Sheila Heti

SHEILA HETI: Your new novel, Help Wanted (W. W. Norton, $29), is about the collective action of a group of workers at a big-box store. They try to get their hated boss out of their hair in a way that is counterintuitive and comic. It feels completely different from your 2013 book, The Love Affairs […]

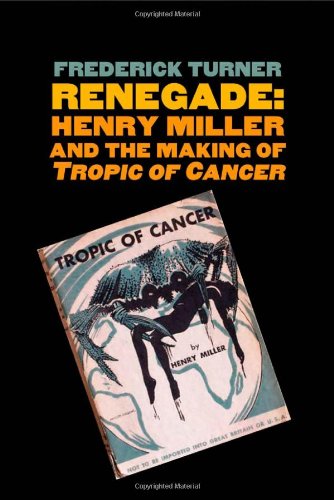

In a letter to his lover, Anaïs Nin, Henry Miller wrote that he was possibly the only writer in our time who has had the chance to write only as he pleased. This kind of hyperbole marked his audacious, pornographic monologue of a first novel, Tropic of Cancer, which was published in the US fifty years ago (after the Supreme Court overturned a quarter-century ban). Now, in Renegade, scholar Frederick Turner reassesses the work, making the case that the book and its author are as quintessentially American as Walt Whitman and Mark Twain. Turner’s volume is part of Yale University Misha Glouberman and Sheila Heti, photo by Lee Towndrow. Misha and I have been good friends for ten years. At the beginning of our friendship, we ran a barroom lecture series together called Trampoline Hall. Now, we are publishing a book called The Chairs Are Where the People Go. Initially I wanted to write a novel called The Moral Development of Misha, but after writing sixty pages, I threw it out. I had hoped to capture Misha’s way of being in the world and his opinions and point of view, but it wasn’t working as fiction. I realized that When we talk about books, we hardly every talk about how they help. It is unfashionable: Browsing the self-help section of a bookstore seems as shameful as picking up a porn magazine at 7-Eleven. Interviewers seldom ask authors, “How is your book meant to help people?” (Instead, they ask the impossible, “What does it mean?”) Yet authors write with the hope of helping readers and themselves—by untangling emotional, intellectual, and existential problems. Perhaps contemporary literary culture doesn’t talk about books’ utility as a way to justify their lofty status as precious, impractical objects. But we can have the best of There are certain books that all young artists read. For example, the other night I met a young woman at a bar. She said she was a cartoonist, so I asked to see her studio. Going over the next night, I noticed on her shelves a book I cherished when I was eighteen: Salvador Dalí’s Diary of a Genius. It was interesting that she had glommed onto Dalí—just as I once had. But what lessons was it teaching her about the artist’s life? Likely the ones I, too, had absorbed, studying certain books so thoroughly that now it gives me