Gary Indiana

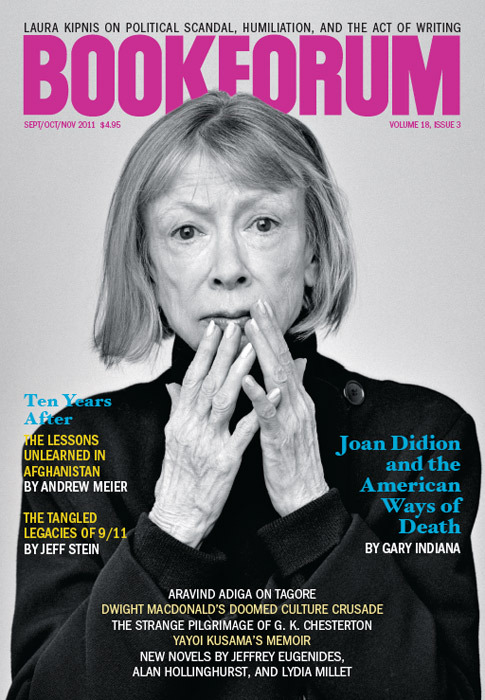

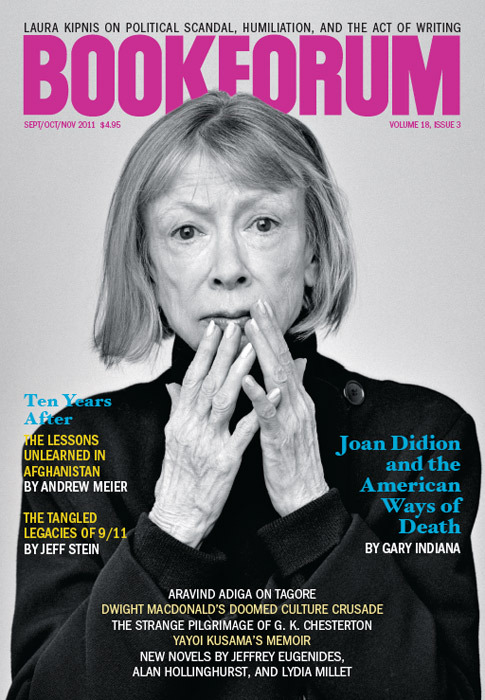

This week, the editors of Artforum and Bookforum remember Joan Didion, the peerless American novelist and essayist. Her canonical work was capped in 2011 by the memoir Blue Nights, which Gary Indiana considered for Bookforum alongside Susan Jacoby’s Never Say Die: The Myth and Marketing of the New Old Age. His essay is an uncompromising polemic about aging and death—and why we shouldn’t look away.

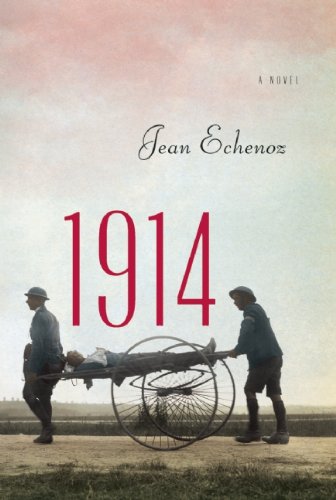

In several recent novels the succinct, startling prose of Jean Echenoz has achieved the condition of a highly durable, transparent membrane, something like the trompe l’oeil mesh often used now to mask scaffolding on building facades under repair. Imposing a Beckettian principle that drastically less is immensely more, Echenoz summons a fulsome picture of his characters and their worlds with a scattering of surgically exact, granular details both irreproachably veracious and wildly defamiliarizing, such as the swarm of mosquitoes that attacks the protagonist of I’m Gone (1999) as his dogsled approaches the Arctic Circle: Yes, there is a mosquito problem

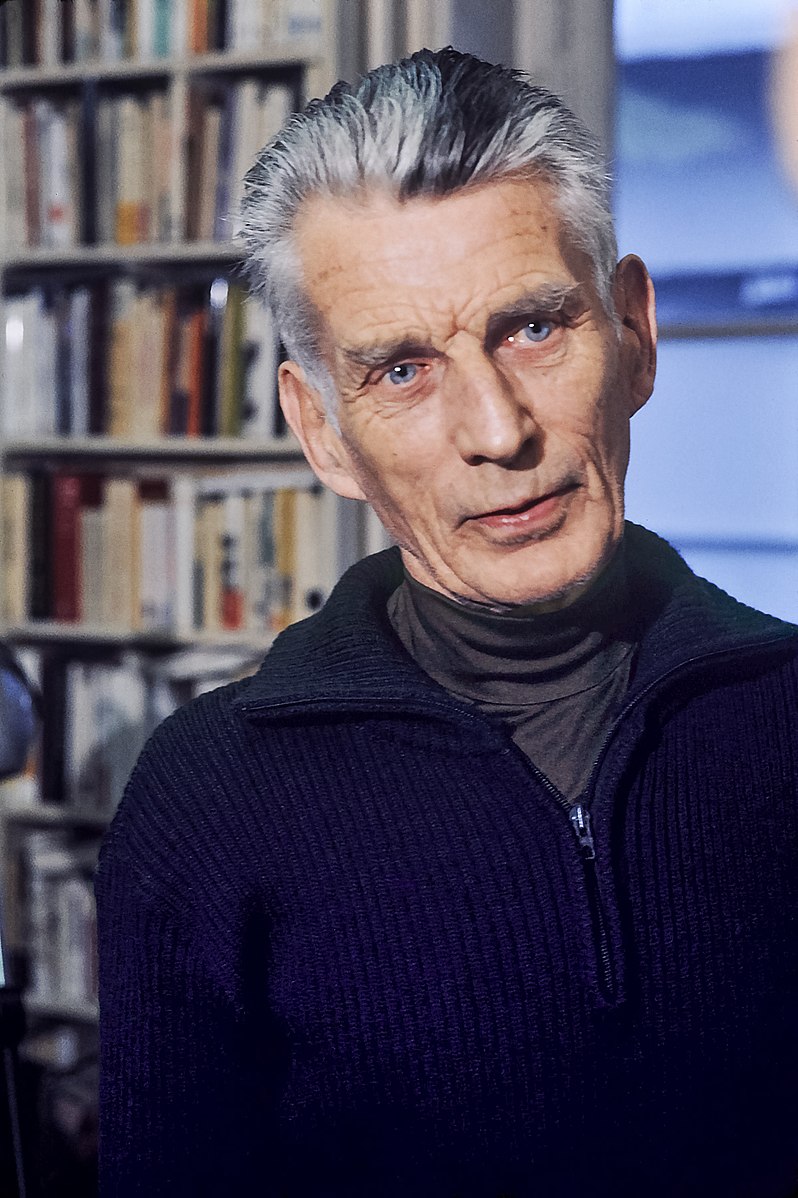

The Letters of Samuel Beckett, 1941–1956, volume 2 of a projected four-part compendium, is an endless Chinese banquet at which all but the most determined gourmands are likely to feel stuffed somewhere between the crispy pig ears and the thousand-year eggs: Some may thrill to the hairpin turns and daredevil high jinks involved in the translation of Molloy from French into English, but many with more than a glancing interest in Beckett may find by page 200 or so that his correspondence and its staggeringly detailed footnotes have, to torture a phrase from Jane Austen, delighted them quite enough for Laura Trombley’s Mark Twain’s Other Woman and Michael Shelden’s Mark Twain: Man in White are remarkably absent any close study of the literary works of Mark Twain, concerned as they are with the last decade or so in the life of a writer whose important books had been written very previously. Twain’s major project between 1900 and 1910 was the burnishing of his public image; as his every sneeze, utterance, and physical movement from one location to another was clocked for posterity by the world press, typically in banner headlines, the historically ill informed could easily conclude that the period