Christine Smallwood

CONSTANCE DEBRÉ’S autobiographical novel Playboy is the story of a metamorphosis. We meet the narrator just after she has left her husband, Laurent, and started dating and having sex with women. She had been with Laurent for fifteen years. They were both bored the entire time. The boredom was “a solid foundation,” “a bomb shelter.”

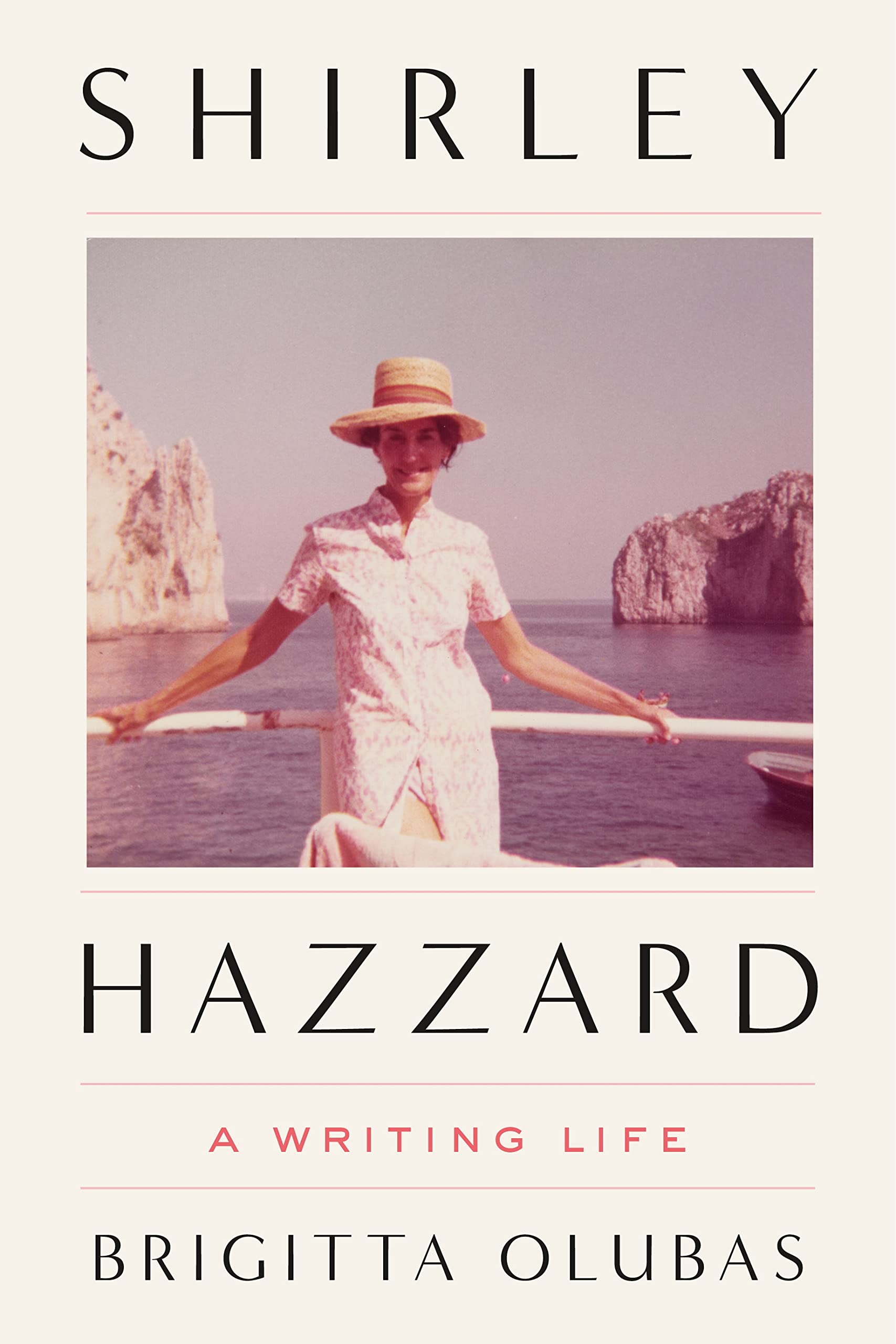

SHIRLEY HAZZARD WAS BORN in Sydney, Australia, in 1931. She was the second daughter of Reg and Kit, who met while working in the office of the engineering company that built the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Theirs was a marriage marked, as Brigitta Olubas puts it in Shirley Hazzard: A Writing Life, by an “almost lifelong incompatibility” made more difficult by Reg’s alcoholism and Kit’s bipolarity. Shirley was Kit’s favorite. When she was six or seven years old, Kit asked her to come to the kitchen so they could together put their heads into the gas oven. Shirley later said that the

THE NARRATOR OF SIGRID NUNEZ’S NEW NOVEL, What Are You Going Through, is an unmarried female writer who seems to be between sixty and seventy years old. She has a friend, another unmarried female writer of the same age, who is dying of cancer. (The friend prefers the word fatal to the word terminal—“Terminal makes me think of bus stations, which makes me think of exhaust fumes and creepy men prowling for runaways,” she says.) After the last round of treatment fails, the friend—no one is named, which works well in the novel but is already cumbersome in a review—invites

Jenny Offill’s first novel, Last Things, was narrated by an eight-year-old girl named Grace. Grace’s mother, Anna, starts out a little crazy, the kind of intellectual eccentric whose home-school curriculum consists of a room painted black and a “cosmic calendar” marking out the origins of life, and then she gets a lot crazy—driving naked, insisting on picnicking inside a burned-down restaurant, that kind of thing. On Anna’s thirty-fifth birthday, mother and daughter bury a time capsule filled with photographs. “The box was made out of a special kind of metal that could survive any kind of disaster known to man,”

My relationship with D. H. Lawrence began in high school, when I bought a copy of Sons and Lovers more or less at random and proceeded to read it all the way through, by which I mean that my eyes literally traversed every page and recognized that the English language was there recorded in some complexity. But the words, instead of building a reality I could enter and move around in, were like a continually dying fluorescence. I had no idea what was going on. What registered was something like “words, words, flower, sentence, words, coal mining” (like I knew In 2009, after his show “Sade for Sade’s Sake,” Paul Chan took a hiatus from making art. He used his time away to found Badlands Unlimited, a press that has since published Saddam Hussein’s On Democracy, Calvin Tomkins’s interviews with Duchamp, dozens of artist e-books, a “digital group show” called “How to Download a Boyfriend,” and one engraved sandstone. In 2015, Badlands started putting out erotica under the imprint New Lovers. “Art is what I do now to pass the time while editing erotic fiction,” Chan told the Paris Review. He says he was inspired to launch New Lovers by

A novel is not designed to be read in one sitting. A reader finds herself in different moods, and different chairs, over the course of a novel; its pages become saturated with meals and conversations and days good and bad. A short story is read all at once, and alone. It might get knitted into life if it is reread many times over the years, but it always arrives complete, a thing apart and sufficient unto itself, like an asteroid. It is at once smaller and more vulnerable than a novel, and stranger and stiffer, somehow more independent. It doesn’t

When Lydia Davis won the 2013 Man Booker International Prize, the attempt to fix a label to her work reduced one of the judges, professor Sir Christopher Ricks, to a bit of flailing. “Lydia Davis’s writings fling their lithe arms wide to embrace many a kind,” he fretted. “Just how to categorize them? Should we simply concur with the official title and dub them stories? Or perhaps miniatures? Anecdotes? Essays? Jokes? Parables? Fables? Texts? Aphorisms, or even apothegms? Prayers, or perhaps wisdom literature? Or might we settle for observations?” Personally, I’m not sure what the problem with just calling her

It took the American novelist Lionel Shriver a long time to get our attention. Her first six books, published in the course of two decades, were met with a critical shrug and sales that Shriver later described as “in the toilet.” Her seventh, an epistolary novel narrated by the mother of a school shooter, was rejected by thirty publishers before a small house in England (Shriver’s adopted homeland) paid her all of two thousand pounds for the manuscript. In Chris Kraus’s novel Torpor (2006), the protagonist Sylvie remarks to an all-male group of intellectuals, including her husband, that there are no women on the list of writers they’re putting together for a cross-cultural literary tour. No one knows any of the “dowdy” lesbians that Sylvie has put forward, so they settle on Kathy Acker. There is little debate. “Of course, thinks Sylvie, if there has to be a woman, Acker would be it. Her books seduce and challenge heterosexual men; her photos just seduce them. . . . Why could the famous artist men be friends, the women