Andrew Meier

Kabul in the summer of 1996 was under siege. A little-known force of young militants had surged north from their base in the south. For months, they had camped just beyond the city limits, raining shells on the capital almost daily. They called themselves religious “students”—or in the local Pashto, Taliban. In the final days of the Soviet Union, when the old icons were fast decaying and any future ones were frantically packing off to escape the ruins, the guardians of Russia’s past had few relics to showcase. One of the last heroes standing, a Stalin Prize winner and two-time Hero of Socialist Labor, was Mikhail Kalashnikov, designer of the world’s most famous automatic rifle, the AK-47. Even after the USSR fell, Kalashnikov—now ninety—has enjoyed an afterlife as a living monument to the days when the Kremlin’s fiat reached from Eastern Europe to Southeast Asia and well into Africa. With characteristic

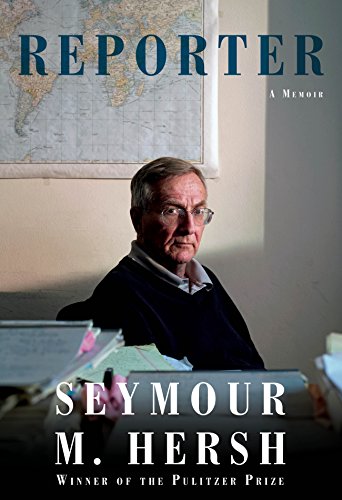

A “Sy Hersh piece,” as readers of the New York Times and the New Yorker have come to know over the past half century, is often met with dread. A dense intrigue unfolds, the unpacking aided by unnamed spooks who unspool salacious quotes, in seeming competition with one another, while the stakes for the body politic build to fever pitch. The tales are arcane, obtuse, and, above all, dark.