Sam Huber

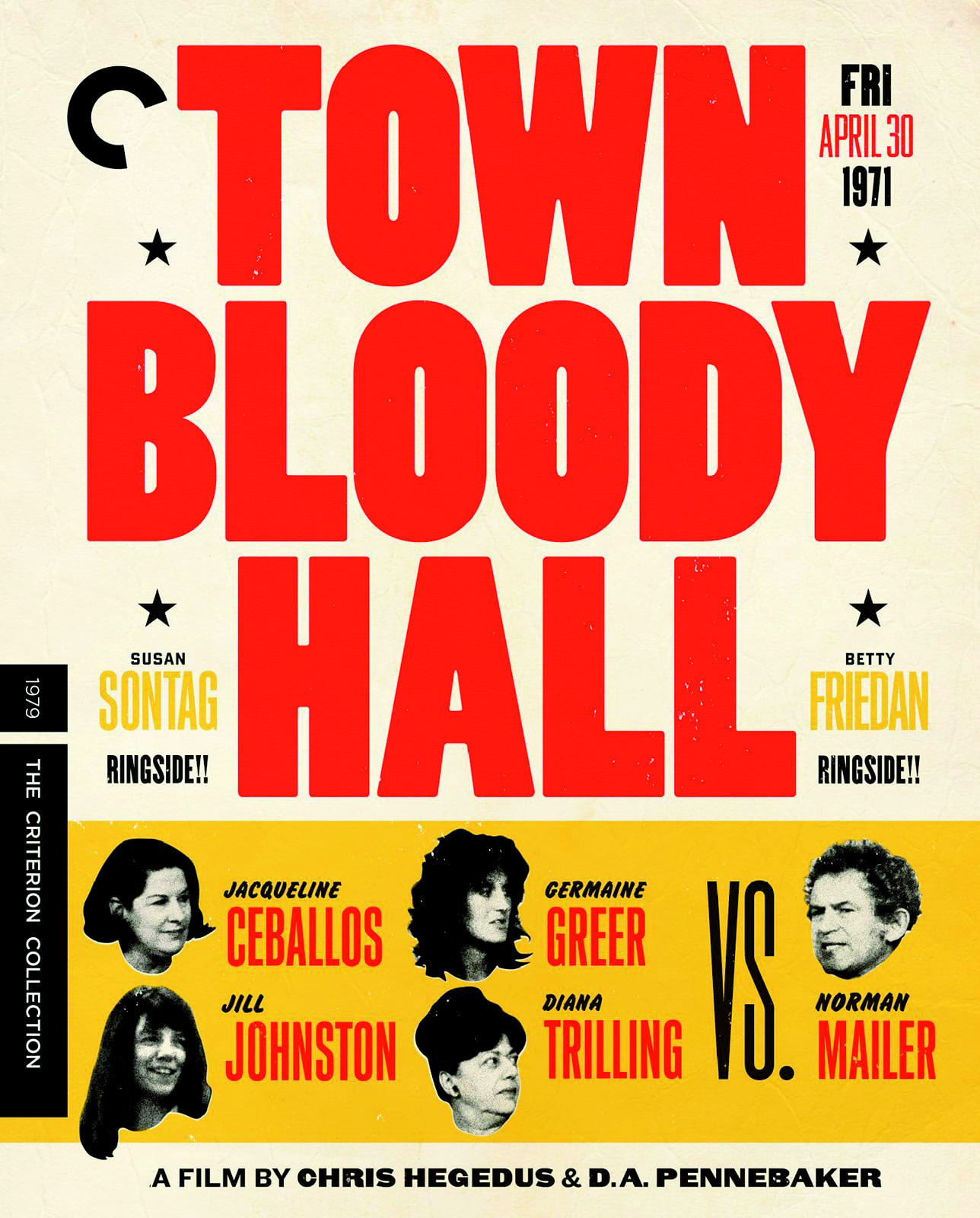

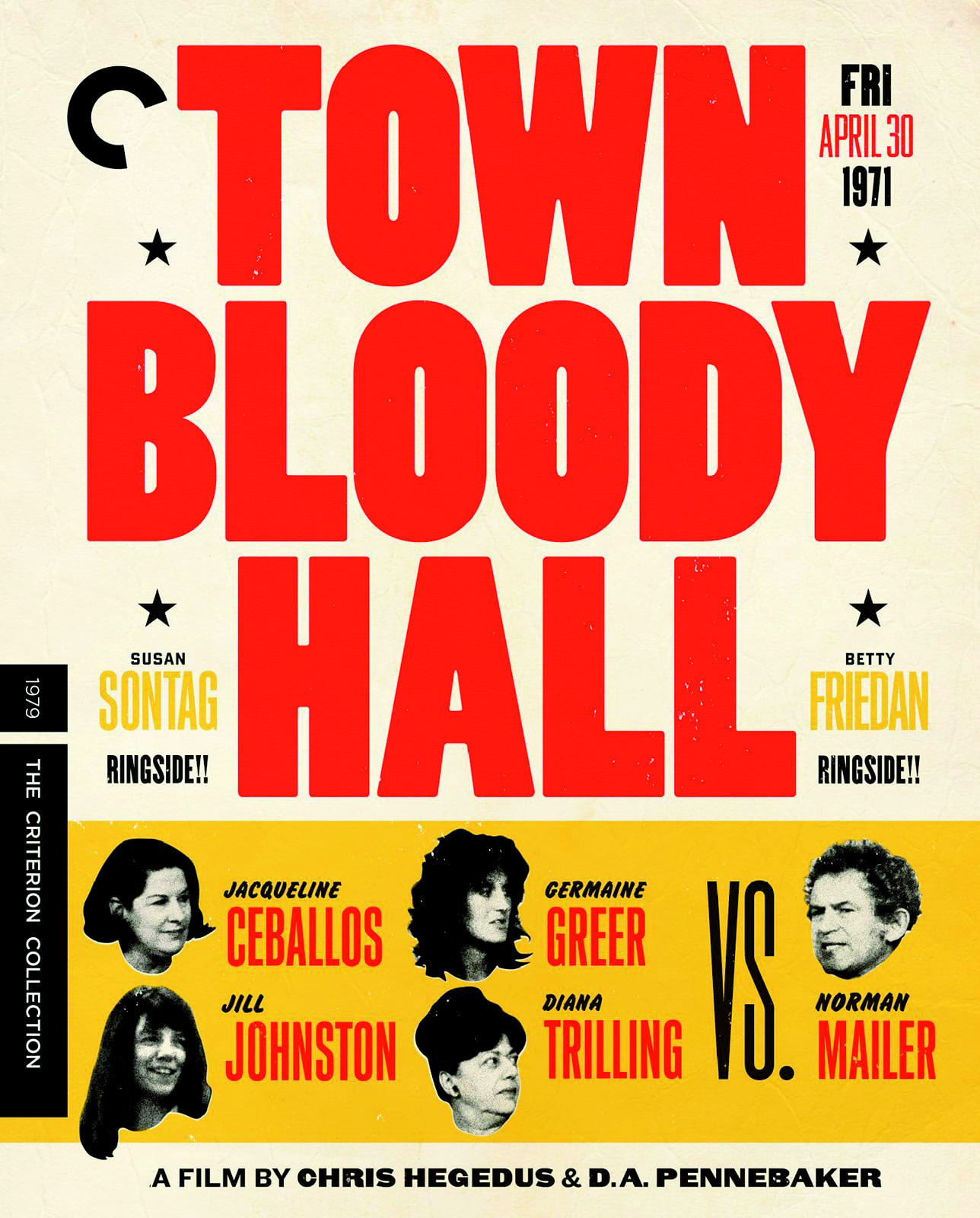

LIKE MANY PEOPLE, I FIRST SAW JILL JOHNSTON in Chris Hegedus and D. A. Pennebaker’s indelible film Town Bloody Hall (1979),which documents a raucous 1971 “dialogue on women’s liberation.” Norman Mailer, the panel’s token misogynist and nominal moderator, introduces Johnston as “that master of free-associational prose in The Village Voice,” for which (I’d later learn) […]

For many of its participants, the women’s liberation movement represented a saving break with an unremittingly bleak past. A switch flipped at the end of the 1960s, and the culture flooded with light. Where once there had been only darkness—Ladies’ Home Journal, back-alley abortions, MRS degrees—now there was feminism: Kate Millett made the cover of Time, Shirley Chisholm made the ballot, and young women picketed bridal fairs and beauty pageants that they might have attended a year before. In 1971, fiction writer Tillie Olsen remarked with awe that “this movement in three years has accumulated a vast new mass of

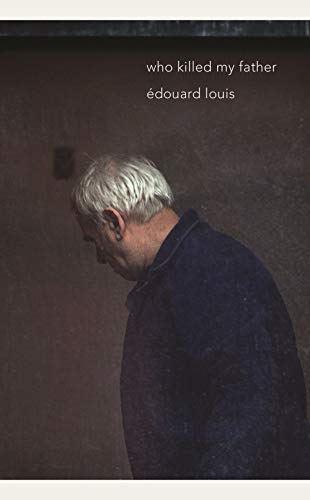

The most striking scene in Who Killed My Father is also its most emblematic. The French novelist Édouard Louis revisits the memory six times in his brief new memoir-cum-polemic, sifting it obsessively as if for hidden information that the scene won’t yield. One evening in 2001, a preadolescent Édouard stages a performance for his parents and a large group of dinner guests. It’s standard proto-queer kid stuff: a now-dated pop song, fussy choreography, backup dancers conscripted from among the guests’ children, and the ringleader self-cast as front woman. The adults watch politely—all except Édouard’s father, who turns away. His withdrawal