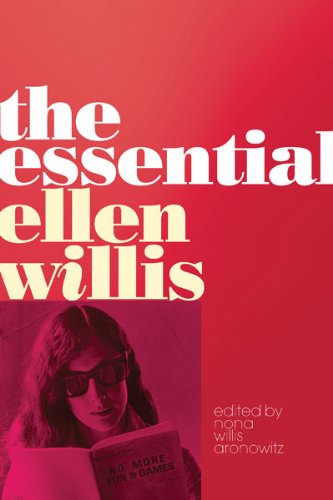

Ellen Willis, whose music writing recently received a much-deserved revival, was often drawn to the counterculture, progressive politics, and how the two overlapped. In this essay, originally published in 1989 in the Village Voice and reprinted in the new book The Essential Ellen Willis, she dwells on feminism, the concept of excess (sex and drugs), abstinence, gay rights, parenthood, and AIDS. Willis often finds her stride in complexity, and here she intricately examines and interrogates the notions of freedom she holds dear. Do all liberation movements set you free? Do conservative ways of life always result in constraint? It’s a moving example of a wonderful mind at work.

“That Blake line,” said my friend—for the purposes of this article I’ll call her Faith, a semi-ironic name, since she is a devout ex-Catholic—“It’s always quoted as ‘ The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.’”

“That’s not right?” I said.

“It’s ‘The roads of excess sometimes lead to the palace of wisdom.’ Very different!”

I looked it up. There it was in “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell,” the “Proverbs from Hell” section, directly following “Drive your cart and your plow over the bones of the dead”: “The road of excess leads to . . . ,” etc. No matter, I realize the poet is playing devil’s advocate; anyway I’m willing to concede that Faith is more of an expert on the subject than I (or, possibly, Blake). Not that I haven’t had my moments, but Faith’s are somehow more—metaphoric. I think, for instance, of the time that, drunk and in the middle of her period, she engaged in a highly baroque night of passion and woke up in the morning to find herself, the man, and the bed covered with gore, a bloody handprint on her wall.

Two years ago Faith joined Alcoholics Anonymous. When she told me, I was doubly surprised. First, because I had never thought of my friend as having “a drinking problem”—a condition I associated with nasty personality traits and inability to function in daily life, certainly not with the all-night pleasure-and-truth-seeking marathons that had seemed to define Faith’s drinking style. The other surprise was that AA was evidently not the simpleminded, Salvation Army–type outfit I had imagined; somewhere along the line it had become the latest outlet for the thwarted utopian energies of the ’60s counterculture. Faith’s AA group, which included cocaine and heroin junkies as well as alcoholics, functioned (or so I inferred) as a kind of beloved community. Within that community one’s alcohol or drug problem was a metaphor for human imperfection, isolation, confusion, despair. True sobriety—not to be confused with compulsive abstinence or puritanical moralism, which were merely the flip side of indulgence—was freedom, transcendence. The point was not self-denial but struggle: confronting the anxiety and pain indulgence had deadened. AA, in short, was a spiritual discipline that, in its post-’60s incarnation, had much in common with that most secular of spiritual disciplines, psychotherapy.

Among the welter of feelings I had about Faith’s new project was envy: I was frustrated by the lack of community in my own life. Having first begun living with a man and then decided to have a baby, I had plunged into the pit of urban middle-class Nuclear Familydom and its seemingly inexorable logic—an oppressively expensive apartment, an editing job (more lucrative than writing, less psychically demanding), a daily life overwhelmed with domestic detail (“moving sand,” the therapist I was complaining to, a fan of Woman in the Dunes, called it), a Sisyphean struggle to keep a love affair from dissolving into a mom-and-pop sandmovers’ combine, and a disquieting erosion of other human relationships. Those of my friends who did not have young children lived in another country, of which I was an expatriate, while other NFs of my acquaintance seemed either content to stay on their own islands or, like us, too exhausted from sandmoving to have much time for bridge-building.

My life as a mother did have a dimension of transcendence, marked by intense passion and sensual delight; yet while I’d always insisted that real passion was inherently subversive, my love for my daughter bound me more and more tightly to the social order. Her father and I had remained unmarried, as a tribute to our belief in free love, in the old-fashioned literal sense, and our rejection of a patriarchal contract. But the structural constraints of parenthood married us more surely than a contract would have done. If there was spiritual discipline involved, it had nothing to do with changing diapers or getting up at night—that was just putting one foot in front of the other, doing what one had to do—but rather with the attempt to maintain an ironic (“Zenlike,” as I thought of it) detachment from our situation, to think of Nuclear Familydom as an educational experience, an ordeal, like Outward Bound.

It didn’t help that I was going through all this during the worst orgy of cultural sentimentality about babies and family since the ’50s. On the other hand, it seemed unlikely that the flowering of my own procreative urge—along with that of so many of my ’60s-generation/feminist peers—had been a simple matter of beating the clock. The pursuit of ecstasy—in freedom of the imagination and a sense of communal possibility as much as in sex, drugs, or rock and roll was no longer our inalienable right. Babies, however, were a socially acceptable source of joy.

At a time when anti-drug hysteria was competing with pro-family mania for the status of chief ’80s obsession, the same logic could be applied to sobriety. So another of my reactions to Faith’s detoxifying was uneasiness. Abstinence might not be the point, but it was the means (unless one somehow achieved the satori of genuinely being able to take a drink or drug or leave it alone). As a metaphor it was troublesome. And it was catching on: Faith pointed out with no little glee that the new aura of AA had lent cleaning up an unprecedented glamour. (As a rule it’s still true that whatever my generation decides to do, whether it’s cleaning up or having babies, becomes a cultural phenomenon. Ecstasy by association, as it were. Neoconservatives hate us more for this than for anything else.) I was less pleased than she to read Elizabeth Taylor’s announcement that she had joined the ranks of the sober. Liz Taylor, whom I’d always cherished as one of the few famous women to barrel down the road of excess with a vengeance—eating, drinking, swearing, fucking, marrying, acquiring diamonds as big as the Ritz. . . . Faith had little sympathy or my discomfort, noting that Liz had scarcely been a happy boozer these last years, burying her- self in all that weight: now she was, judging from the press accounts and especially the pictures, in better shape physically and emotionally than she’d been in a long time.

If I find sobriety as a pop ideal threatening, it’s not for the obvious reason. I’ve never been a drinker, and except for a brief period when I took a lot of psychedelics and smoked marijuana more or less regularly, my forays into drugs have been sporadic and experimental—for the past decade or so virtually non- existent. The point of drugs, for me, was always the eternal moment when you felt like Jesus’s son (and gender be damned); when you found your center, which is another word for sanity or, I assume, sobriety as Faith understands it. But I never found a drug that would guarantee me that moment, or even a more vulgar euphoria: acid, grass, speed, coke, even Quaaludes (I’ve never tried heroin), all were unpredictable, potentially treacherous, as likely to concentrate anxiety as to blow it away. Context was all-important—set and setting, as they called it in those days. My emotional state, amplified or undercut by the collective emotional atmosphere, made the difference between a good trip, a bad trip, or no trip at all.

For me, the ability to get high (I don’t mean only on drugs) flourished in the atmosphere of abandon that defined the ’60s—that pervasive cultural invitation to leap boundaries, challenge limits, try anything, want everything, overload the senses, let go. Unlike the iconic figures of the era and their many anonymous disciples, I never embraced excess as a fundamental principle of being, an imperative to keep gathering speed until exhaustion or disaster ensued. (My experience of the ’60s did have its—“dark side” is a bit too melodramatic; “rough edges” is closer. But more about that later.) Rather, since my own characteristic defense against the terror of living was not counterphobic indulgence but good old inhibition and control, the valorization of too much allowed me, for the first time in my life, to have something like enough.

Transcendence through discipline—as in meditation, or macrobiotics, or voluntary poverty, or living off the land—was always the antithesis in the ’60s dialectic: in context it added another flavor to a rich stew of choices and made for some interesting, to say the least, syntheses. But its contemporary variants are the only game in town, emblems of scarcity. Another metaphor: runners by the thousand, urging on their bodies until the endorphins kick in. The runners’ high, an extra reward for the work-well-done of tuning up one’s cardiovascular system. What’s scarce in the current scheme of things is not (for the shrinking middle class, anyway) rewards but grace, the unearned, the serendipitous. The space to lie down or wander off the map.

Of course, there’s a moral question in all this: the Elizabeth Taylor question, or, to put it more starkly, the Janis Joplin question. If ever anyone needed some concept of sobriety as transcendence —not to mention a beloved community offering the acceptance and empathy of fellow imperfect human beings for whom her celebrity was beside the point—it was Janis. The embrace of excess strangled her: would I drive my cart and my plow over her bones? I think of Bob Dylan, avatar of excess cum puritanical moralist, laying into the antiheroine of “Like a Rolling Stone” for letting other people get her kicks for her. And I think of Faith again, of an incident that, unlike the Night of the Red Hand, doesn’t make an amusing or colorful story: expansive on wine, wanting to be open to the unearned and serendipitous, she let a pretty boy she met in a club come home with her. Inside her door the pretty boy turned into a rapist, crazy, menacing; lust gave way to violence.

But I don’t want to oversimplify in the other direction. It was not the ’60s, after all, that caused Janis Joplin’s misery; what we know about her years as odd- girl-out in Port Arthur, Texas, makes that plain. The ’60s did allow her to break out of Port Arthur, to find, for a painfully short but no less real time, her voice, her beauty, her powers—her version of redemption. Had rock and roll, Haight-Ashbury, the whole thing never happened, I can’t imagine that her life would have been better; it might not even have been longer. Nor does Faith regret her time on the road. Among ’60s veterans in AA there is the shared recognition of a paradox, one that separates the “new sobriety” from its fundamentalist heritage: taking drugs enriched their vision, was in fact a powerful catalyst for the very experience of transcendence, and yearning for it, that now defines their abstinence. It’s crucial not to forget that the limits we challenged—of mechanistic rationalism, patriarchal authority, high culture, a morality deeply suspicious of pleasure, a “realism” defined as resignation—were prisons. Still are.

The image of excess that bedevils the conservative mind even more than reefer madness is that of the orgy—anonymous, indiscriminate, unrestrained, guiltless sex. As contemporary mythology has it (and as the right continually repeats with fear and gloating) the sexual revolution of the ’60s was an exercise in “promiscuity”; because of AIDS, promiscuity is now fatal; therefore the sexual revolution was a disastrous mistake. This syllogism, which takes the now-devastated gay sex-bar-and-bathhouse world as the paradigm for ’60s sexual culture, says less about the actual habits of that culture than about the envious prurience of this one. But then, myths generally have more to do with imaginative reality than with the practical sort, and if the idea of AIDS as retribution (God’s or nature’s) wields power far beyond the constituencies of Pat Robertson and Norman Podhoretz, if the white, non-needle-using heterosexual population’s fears of contagion have far outstripped the present danger, it’s in part because the traditionalist’s sexual nightmares are the underside of the counterculture’s dreams. There was the dream of recovering innocence, dumping our Oedipal baggage, getting back to the polymorphous perversity of childhood and starting over; the dream of a beneficent sexual energy flowing freely, without defenses, suspicion, guilt, shame; the dream of transcending possessiveness and jealousy; the dream, at its most apocalyptic, of universal love: it was one thing to have sex with strangers, quite another if the strangers were your brothers and sisters, if you need not fear games, or contempt, or violence.

Few people tried seriously to live this vision, even in circles where LSD and hippie rhetoric flowed as freely as libido was supposed to; the New York writers and artists I hung out with were positively snarky about it all. Yet the dreams put their stamp on us.

Context, again, was crucial, and in these skittish days it bears repeating that the context of sexual utopianism was, in the first place, the near-universal revolt of young people against what are now nostalgically referred to as “traditional values”: that is, women’s chastity policed by the dubious promise of male “respect” and lifetime monogamy; by the withholding of birth control and the criminalizing of abortion; by the threat of social ostracism, sexual violence and exploitation, forced marriage and motherhood. Men’s schizophrenia, expressed in hypocritical “respect” for the frustrating good girl and irrational contempt for the willing bad one, pride in their lust as the emblem of their maleness and disgust with it as the evidence of their “animal natures.” Homosexuality unspeakable and invisible. By the end of the ’50s the sexual revolution had begun, but the first version to gain ascendancy was a conservative one—it defined sex as a commodity, or a form of healthy exercise, that merely needed to be made more available. Furious at the moral code we’d grown up with—I knew no one of either sex who didn’t feel in some way crushed by it—yet uninspired by the curiously antierotic liberalism proposed as an alternative, we were ripe for ways of imagining sex that might begin to heal our wounds.

Imagination was the key (as John Lennon was to claim, in a song too often misjudged as simpleminded). My own sexual behavior remained relatively conventional; during most of the years when the ’60s sexual imagination was at its height, I was living with lovers for the most part monogamously. While I rejected monogamy as a moral obligation, it was mostly the sense of freedom I wanted, the right (after the years of not enough) to feel open to the world’s possibilities, without prior censorship. I disliked the idea of the on-principle Exclusive Couple; it was smug, claustrophobic. On acid trips I perceived that there was indeed another kind of sexual love, better than romantic love as we knew it, more profoundly accepting and trusting, free of the insecurity that demands ownership. I even left one man for another in pursuit, or so I thought, of that version of the dream. Of course, to be capable of translating such transient flashes of perception into my real, daily life, I (and he) would have had to be born again, into a different world, and my new relationship was soon as mired in coupledom as the other one had been.

Still . . . a couple of years later, this same man and I were sharing a two-family house with a married couple and their baby. I decided, for once, to act on my fantasies of extending sexual intimacy beyond the sacred dyad, and my initiative was enthusiastically received by all concerned. From the conventional point of view I got my comeuppance. It turned out that while the husband and I were pursuing an enjoyable experiment, expanding our friendship, transcending the nuclear family, and so on, our mates were doing something rather different—were infatuated with each other, in fact. It hurt, it was disruptive, it made me for a time feel like killing two people. Yet I could never honestly say I was sorry I’d started the whole thing. The power of that urge to stretch the limits could not cancel out jealousy and possessiveness, but it could compete. And, in a sense, win.

Though a respect for history compels me to add that my friend, the family man who also wanted more, later divorced his wife, remarried, and became a born-again Christian.

History and its convolutions. . . . The affirmation of love’s body against the life-denying brutality of “traditional values” was at the heart of what made me a feminist. As a popular Emma Goldman T-shirt implied, if I couldn’t fuck it wasn’t my revolution. For me, for thousands of women, the explosion of radical feminism was a supremely sexy moment; we had the courage of our desires as we’d never had before. It was not only that we could make new demands of our male lovers or seek out female ones; not only that we were rejecting the sexual shame and self-hatred endemic to our condition. We were making history, defining our fate, for once taking center stage and telling men how it was going to be. Sisterhood was powerful therefore erotic.

And yet it was feminism—not the new right, certainly not the as yet-unknown AIDS virus—that first displaced the counterculture’s vision of sex with a considerably harsher view. I don’t mean only, or even primarily, the brand of feminism that has attacked sex as a form of male power, the sex drive as an ideological construct, and “sexual liberation” as a euphemism for rape. In the early radical feminist movement such polemics were regarded as eccentric (though I was not the only one who, with overt relish and unconscious condescension, admired them as rhetorical excess, a Dadaist provocation, part of the exhilarating racket of newly discovered voices transgressing the first law of femaleness: be nice). Most of us felt about the sexual revolution what Gandhi reputedly thought of Western civilization—that it would be a good idea. There was, however, the little matter of abortion rights; there was the continuing legal and social tolerance of rape; there were all those “brothers” who spoke of ecstasy but fucked with their egos, looked down on women who were “too” free, and thought the most damning name they could call a feminist was “lesbian.” And then—our new sense of ourselves might be aphrodisiac, but the rage that went along with it wasn’t. Nor were men’s reactions—ridicule, fake solicitude, guilt, defensiveness, hysteria, and, when none of that shut us up, what-do-you-bitches-want fury—much of a turn-on for either sex.

It was the best, the worst, the most enlightening, the most bewildering of times. Feminism intensified my utopian sexual imagination, made me desperate to get what I really wanted, not “after the revolution” but now—even as it intensified my skepticism, chilling me with awareness of how deeply relations between the sexes were corrupted and, ultimately, calling into question the very nature of my images of desire. For my sexual fantasies were permeated with the iconography of masculine-feminine, seduction-surrender, were above all centered on the union of male and female genitals as the transcendent aim of sex (not, surely not, one form of joining among others). Why did I want “what I really wanted,” and did I really want it? And—oh, shit, forget about utopia— what were the chances of steering some sort of livable path between schizophrenia (or amnesia) and kill-joy self-consciousness in bed?

But there was one more convolution to come: feminism inspired gay liberation and with it a renewed vision of untrammeled sex as the key to freedom, power, and community. Ironically (at least from my point of view), it was a vision of sex among men. The lesbian movement of the ’70s was not primarily about liberating desire (though there were, of course, plenty of individual and subcultural exceptions) but about extending female solidarity; for the gay male community solidarity was, at its core, about desire. To this version of the sexual revolution I was, of course, doubly an outsider. That aspect of the gay male imagination that most repelled and fascinated the straight world, the culture of anonymous, ritualistic sex and sensation for pure sensation’s sake, repelled and fascinated me. It seemed the epitome of distance and difference—except when an evocative piece of fiction or theater, or more rarely a conversation about sex with a gay man, would awake in me some ghost of a forgotten fantasy, reminding me that otherness is at bottom a defensive illusion.

AIDS, paradoxically, has impressed this on me in a deeper and more lasting way. That’s partly because the issues AIDS raises transcend sex, per se. The eruption of a massive plague-like epidemic, of a sort we were supposed to have “conquered” long ago, not only threatens to test our economic resources and social conscience in unprecedented ways, but attacks the fundamental faith of our scientific-technological culture—that we can dominate nature. And for this very reason, the sexual significance of A IDS transcends the demographics of high-and low-risk groups. On one level the sexual liberation movements embody the revolt of “the natural” against social domination, yet they are unthinkable without technology. Modern contraception, safe childbirth and abortion, antibiotics drastically reduced the risks of sex, and in doing so encouraged the heady fantasy of sex with no risk at all. AIDS is hardly the first challenge to that fantasy: women found out a while ago that the only truly zipless contraceptives, the pill and IUD, were dangerous—sometimes deadly—and in some parts of the world, resistant strains of gonorrhea are already out of control. I suspect that as we learn how to “manage” AIDS —with imperfect but workable vaccines, treatments that keep people alive and functioning, condoms, and other precautions—our sense of it as a dramatic watershed, a radical break with the past, will diminish (even, eventually, for gay men), just as condoms themselves will become an ordinary part of sexual culture instead of an emotionally charged symbol of (take your pick) all hated barriers to delight or rampant permissiveness. Still, our sexual imagination is bound to change. The idea of achieving safe sex through chemistry will come to seem a quaint piece of Americana, akin to the notion of abolishing scarcity through unlimited economic growth.

So does this mean the conservatives are right, the dream is over? A lot of erstwhile dreamers, gay men especially, are feeling a kind of rebellious despair as they contemplate the shadow of death between desire and act. What can sexual freedom possibly mean if not pleasure unconstricted by fear or calculation? Yet—and I speak as a woman who is passionately pro-abortion, who remembers nostalgically the ease and security of the pill—there is something muddled about a logic that equates freedom with safety. Freedom is inherently risky, which is the reason for rules and limits in the first place; the paradox of the ’60s generation is that we felt secure enough, economically and sexually, to reject security. The risks people took were real and so were the losses: the deaths, breakdowns, burnouts, addictions, the paranoia and nihilism, “revolutionary” crimes and totalitarian religious cults, poverty, and prison terms. Though the casualties of drugs and politics have been more conspicuous, sex has never been safe certainly not for women and gay men: in a misogynist, homophobic culture suffused with sexual rage, to be a “whore” or a “pervert” is to “ask for” punishment.

In many post-AIDS elegies to sexual liberation lurks a sentimental idea of gay male culture as paradise lost, a haven of pure pleasure invaded by the serpent of disease. Yet the appeal of the gay fast lane on the road of excess surely had something to do with being outlaws, defying taboos, confronting and ritualizing danger, assimilating it to the marrow of a pleasure that was, in part, a triumph over fear. It could not be a coincidence that the sexual anonymity invested with so much excitement had historically been a survival strategy for gay men in the closet. At the same time, gay men’s pursuit of sex without attachment reflected a widespread male fantasy—one that men who want sex with women must usually conceal or play down. For many men, freedom to separate sex from relationship without guilt or hypocrisy has always been what sexual liberation is about. But the conventionally masculine dream of pure lust is, I’m convinced, as conservative in its way as the conventionally feminine romanticism that converts lust to pure emotion—or, for that matter, as the patriarchal values that subordinate passion to marriage and procreation. All are attempts to tame sex, to make it safe by holding something back. For the objective risks of sex would not terrify us half so much if they did not reinforce a more primal inner threat. To abandon ourselves utterly to sensation and emotion—to give up the boundaries and limits that keep us in control—would be, for most of us, like cutting loose from gravity and watching the earth spin. Dissolution of the ego is the death we fear; the real sexual revolution, the one no virus can keep us from imagining, is the struggle to face that fear, transcend it, and let go.

My favorite statement about risk and excess is also my favorite ’60s joke. It’s a Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers comic strip in which one of the skanky protagonists gets busted for dope. At the police station he is granted his one phone call. The last panel shows him burbling euphorically into the phone, ordering one large with pepperoni, mushrooms, green peppers.

The road of excess is a roller coaster, the palace of wisdom a funhouse. Liberation is playful, useless, unproductive, for itself—too much. Like Little Richard’s screams, Phil Spector’s wall of sound, Dylan’s leopard-skin pillbox hat, Janis’s feather boa, the foxhunt on Sgt. Pepper. Or, to stick with our main metaphor, the custom cars Tom Wolfe immortalized, Ken Kesey’s Pranksters’ Day-Glo bus, the Byrds’ magic carpet, Jefferson Airplane. The trouble is, the trip always ends up heading for somewhere, loaded down with all the tragic baggage of human deprivation and yearning. And when that happens, the vehicles start going off the track, over the edge, down the slippery slope from yes she said yes she said yes to just say no. Which is where irony comes in.

I’m a political person, a political radical. I believe that the struggle for freedom, pleasure, transcendence is not just an individual matter. The social system that organizes our lives, and as far as possible channels our desire, is antagonistic to that struggle; to change this requires collective effort. The moment a movement coalesces can be, should be itself an occasion of freedom, pleasure, and transcendence, but it is never only that. Radical movements by definition focus attention on the gap between present and future, and cast their participants, for the present, in the negative role of opposition. Fighting entrenched power means drawing battle lines, defining the enemy. In the ’60s and after, the strains of radicalism I identify with have defined the enemy as all forms of domination and hierarchy—beginning but not ending with sex, race, and class—and from this point of view, as a French leftist slogan from the May ’68 upheavals put it, “We are all Jews and Germans.” Which doesn’t mean that we’re all equally victims and oppressors, or that the differences don’t matter, just that there are few of us who haven’t abused power in some contexts, suffered powerlessness in others. And that all of us, oppressors and victims alike, have had to make our bargains with the system—bargains often secret even from ourselves—for the sake of survival and, yes, for those moments of freedom, pleasure, and transcendence that give survival meaning.

So to be a radical as I’ve defined it implies self-consciousness and self- criticism, a commitment to (in the language of that segment of the ’60s and ’70s left most heavily influenced by feminist consciousness-raising) confronting not only our own oppression but the ways we oppress others. And since it’s politics we’re talking about, not therapy, this confrontation is of necessity a collective process . . . and already we’re in very deep waters indeed.

In 1970 I was living with a group of people running a movement hangout for antiwar GIs. It was my first venture into the mixed left since becoming a radical feminist, and my sense of embattlement was acute. Predictably, I was angriest at the men I felt closest to, the ones I knew really did care—about me, about having good politics; so often they simply didn’t get it, a solid, dumb lump of resistance masquerading as incomprehension of the simplest, clearest demands for reciprocity. At the same time, another woman in the project, a feminist from a working-class background, was confronting me and the rest of our group of predominantly middle-class lefties about the myriad of crude and subtle ways we were oppressing her and the mostly working-class soldiers we worked with. And I began to see it all from the other side: my good intentions; my struggle to see myself as my friend saw me, to change; my continual falling short; my friend’s anger and hurt when I just didn’t get it; my own dumb lump that, to me, often felt indistinguishable from the core of my identity. Male guilt made me furious (“Don’t sit there feeling guilty, just get your fucking foot off my neck”), but now I was mired in guilt, resentful about having to feel guilty, guilty about being resentful, and so on.

In “Salt of the Earth,” an ostensible ode to the “hard-working people,” Mick Jagger suddenly blurts that they don’t look real to him, they look so strange. On one awful acid trip I saw with excruciating clarity just how deeply and pervasively I experienced poor people as alien, how the very word “poor” embodied that implacable distance called pity. And of course I saw that from the other side too. I don’t remember if this glimpse into hell-as-other-people made me any less angry at men, but it certainly made me more despairing: I didn’t look real to them; the rest was commentary.

More and more it seemed that everything that gave me pleasure, kept me sane, soothed (or distracted from) the wound of female otherness was a function of my privileges—education, leisure, certain kinds of self-esteem, work I enjoyed that let me live like a bohemian, and most crucially the luxury of distance, therefore insulation, from certain kinds of human misery. I might agree, as an intellectual proposition, that only a violent revolution could break the power of the corporate state, but imagining what that meant filled me with revulsion and terror; I was glad there was no practical prospect of it. What my friend really wanted (I knew, because I wanted the same thing from men) was that I give up my blinders and live, no exit, with relentless awareness of her pain, as she had to do: only then would I be truly committed to revolution, whatever it entailed. To my shame I couldn’t do this, couldn’t bring myself to what I saw as a self- immolation at once necessary and intolerable.

Something was wrong, I realized dimly, something was out of whack. Political virtue equated with sacrifice, pleasure with corruption—how had I gotten back there? Yet seeing how class distorted my vision had shaken my faith in my judgment. Part of being oppressed was having one’s perceptions negated; part of being an oppressor was doing the negating. I reminded myself of this when a soldier I didn’t like or trust became my friend’s lover and moved into our house. My friend thought I was cold to him for class reasons—he was uneducated, inarticulate, with a kind of bumpkin style. I accepted her analysis, suppressed my qualms, and tried to welcome the man as housemate and brother. Then it turned out that everything he had told us, even his birthday, was a lie.

I felt ambushed, but I’d done it to myself: pursuing revolutionary purity by handing someone else responsibility for my choices (yet another form of exploitation, she would have said if she’d known). Yes, there was something wrong, something sinister, even: I didn’t have the words for it, didn’t yet have Jonestown and Cambodia as reference points, but I smelled death. This was where excess led when fed by desperation and hubris instead of exuberance and hope. I was depressed for a long time. Many years and shrink sessions later it occurred to me that I was addicted to being right.

In an earlier, more innocent time I am sitting with friends in a coffeeshop in Toronto. We are New York rock critics in town for some festival or press junket. Our hair is very long, our dress ranges from East Village Indian to neo-pop. We have smoked some hash and are giggling with abandon. We order hamburgers and sundaes, then spaghetti, then, as I recall, more ice cream. The waitress smiles at us, inspiring a frisson of mock-paranoia around the table: does she know? Suddenly it strikes me very funny that the dope is illegal and the food is not.

Segue to the present, one of those days when conversation with my daughter, Nona, age four, goes something like this: “I want gum. I want a lollipop. I want ices. I want a cookie. I want another cookie, a different cookie. I want a Coke. I want candy. That candy. I want . . . .”

“You had ices today. No sweets till after dinner. No candy. No more cookies. You’ll rot your teeth. You’ll upset your stomach. You won’t eat real food. NO!”

“I want—”

Once I answered by singing, “ You can’t always get what you want.” That silenced her for a minute. I finished the verse. She looked at me thoughtfully. “But I want candy,” she said.

This is no doubt the kind of exchange detractors of the ’60s have in mind when they dismiss the counterculture as “infantile.” I feel them looking over my shoulder as I play the part of repressive civilization frustrating limitless desire. I think they miss the point.

I love sugar. Controlling my craving for sweets is always a struggle, giving in to it an ambivalent, illicit pleasure. Sugar is my quick fix for anxiety or depression, an effortless and reliable consolation in a demanding, insecure world: the only problem is, a minute later you’re hungry again. Determined to spare Nona this compulsion, I decided on a strategy even before she was born. I got her father to agree that we would treat sweets as casually as any other food, neither forbid them nor limit them nor insist that she finish her “real food” first. If we didn’t give her the idea that sweets were evil/special/scarce, they would hold no fascination for her, and we could trust her to set her own limits. In short, we would put to the empirical test our cultural-radical faith in the self-regulating child.

Our strategy didn’t fail; it never got a fair trial. Neither of us could stick to it. After a while I grasped the obvious: if I were capable of treating sweets as casually as any other food, I wouldn’t have had to make an issue of it in the first place. And the anxious double messages I was transmitting were more likely to encourage an obsession with the stuff than if I’d followed the conventional advice, set limits I was comfortable with, and enforced them.

I do that now, but it’s a matter of damage control. For Nona sweets are the object and the symbol of desire. Often the litany of Iwantcandygumcookies is code for wanting more from us. More time and patience and acceptance. More babying and reassurance. More freedom and power. We try to listen to what she’s really saying, to give her what she wants when it’s also what she needs. But we are parents in an age of scarcity and constraint, in the grip of family life, which is structured to ensure that no one gets enough time, patience, acceptance, babying, and reassurance, or freedom and power. In protest, Nona demands too much; we deny her for her own good; and so it begins again.

From The Essential Ellen Willis, published by the University of Minnesota Press.