Michelle Orange

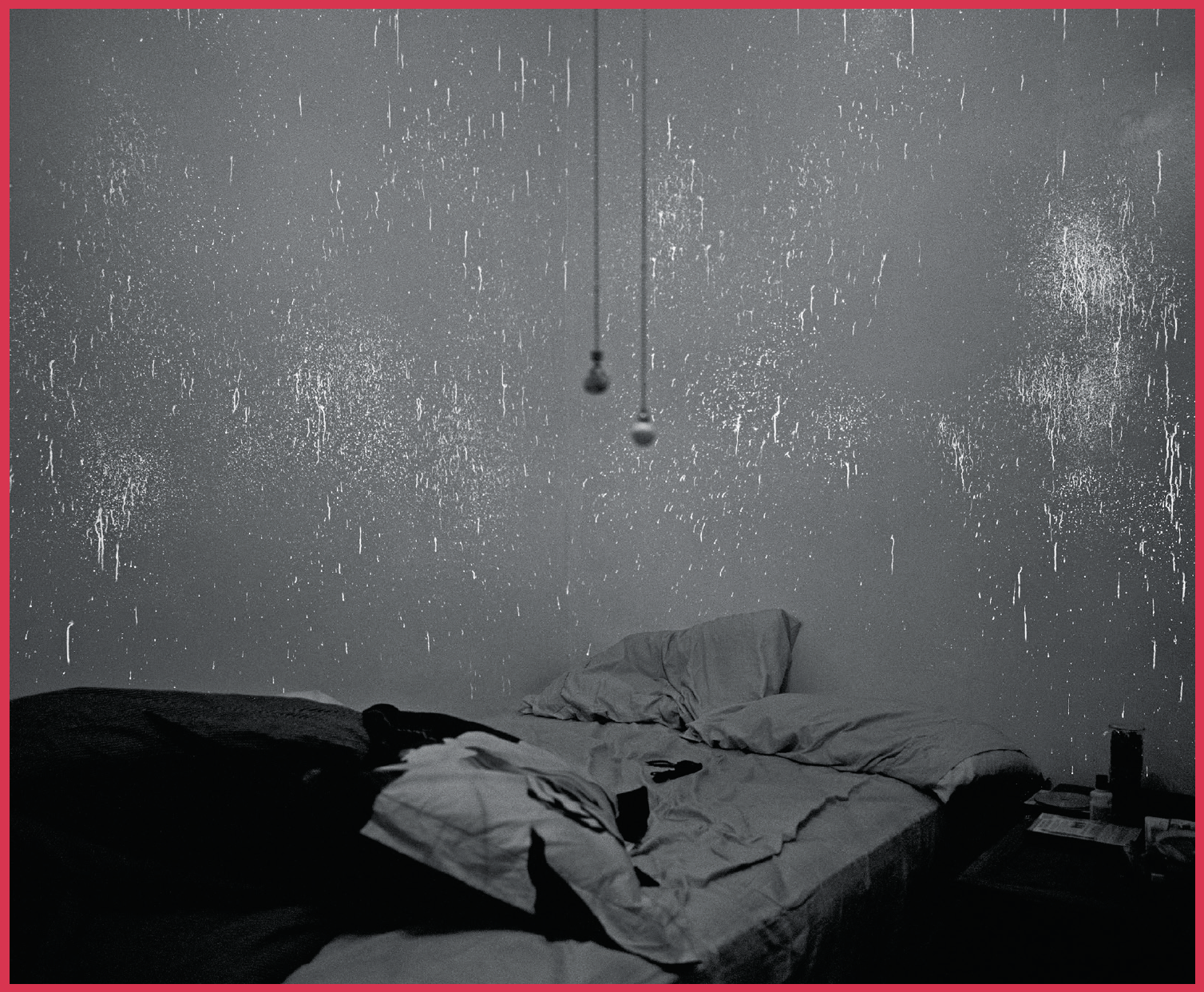

In her 2017 memoir After the Eclipse, Sarah Perry describes preparing for the trial of the man who raped and murdered her mother, Crystal, while twelve-year-old Sarah was asleep—and then not asleep—in the next room. It was twelve years before a DNA match prompted a suspect’s arrest and prosecution. Faced with the prospect of justice but also of reliving her unfathomable trauma, Perry started to run. She wanted her body sleek and strong; she wanted to show the killer her mother’s face, alive, unbroken. She logged regular hours at a gym where a row of treadmills faced a bank of

The last three of Marilynne Robinson’s four novels—the Pulitzer-winning Gilead, Home, and now Lila—apply a canonical sheen to a small Iowa town, a world of dying fathers, prodigal and miracle sons, fallen women, and homemade chicken and dumplings. In each book the same events—often the same conversations—are witnessed and recalled from various, luminously drawn perspectives, layering into a kind of applied sanctity the course of more or less ordinary life.

Bad enough that a new Norman Rush book appears but once a decade; to be a big tease about it seems cruel. As far back as 2005, Rush was describing his new novel, Subtle Bodies, as a “screwball tragedy,” a book concerned with “friendship, male friendship in particular.” The tease was on, and over the next seven years assumed tantric proportions: It would be Rush’s first book set in the United States and not Africa, and much shorter than his previous novels—the five-hundred-page Mating (1991), and the seven-hundred-page Mortals (2003)—with the action taking place on the eve of the 2003

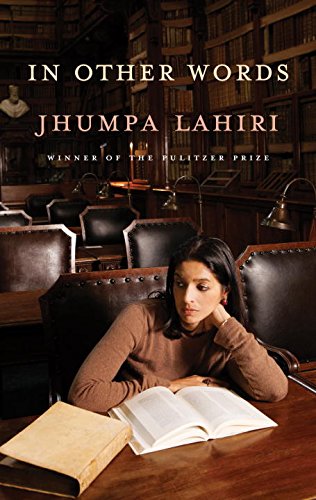

Per publishing custom, the first pages of In Other Words, Jhumpa Lahiri’s fifth book and first essay collection, present a selection of critical praise for her previous work. The nature of this praise, all of it pertaining to Lahiri’s 2013 novel The Lowland, is both predictable and particular, with an emphasis on the author’s reputation as “an elegant stylist.” The blurbs celebrate Lahiri’s “legendarily smooth . . . prose style,” her “brilliant language,” and her ability to place “the perfect words in the perfect order.” Beyond the usual hosannas, what emerges is the sense of an author defined by her