Isabel Flower

CAMDEN-BORN ARTIST Mickalene Thomas has always used collage and montage to conceptualize her immense painted canvases—glittering portraits and florid interiors encrusted in rhinestones and sequins, each a symphony of pigment and pattern. Muse, her first book of photographs, stars Thomas’s recurrent cast (her mother, lovers, friends, and the artist herself) in a luscious portfolio that is almost classical in its settings and gestures and yet also startlingly unrestrained. Thomas does not digitally alter her photographs. But she does cut them, glue them, and add and subtract found imagery and materials. Portions of the pages in Muse have been strategically removed

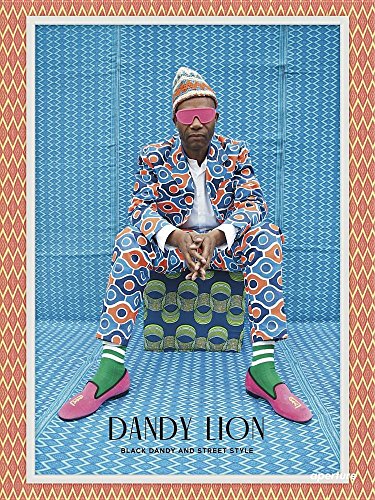

WHILE RIFFLING THROUGH snapshots with her great-uncle Robert a few years ago, the curator Shantrelle P. Lewis realized that she had never once seen him dressed casually. In the introduction to Dandy Lion, she writes that the sartorial resolve of the men in her family inspired the book’s project, which began as an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago in 2015. Lewis defines the black dandy as “a gentleman who intentionally appropriates classical European fashion, but with an African diasporan aesthetic and sensibility.” The book collects old and new photographs of individuals of African descent in West

IT IS NOT UNUSUAL for a photographic project to focus on a single place—a country, a city, a town, a neighborhood—but even so, Khalik Allah’s Souls Against the Concrete is unusually specific. The photographer and filmmaker’s recent book captures people on a single corner, at the intersection of 125th Street and Lexington Avenue in New York City. Growing up, Allah passed this intersection countless times, and his earliest impressions were of “drugs, selling and using, accented by a heavy police presence, bogus arrests, and clouds of smoke.” He began to take photographs there, mostly at night. While to some darkness

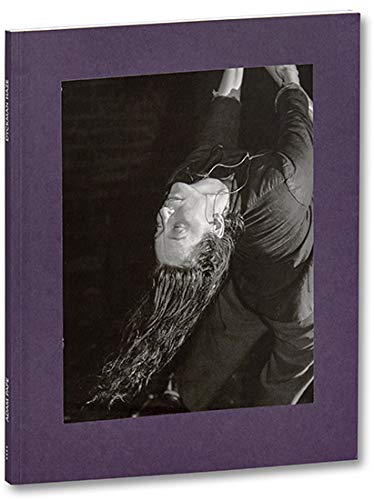

I turned Adam Pape’s new book of black-and-white photographs, Dyckman Haze, over and around several times before I was sure where to begin. Identically sized images of indeterminate orientation appear on both the front and back covers, neither accompanied by a title. One is of a dark cistern; in the other, a person of ambiguous gender folds backward, possibly mid-fall, long hair streaming toward the bottom of the frame. It’s unclear whether this is a moment of fear or of ecstasy.