Howard Hampton

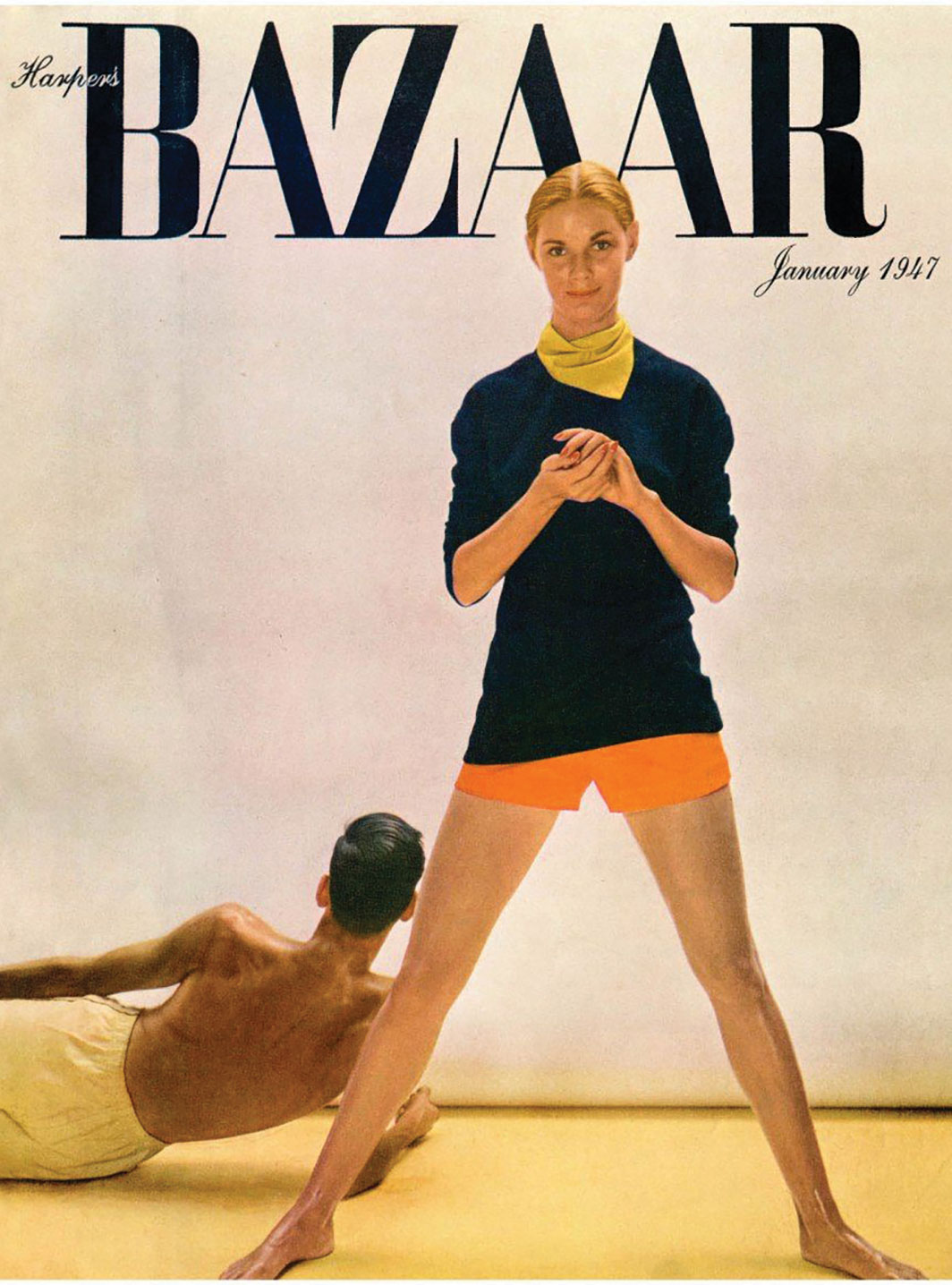

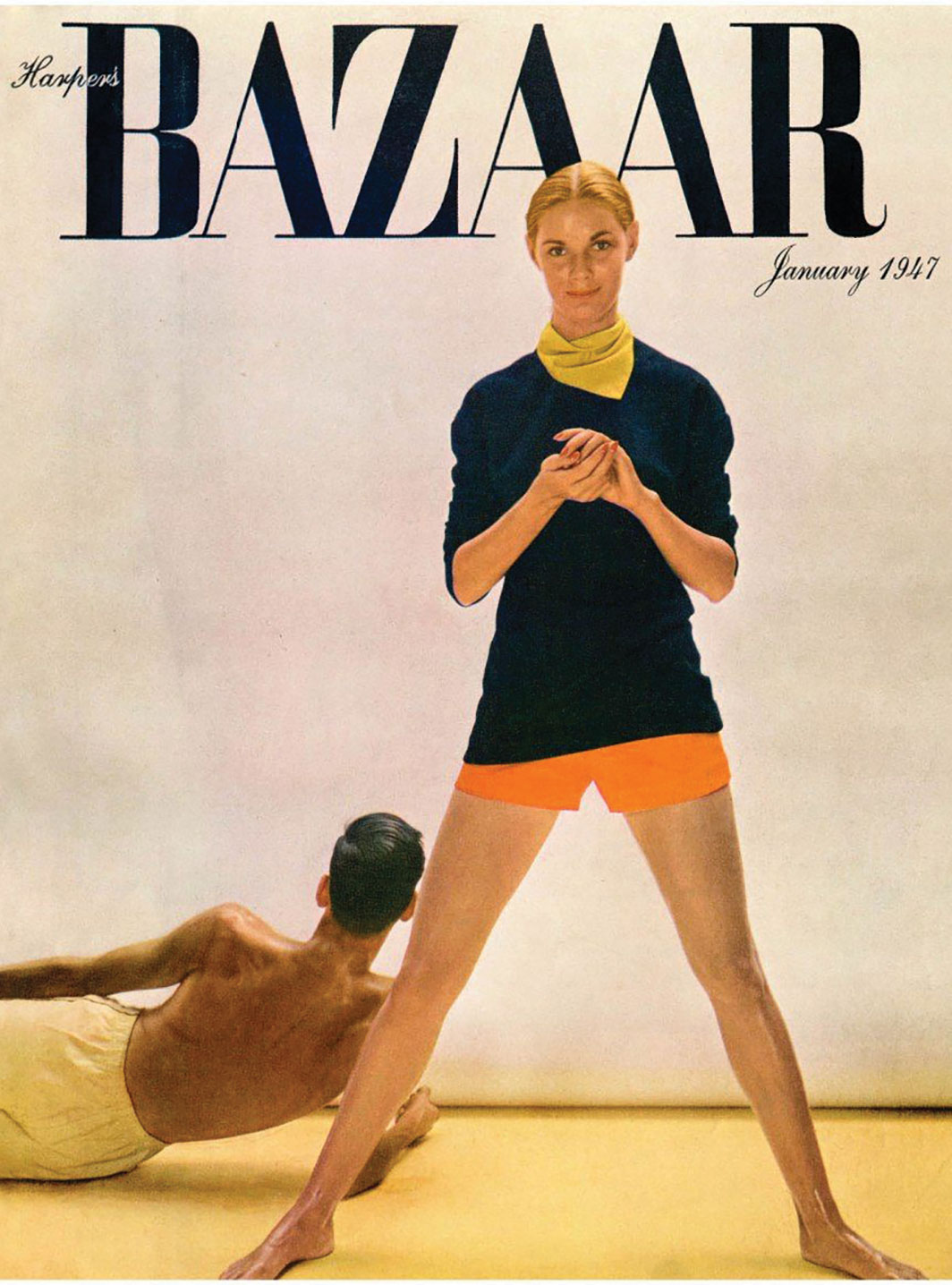

A riddle: What’s made of mink-coated totems, toothpaste Lolitas, Thunderbirds, middlebrow colas, Kotex napkins, and Versace decadence? Answer: Avedon Advertising (Abrams, $125), a three-hundred-and-fifty-page collection of wall-to-wall, in-your-face ads—a dizzying exercise in optic overload. Richard Avedon’s impossibly long-running, far-ranging advertising work—created alongside his fashion and portrait photography—amounted to a sixty-year-long research project. How many forms of mild contradiction could he juggle inside a strictly commercial picture? How many suave anomalies could fit in an ad campaign? How much real desire, humor, or counterintuitive ordinariness could he slip into a world of absolute artifice?

Like Jayne Mansfield in The Girl Can’t Help It, John Waters arrives with ample mystique preceding him. His inflammatory post-Warhol oeuvre now elicits de rigueur hosannas, and it endures precisely because it boldly went beneath—and beyond—anywhere Pop, camp, conceptual art, or Valley of the Dolls had gone before. Waters synthesized gloriously impure conceptual trash: Sins of the Fleshapoids, dreamy Jean Genet, sassy Paul Lynde, the Chelsea Girls, et al. JUMPING INTO THIS VOLUME, an expanded exhibition catalogue covering the give-and-take between the Cologne and New York art scenes in the late 1980s, is like touring sister ghost towns. Beneath the curated relics and cultivated dust bunnies loiters a vibrant, unwholesome, and hazardous synergy, crawling with devil-may-care specters. Have zeitgeist, will travel, this compact but hefty coffee-table book promises: an exchange program from an overcaffeinated period when “yuppie scum” meant a target instead of a target demographic. No Problem showcases artists like Martin Kippenberger, Cindy Sherman, Mike Kelley, Franz West, and Jenny Holzer, who made shrewdly off-balance artworks/japes that could The sun is shining, angry birds are tweeting, bees are dropping like flies: ’Tis a good day for a picnic in the graveyard of honor and humanity. Let us go and pay our disrespects at the tomb of 1959. A bygone age, suffused with the cologne of the quaint. Underneath lies an anarchic spirit waiting to be born again. Or snuffed out once and for all. The spirit in question can be summed up in a saying Graham Greene once procured from Gauguin: “Life being what it is, one dreams of revenge.”

Early in Noah Isenberg’s biography of the legendary filmmaker Edgar G. Ulmer—ultimate auteur of the desperate, no-budget, seventy-minute feature, the proverbial Eisenstein of Poverty Row—the author plucks the phrase “fever swamp” from one of the director’s later efforts, a purple western called The Naked Dawn (1955). The farther Isenberg dives into the blissfully cursed recesses of that swamp, the more Ulmer’s career seems like a perverse figment of a cigar-chomping imp’s imagination. It might have sprung fully deformed from an unproduced Coen brothers script (The Amazing Transparent Director) or lost chapters from Kafka’s Amerika.

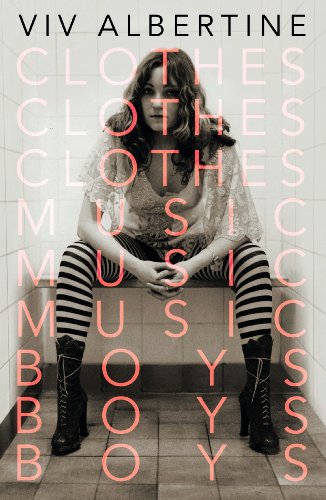

In 1976, Viv Albertine was a twenty-two-year-old Brit punk looking to shock and awe the general populace: “I walk around in little girls’ party dresses, hems slashed and ragged, armholes torn open to make them bigger, the waistline up under my chest. . . . Pippi Longstocking meets Barbarella meets juvenile delinquent. Men look at me and they are confused, they don’t know whether they want to fuck me or kill me. This sartorial ensemble really messes with their heads. Good.”