Lauren O’Neill-Butler

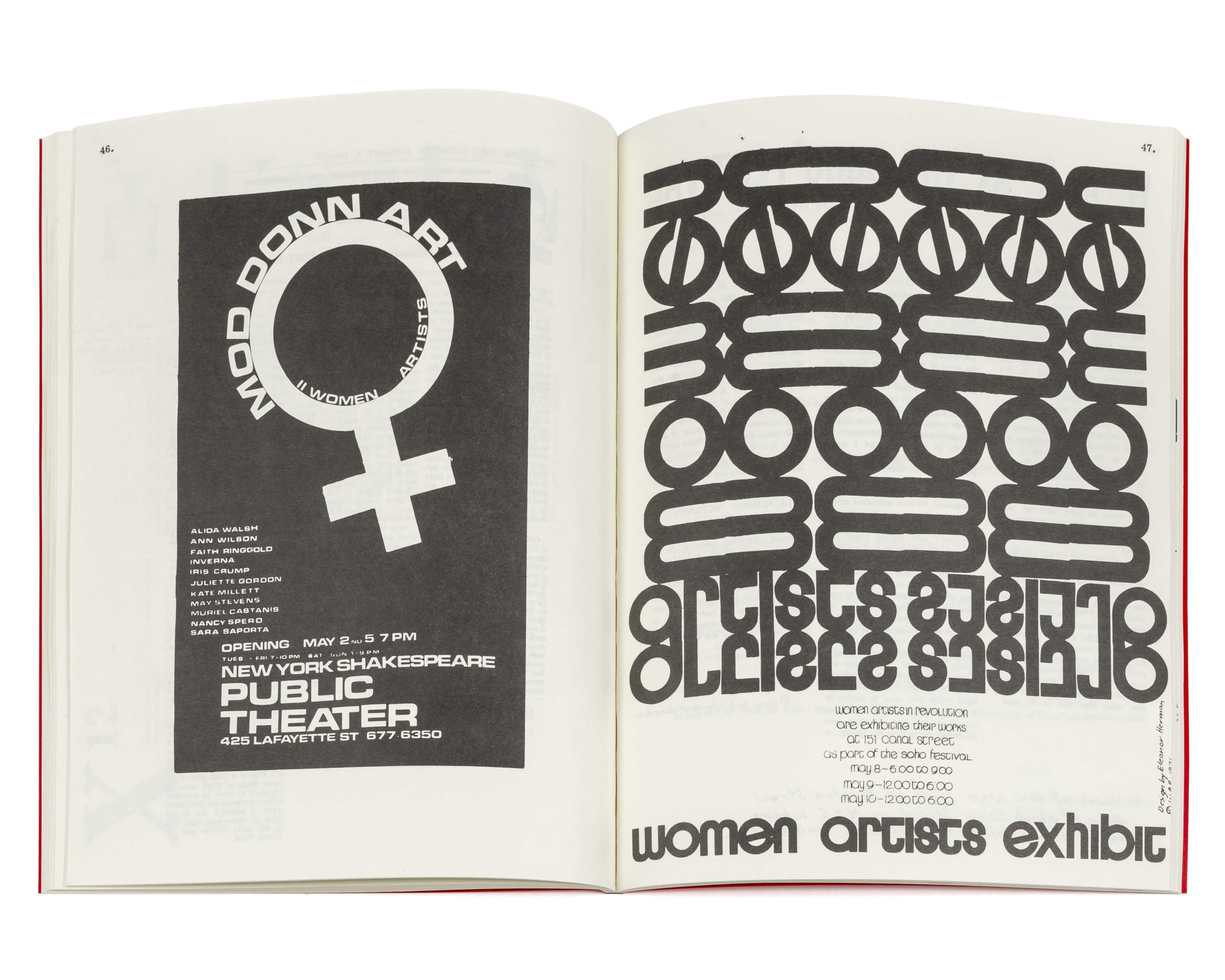

A sense of necessity, a foundation, and a strong community: these are just a few of the keys to effective activism. Though the New York–based collective Women Artists in Revolution (WAR) was short-lived, they burned bright for three years, and emerged in 1969 with these three elements in place. The group of artists, filmmakers, writers, critics, and cultural workers—which didn’t care if its acronym was militaristic, even while the United States pushed its imperialistic agenda in Vietnam—grew out of the Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC). There was an “unstated need among women,” as WAR member Juliette Gordon once wrote, to create

RARE IS THE ART CRITIC who writes novels, though I’ve never really understood why. In 2012, I asked eminent art essayist Lucy R. Lippard about her only published work of creative writing, I See / You Mean (1979). She sighed and said, “I thought I was going to be a great novelist. . . . I was not a great novelist.” Not so rare are fiction writers and poets who pen art criticism. Lippard’s contemporary Susan Sontag famously thought of herself as a great novelist first. In the 1980s, Lynne Tillman began to mix genres in her “Madame Realism” fiction-essays. MOYRA DAVEY, best known as a photographer, is also a writer. Since the early ’90s, the self-described homebody has taken the precariousness of the everyday, often outmoded objects in her life—dusty records, books, hi-fi gear—as a primary subject of her art. In this volume, she extends that inquiry, examining just how elastic the category of “autobiography” can be. Pairing excerpts from writings by (and about) Jean Genet with her own thoughts on keeping a journal, Davey also integrates several recent color prints, all of which document her belongings, travel, and diurnal activities. As in her earlier essays, such as “Index AS LYGIA CLARK’S current MoMA retrospective finally brings her career more fully into view, so, too, arrive overdue scholarship, insights, and revelations about her work. Devotees of the Brazilian artist already know that previous monographs were scant and expensive, and that much of the key criticism about her, as well as her own prose, hadn’t been translated from Portuguese. Offering a strong—if cumbersome—corrective, this catalogue strives to be definitive, with essays by ten authors alongside nearly three hundred spaciously arranged images of Clark’s boundary-breaking art. It begins with a vast overview by the show’s co-curator, Cornelia Butler, moving from Clark’s Lorna Simpson, Leaning Tower, 2011, collage and ink on paper, 11 x 8 1/2″. LORNA SIMPSON’S move away from video and large-scale photographs to drawings and collages might have struck some as a radical shift. Yet her serial portraits of women offer up a ripe extension of her career-long consideration of how identity is endlessly […] Sanja Iveković, Make Up—Make Down, 1978, stills from a color video, 5 minutes 14 seconds. WHEN A RETROSPECTIVE as significant as Croatian artist Sanja Iveković’s “Sweet Violence” doesn’t travel at all, a comprehensive catalogue becomes all the more important. Fortunately, this eponymous summary of the show—which New York’s MoMA featured this past winter—delivers the crucial […]

All the ancient-Greek tragedians put their personal stamps on preexisting myths, but in terms of panache, no one could match Euripides. Even while working within the boundaries of ancient-Greek mythos, he turned tales on their heads, irreverently vamping standards like Elektra. As poet and essayist Anne Carson wagers, “Euripides was a playwright of the fifth century BC who reinvented Greek tragedy, setting it on a path that leads straight to reality TV. His plays broke all the rules, upended convention and outraged conservative critics.”

The lawyer and philosopher Linda Hirshman is a second-wave, no-BS feminist who thinks like a law professor and writes with journalistic chops. She’s also known for writing as if white women’s middle-class experience were universal. It was little wonder that Hirshman dedicated her 2006 manifesto, Get to Work, to a similarly contentious figure, Betty Friedan. In that book, Hirshman laid out a five-point “strategic plan” for “all women to find and be able to pay for the kinds of satisfying lives that a grown up should want to lead.” In short, she rails against being a stay-at-home mom (as she