Kate Sutton

Nicole Miller, Michael in Black, 2018, patinated bronze, 42 x 15 1/2 x 22″. Courtesy the artist and Kristina Kite Gallery, Los Angeles NICOLE MILLER’S Michael in Black is a monograph-as-moodboard, dedicated to the artist’s eponymous bronze sculpture of Michael Jackson kneeling, which was produced from a mold live-cast for a scene in the 1988 video […]

IN THE UNRULY ANNALS of twentieth-century American art, Andrew Wyeth (1917–2009) carved a quiet place for himself as a chronicler of clapboard fronts and windswept fields in the shadeless stretches of Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and, later, Maine. The artist imbued his portraits and landscapes with a kind of sacred plainness, his drybrush paintings capturing the specific dust-in-the-water melancholia of Middle America.

THE STORY OF THE STETTHEIMER SISTERS is prestige TV waiting to happen—Jo March meets Hannah Horvath, set against the splendor of money, modernism, and early-twentieth-century Manhattan (with a summer estate or two thrown in for good measure). The eldest, blonde Carrie, was a consummate hostess who, in her spare time, meticulously crafted an opulent dollhouse. Ettie, the youngest, was a brooding Barnard grad with a temper and a unibrow, who, under her pseudonym “Henrie Waste,” once published a book titled Philosophy: An Autobiographical Fragment. And then there’s Florine, the hazy beauty in the middle, who styled herself as an acute observer,

WHILE THE BALKANS are generally not known for neighborliness, that reputation is still quite recent. Most would date it to the mid-nineteenth century, when the rise of the nation-state suddenly spurred competition over inheritances that had traditionally been shared. The term “Balkanization”—which crystallized the peninsula’s characterization as bitterly divided—was coined by the New York Times only in 1918, in the wake of the Balkan wars, when the ousting of the Ottomans sparked a land grab among the kingdoms of the former Balkan League. If anything, the previous centuries of occupying empires—from Illyrians and Thracians to Byzantines and Bulgarians—had imparted a

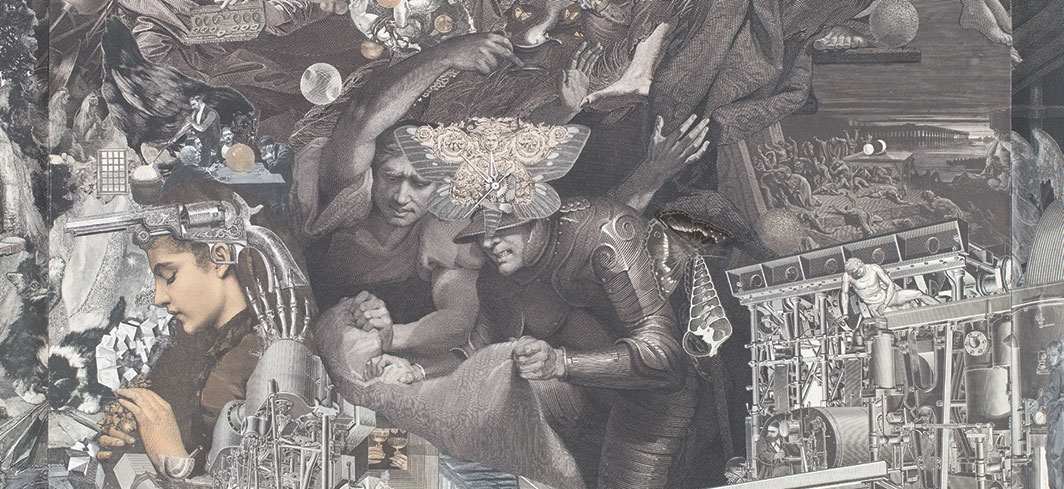

Few artists have proved as agile in mining American visual culture as Jess. Born Burgess Franklin Collins in Long Beach, California, in 1923, the former chemist reconfigured media clippings, mail-order catalogues, and comic strips into complex, beguiling little universes, omnivorous and imaginative, displaying a formidable literacy of both written word and image. His paste-ups (as he preferred to term them) suggested amalgams of almanacs, the backs of cereal boxes, and pages from Life magazine, by way of Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project, James Joyce, the chronicles of Oz, and the stoop-front scrapbooks of the artist’s great-aunt Ivy.

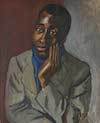

WHEN ALICE NEEL PAINTED a portrait of Harold Cruse in 1950, seventeen years before he published The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, she depicted him thoughtfully grazing his cheek with his fingers, his eyes meeting the painter’s gaze with weathered endurance. Part practicality, part protection, this proximity of hand to face—the standby pose of the untested model—recurs frequently in the paintings collected in Alice Neel, Uptown, the catalogue for a recent survey, curated by Hilton Als, culling paintings from the five decades the artist spent in Spanish Harlem and on the Upper West Side. While Neel’s portraits radiate an undeniable

IN THE CLASSIC American game show Concentration, contestants vied to clear matching tiles from a board, revealing a larger rebus puzzle they had to decipher in order to secure a win. A new monograph on Katherine Bernhardt serves up a similar play of pictograms. Her pattern paintings offer exuberant blooms of iconography, with titles that conduct a rebus-like arithmetic: Couscous + Cigarettes + Toilet Paper + TVs or Key Boards + Soccer Balls + Avocado + Capri Sun + Headphones. And yet there are no riddles to be solved: The artist’s raucous compositions read more like butt-dialed emojigrams. While this

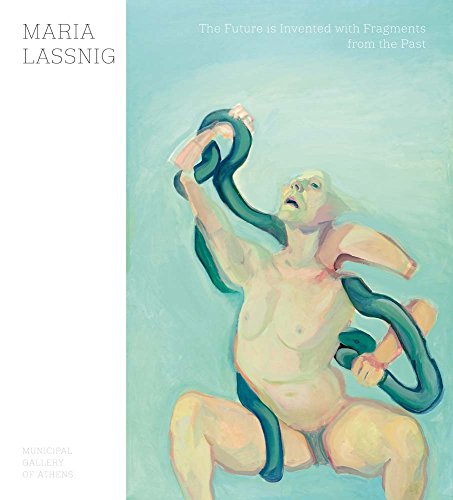

LAST SPRING, DOCUMENTA, the beleaguered quinquennial art exhibition, proposed a rethink of the notion of Europe, decamping to Greece for an attempt at “Learning from Athens,” as its title claimed. Amid the festivities was a show at the Municipal Gallery of Athens, more modest in scale but every bit as ambitious in scope: “Maria Lassnig: The Future Is Invented with Fragments from the Past.” One of the final projects the great Austrian painter developed before her death in 2014, the exhibition compiles sketches, watercolors, and paintings charting Lassnig’s infatuation with Greek mythology. Primarily self-portraits, the images capture the artist infiltrating

IN “STAGES OF LAUGHTER,” Art in America’s 2015 roundup of artists’ insights into humor, painter Amy Sillman recounts studying improv comedy as a means to get a firmer analytical grip on the role of spontaneity in her work. “I’ve always painted without a plan,” she admits. “It’s not that I don’t know what I’m doing, or that I don’t stop and make decisions. I just work by the seat of my pants.”

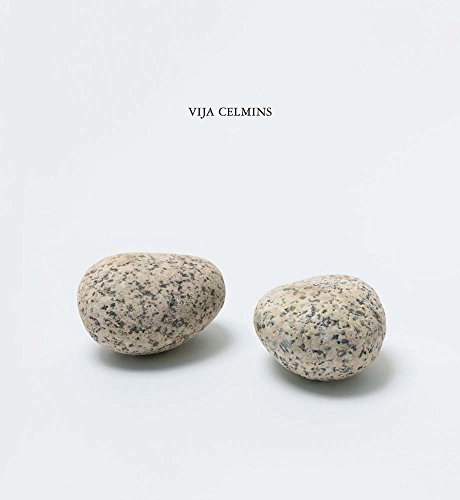

The cover of the catalogue for Vija Celmins’s recent exhibitions at Matthew Marks Gallery in New York and Los Angeles offers a smooth eggshell surface, empty save for two speckled stones and the artist’s name in a modest typeface. With no markers to measure against, these rocks could be pebbles or boulders, though something about their shape suggests they might slip perfectly into one’s palm. Titled simply Two Stones, 1977/2014–16, the objects are nearly identical, except that one is real and the other meticulously modeled in oil and bronze. As Bob Nickas explains in the catalogue’s sole essay, Two Stones