James Gibbons

Guy Davenport, 2003. The life of the unclassifiable writer, critic, and American philosophe Guy Davenport (1927–2005), spent largely as a university professor in Lexington, Kentucky, seems a cosmopolitan fantasy of how an intellectual might thrive in the provinces. “Living in Kentucky makes every other place delightful,” he once quipped, but Davenport’s isolation gave him the […] Anni Albers, Black-White-Red, 1964 (reproduction of a 1927 original), cotton and silk, 68 x 46″. “Sometimes, the shortest path between two points is serpentine,” writes Christopher Benfey, a professor and author of several studies of nineteenth-century literature and art, in this digressive mix of memoir, art criticism, and historical essay. It comprises autobiographical recollections, a […]

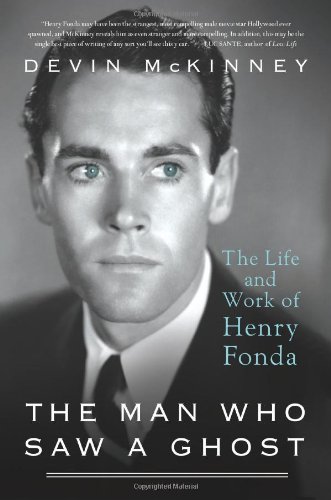

So much of what we know about actor Henry Fonda derives from the authority of his body on-screen: a long, taut, calibrated instrument, most expressive when restrained—as it nearly always was. A lean six feet one, he had the height and physique of a movie aristocrat, but could play a proletarian or a president. Most of all, he always conveyed that, at heart, he was a homegrown American, Nebraska born, in touch with social proprieties but also with the urge to light out for the territory. He perfected an understated style that might be called precisionist, his performances akin to

It’s best to read Joseph McElroy’s Night Soul slowly, warily even, because you’re never far from an unexpected swerve, a surprising shift of gears, or a disclosure of inconspicuous import. Not all these sly, oblique, yet affecting stories are set in the city, but the mode is always urban to the core—a crowding together of impressions and perceptions not necessarily in harmony, and just as likely to deepen ambiguity as to clarify. Take this portrait of an aggressive stranger on the subway who accosts a fellow New Yorker in “Silk, or the Woman with the Bike”: “To hear her speak, Rick Moody’s latest novel is a riotous gloss on an already forgotten flourish of presidential theater: George W. Bush’s 2004 announcement that the United States would send a manned mission to Mars in the coming decades. Bush’s proposal recalled JFK’s optimistic—and fulfilled—moon-landing prediction but was transparently an election-year ploy as the war in Iraq soured; it betrayed an edginess about a new, non-American century of Chinese ascent and epochal domestic decline. Slyly taking Bush at his word, Moody imagines a 2025 NASA expedition to the Red Planet and conjures a not-so-distant future that is less a forecast of the world When Harry Tichborne, at the outset of Laird Hunt’s elegant novel Ray of the Star, crosses the Atlantic for an extended stay in an unnamed city, his journey seems an appropriate migration. In his pairing of somber themes and fanciful ambience, Hunt shares little with his American contemporaries and displays a Continental sensibility that recalls the fabulism of Cees Nooteboom (The Following Story) and the antic charms of Éric Chevillard (On the Ceiling). Written as a series of single-sentence chapters, Hunt’s wave-upon-wave piling of clauses also brings to mind the style of José Saramago. Like these writers, Hunt works in