Lidija Haas

There is by now a vibrant and contentious literature on the relationship between political change and mental illness. Does despair breed compliance, or can you fight back harder the less you have to lose? Could a shared cause of psychological suffering become a cause, rallying and even sustaining the sufferers? Must a mind unhinge itself […]

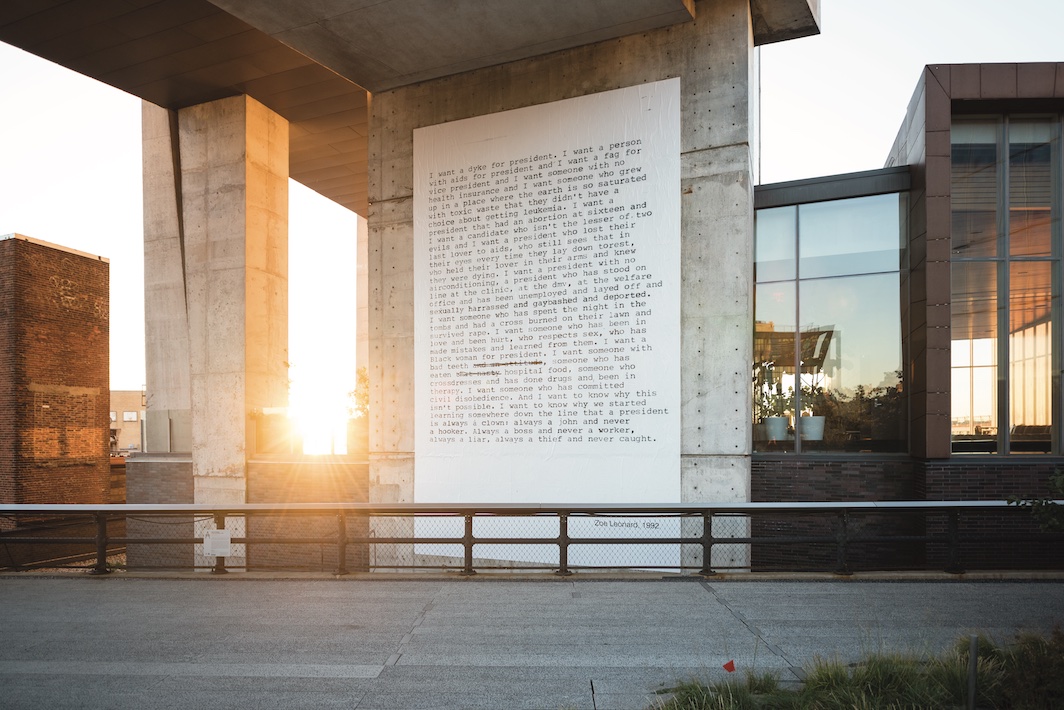

MANIFESTO IS THE FORM THAT EATS AND REPEATS ITSELF. Always layered and paradoxical, it comes disguised as nakedness, directness, aggression. An artwork aspiring to be a speech act—like a threat, a promise, a joke, a spell, a dare. You can’t help but thrill to language that imagines it can get something done. You also can’t help noticing the similar demands and condemnations that ring out across the decades and the centuries—something will be swept away or conjured into being, and it must happen right this moment. While appearing to invent itself ex nihilo, the manifesto grabs whatever magpie trinkets it

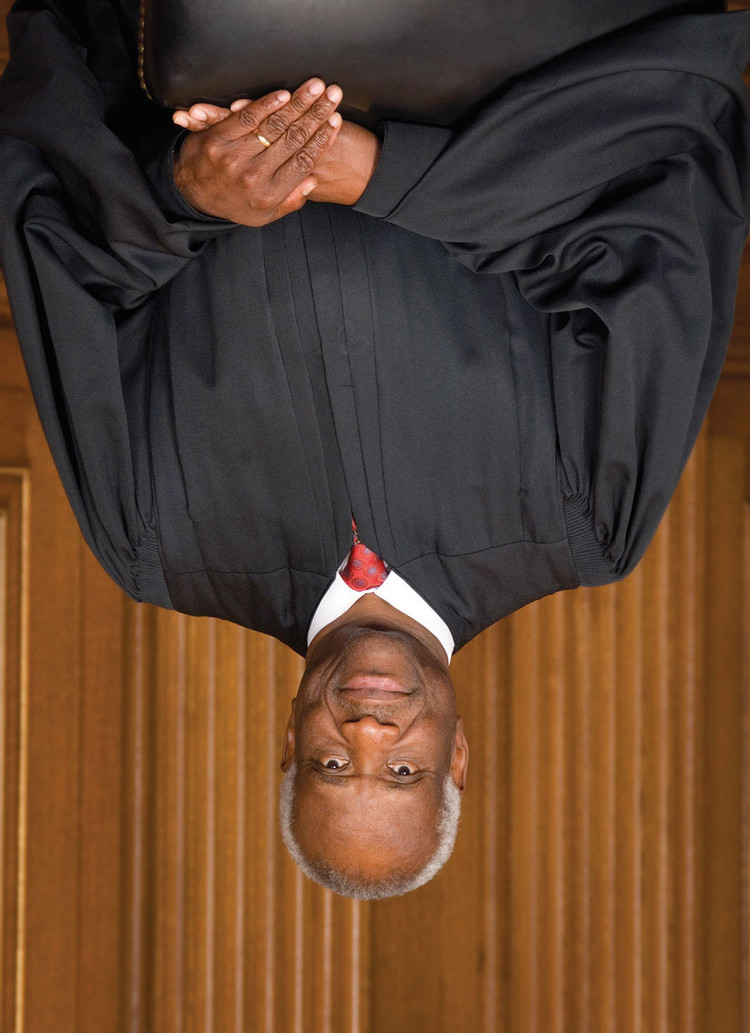

TAKE A MINUTE NOW to write down the first associations that come to your mind regarding Clarence Thomas. You might note that he represents the extreme right wing of the Supreme Court and that, beginning his twenty-ninth term this fall, he is its longest-serving justice, not to mention Donald Trump’s personal favorite. No doubt you’ll think of his alleged sexual harassment of Anita Hill during his tenure at the Department of Education and when he was head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission under Ronald Reagan, of the ordeal she went through when forced to testify about it during his

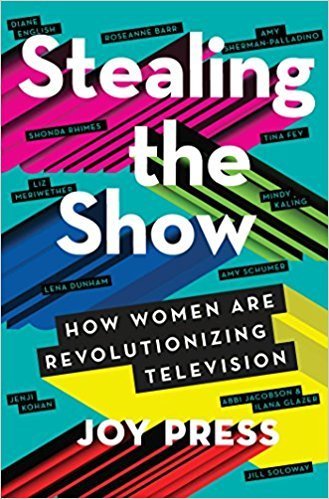

One side effect of the Trump presidency so far—among the mildest and yet, for book reviewers, still very noticeable—has been its distortion of a popular nonfiction genre that wasn’t hurting anyone. Since late 2016, a whole slew of sunny, triumphalist works about the social, political, and cultural progress being made in one corner or another have been forced to add awkward, doomy turns to their introductions and conclusions, the beginnings and ends of their chapters. Thus Joy Press’s Stealing the Show: How Women Are Revolutionizing Television, whose prevailing mood matches its effervescent title, must now frame its reported profiles of

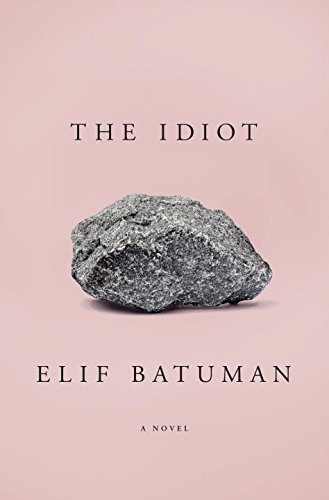

Among those who consider themselves serious readers, it’s seen as infra dig to treat literature as self-help. Fiction is not there to teach us how to live or to help us imagine different ways out of our mundane personal difficulties. Nabokov is stern on this in his Lectures on Literature: “Only children can be excused for identifying themselves with the characters in a book.” Any of us who nonetheless persist in, say, taking a novel as a model for our love lives, might hesitate to start with the nineteenth-century Russian canon, unless we aspire to be connoisseurs of suffering. Not When I was seventeen, I had my long hair cut off in an attempt to emulate Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl. Alas, it turned out that the Cleopatran effect—a look the young Streisand seemingly cultivated through a combination of thick makeup and pure willpower—wasn’t so easy to re-create. I took the precaution of not telling anyone why I’d done it, but even if somebody had wanted to make a joke, Streisand had already beaten them to it. A woman goes to her hairdresser and asks for the “Barbra” look, she used to say. So he takes the hairbrush and breaks

You are heading into the future on a voyage of sexual discovery, and here is what it’s like. Drinking beers with a man you’ve just met online, you think of five or ten other men you already know and would prefer to drink with, were it not for the grim necessity of finding a boyfriend. At Burning Man, you accompany a relatively attractive guy into the so-called orgy dome, but find only other heterosexuals having sex in neat pairs. At a shoot for a website called Public Disgrace, you join an enthusiastic crowd to watch a cheerful twenty-three-year-old being bound, Advice is so much more enjoyable to give than it is to receive that its long flourishing as a genre—from the conduct books and periodicals of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to the current plethora of columns, livechats, and podcasts—could seem mysterious. Of course, watching other people being told what to do might be the most fun of all, which surely helps account for the enduring appeal of the advice column, and explains why living online seems only to enhance that appeal. Yet the genre is also unusual in the opportunities it offers a writer, in its combination of surprise

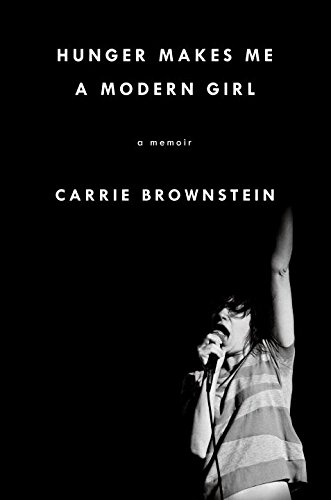

From the opening pages of Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl, it’s clear that Carrie Brownstein, best known as a guitarist and singer in the seminal band Sleater-Kinney, and now as an actor and the cowriter and star of Portlandia, is a writer first. Covering her childhood in the Seattle suburbs, her time in the 1990s Olympia, Washington music scene, and her years recording and touring with Sleater-Kinney, the book sets itself apart from the general run of music memoirs: Well turned, subtle, and clear-eyed, it’s a striking literary accomplishment. I was curious above all about what she read and

“I’ve written a number of essays the past few years,” Dodie Bellamy writes in her new book, When the Sick Rule the World, “and I keep vowing to quit.” We know her essay-quitting hasn’t been going well, not only because we’re reading about it in a Dodie Bellamy essay, but also because these words, which originally appeared in the 2008 chapbook Barf Manifesto, are now nestled in a new collection alongside thirteen other essays, most of which have been written in the years since.