Barry Schwabsky

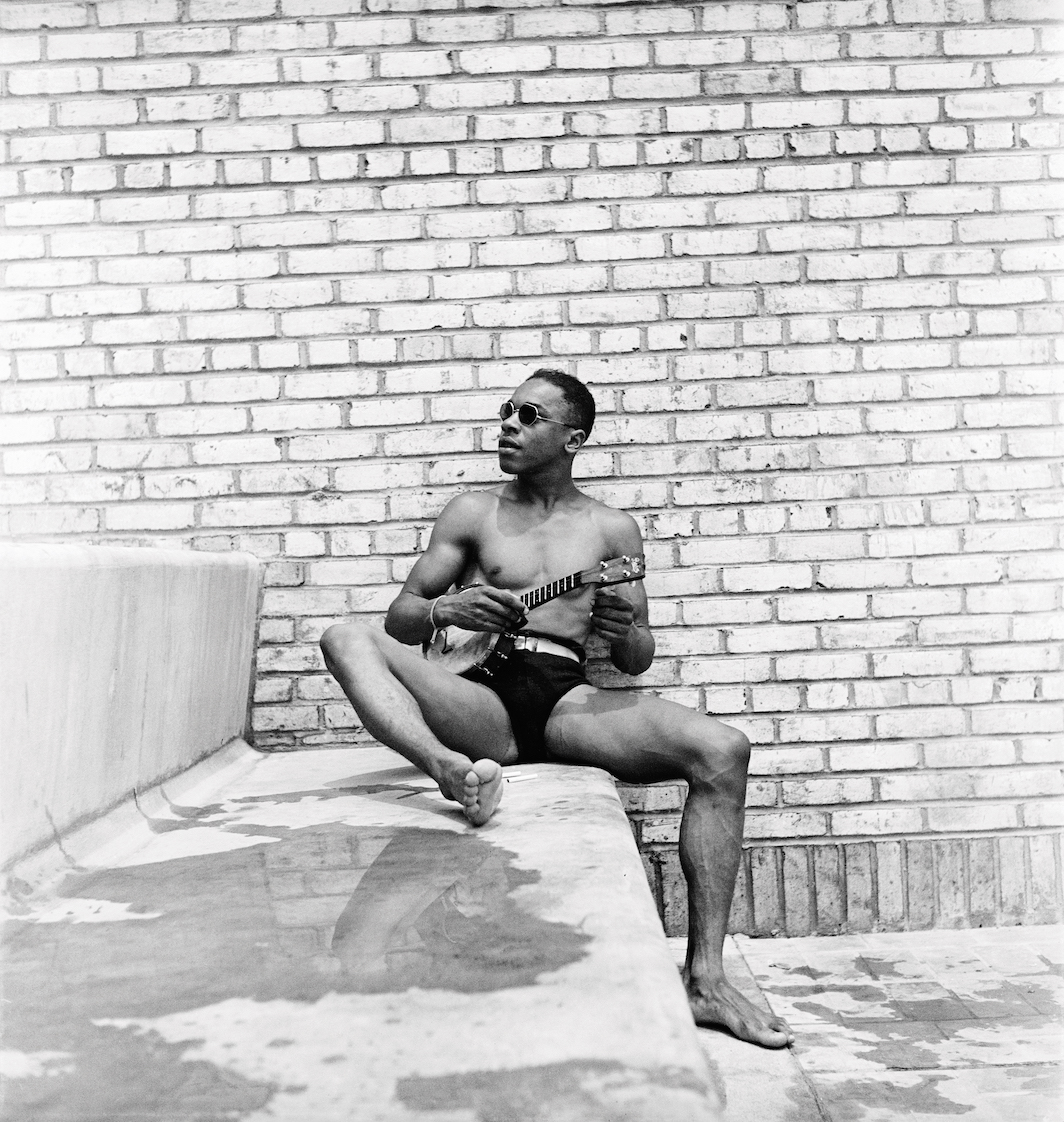

Pierre Fatumbi Verger, Colonial Park Pool, Harlem, New York, 1937. © Pierre Fatumbi Verger BORN IN 1902, Pierre Verger became a successful photojournalist in his native France, in 1934 cofounding an agency whose members included the likes of Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson. He lived mainly in Brazil from 1946 until his death fifty years later, […]

Catalogue page featuring four Jens Risom pieces, 1952. © Jens Risom/FORM Archives IF FRENCH MODERNISM IS RATIONAL, Italian modernism sensual, German modernism ideological, and Danish modernism comfortable, what’s American modernism? I’d say it’s Danish. That’s because of Jens Risom, the Danish-born and -trained designer who, twenty-three years old on the eve of World War II, […]

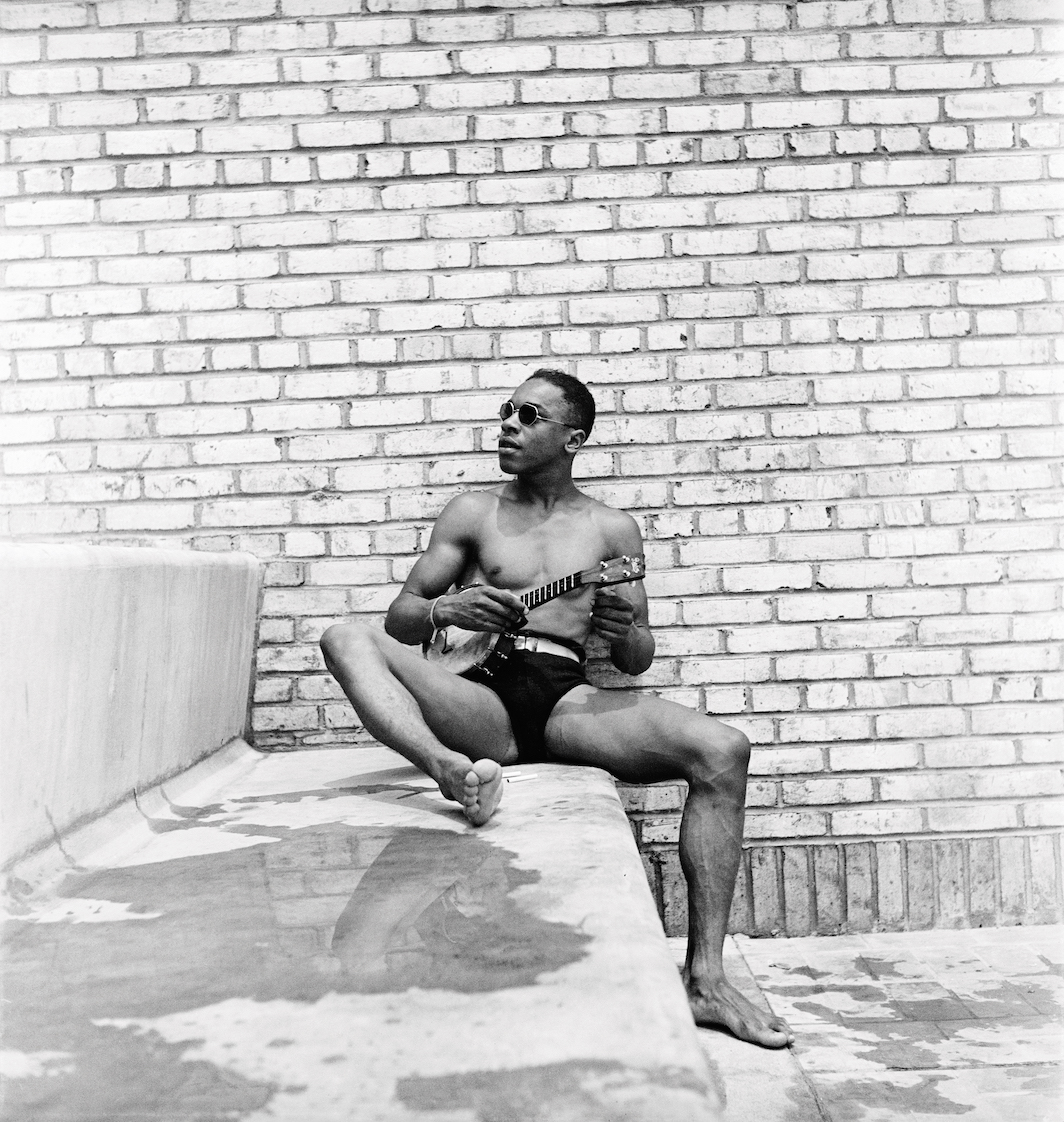

Princeton English professor Jeff Nunokawa has five thousand Facebook friends. I am one of them. If you are one of the other 4,999, it may be because you know his scholarly writings, such as The Afterlife of Property (1994) or Tame Passions of Wilde (2003). More likely, though, you’ve been drawn in by the brief, sometimes enigmatic meditations—Nunokawa calls them essays—he has been publishing daily on the social-networking site since 2007, a selection of which he’s now gathered in print as Note Book. The structure of Nunokawa’s daily entry is usually fivefold: a numbered title, followed by a quotation, often

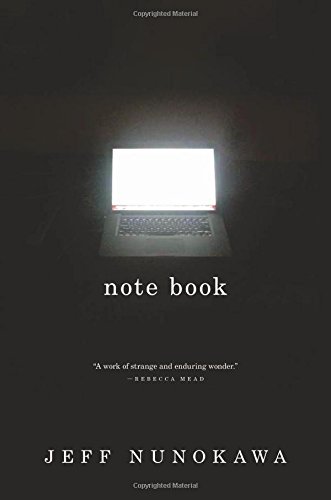

Unheard melodies are sweeter, proposed John Keats, and Craig Dworkin, it seems, can only agree. In his new book, No Medium, Dworkin, a poet and critic who has been among the most active proponents of “conceptual poetry,” treats silent scores and mute records, books with blank pages, white canvases, erased drawings, and other such “foster-children of Silence and slow Time.” He considers, among many other works, Robert Rauschenberg’s “White Paintings” of 1951, Aram Saroyan’s untitled 1968 publication of a ream of blank typing paper, and Tom Friedman’s 1,000 Hours of Staring, 1992–97, an unmarked sheet of paper whose title, as John Baldessari with plaque from Cremation Project, 1970. Trying to make art creates a host of problems. One of the best ways of handling these, as John Baldessari seems to have realized in the mid-1960s, is to let the problems be someone else’s. Then art becomes like the news. “I just read it and laugh,” […]

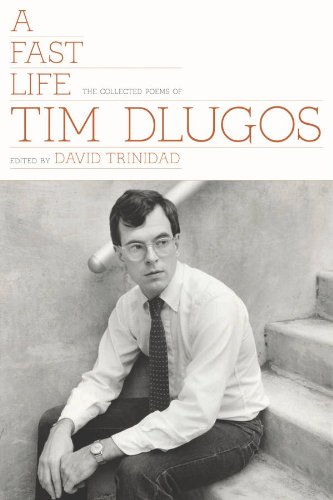

It might seem, on opening A Fast Life, that Tim Dlugos was born fully formed from the head of Frank O’Hara. Dlugos was undeniably an original, but his sophistication and finesse—acquired while he was still a student at La Salle College and immersing himself in the work of the New York School poets—showed from the very beginning, when he started writing at the age of twenty in 1970. His collected poems reveal no big stylistic breaks, no eureka moment when the poet turns the corner from juvenilia to maturity, but rather a continuous deepening of a consistent aesthetic. His life,

“Erase often, if you hope to write something worth rereading,” quoth Horace. Modern authors, perhaps under the influence of the Duchampian concept of the readymade, have been using their erasers in ways the old Roman could never have imagined. Subtractive composition has become a genre of its own in recent decades, its early major examples (in English at least) being the British artist Tom Phillips’s A Humument, derived from an otherwise forgotten late Victorian novel called A Human Document—the first of several versions of Phillips’s book was published in 1970—and the American poet Ronald Johnson’s poem Radi Os, distilled from