Place,” a transcript of which was later published in The Believer. The lecture outlined Lutz’s approach to short stories, specifically his punctilious focus on the sonic qualities of the sentence. He spoke in favor of “steep verbal topography, narratives in which the sentence is a complete, portable solitude, a minute immediacy of consummated language—the sort of sentence that, even when liberated from its receiving context, impresses itself upon the eye and the ear as a totality, an omnitude, unto itself.” Interest in The Complete Gary Lutz, a

There’s a special place in the annals of the epistolary novel for books whose epistles lie dormant in the dead-letter office, unanswered. In Sam Lipsyte’s Home Land, Lewis Miner’s updates sent to his high school’s alumni newsletter, complete with grandiloquent descriptions of his masturbation techniques, are deemed unpublishable by its editors; in Letters to Wendy’s, it’s unlikely that Joe Wenderoth’s unhinged and occasionally pornographic prose poems to the fast-food chain—written on “Tell Us What You Think” postcards provided at the restaurant—reach their destination; in Saul Bellow’s Herzog, the eponymous narrator writes his pained missives but never actually sends them. These

Describing Joshua Cohen’s wonderful and elliptical novel A Heaven of Others is a bit like attempting to rehash an acid trip—no analysis can quite do justice to the feel of the experience. The premise: Jonathan Schwarzstein, a young Israeli boy, is blown up by a suicide bomber, and accidentally martyred into Muslim heaven. The setting: Paradise, the one that rings with the warm cries of infinite deflowerings and runs red with rivers of virgin blood. The prose: an incantatory dream speak—rhapsodic, uber-allusive—that gives the illusion of syntactical chaos, even as it’s stealthily held aloft by an elaborate structural architecture. The Libidinous readers are doubtlessly familiar with Philip Roth’s liver-lubed onanists, John Updike’s man-boys with their dangling modifiers, and the spank-happy secretaries who populate Mary Gaitskill’s fictional universe. Perhaps you’ve traced the lineage of literary eros back to, well, Eros, as rendered by Aristophanes, Catullus, Ovid and the like. And then pushed forward, making pit stops at all erotic poles: Sade, Lawrence, Bataille, Duras, Salter, Winterson, Acker, and Baker (author of the new “book of raunch” House of Holes). But sex is a tireless subject, infinitely engaging. There’s always more to consider, more to discuss, and ultimately more to have. Below

Everyone knows you can’t judge a book by its cover, but what about judging one by its author photo? Surely something can be inferred from an author’s surly eyebrows, or his affected stare into sunset? I bring this up because the author photo for Nicholson Baker’s latest novel, House of Holes: A Book of Raunch, so perfectly captures the book’s warmly horny voice. Baker—chub-cheeked, twinkle-eyed, sporting a Floridian sun-hat and snow white Santa beard—calls up a gentler Hemingway, less Old Man and the Sea than Old Man and the Giant Bottle of Viagra. He looks like a randy but harmless In a recent interview, Grace Krilanovich revealed that she mapped out the story line of The Orange Eats Creeps, her first novel, by drawing cards at random from a homemade deck. This explains, at least in part, the chaotic energy behind this beautiful and deranged book, in which a nameless teenage vampire travels through Oregon in the early 1990s, doing drugs, searching for her missing foster sister, going to hardcore shows, and preying on men when they aren’t preying on her. The narrator claims to have ESP and spends much of the novel channeling Patty Reed, the young Donner Party