Emily Cooke:

Clancy Martin first proposed to Amie Barrodale, his third wife, outside a New York Barneys, ten days after they’d met and just after buying her a $525 Pamela Love bracelet that she’d requested for her birthday. Martin was less rich than Amie had fancied, but he was willing to spend. Later he proposed again, at a Mexican restaurant, with one eye on the bar (alcohol was a love with a longer history). On a Kansas City sidewalk he proposed a third time. Amie said yes on every occasion. They decamped to India to be married by her guru, and there—either

In 1976 Lore Segal published a short, fabulist satire of literary New York, narrated by a wide-eyed poet, Lucinella, who charges from one party to the next, directing her considerable wit cruelly inward, at her own ambitions and doubts, and affectionately outward, at her striving intellectual friends. In its brevity, its free handling of time, and its lightheartedness, Lucinella almost resembles Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, while the clipped narrative rhythms and wry high-low style bring to mind Grace Paley. The talk is emphatic, exclamatory. The characters’ last names are silly (“Winterneet,” “Betterwheatling”), and the humor tends toward exaggerated self-deprecation. Profound themes—the Trinie Dalton Trinie Dalton excels at characters who live and think inexpertly. The main narrator of her 2005 debut collection of stories, Wide Eyed, has bad judgment, isn’t fazed by strange or implausible events, and believes (or wants to believe) in things a skeptic would call woo-woo: talismans, ghosts, mystical signs. Baby Geisha, Dalton’s new […]

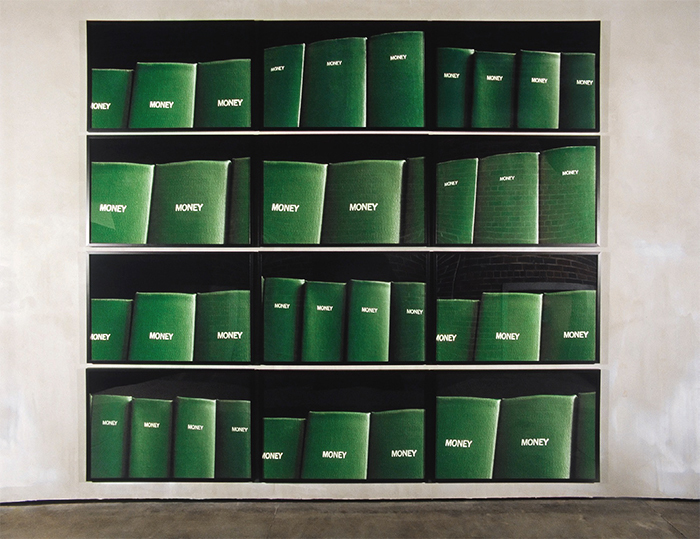

There was a moment soon after I moved to New York City from Oregon—though not that soon, maybe two years in, the point being how long my pristine naïveté resisted corruption—when I realized that every new literary person I met had gone to Harvard or Brown. I didn’t know why more of them hadn’t gone to Yale, Princeton, or Cornell (my new friends, with their firsthand understanding of the relative strengths of the Ivies, likely could have explained), but they hadn’t. These people had been, as a rule, editors of the Harvard Advocate or tutors at the Brown Writing Center,