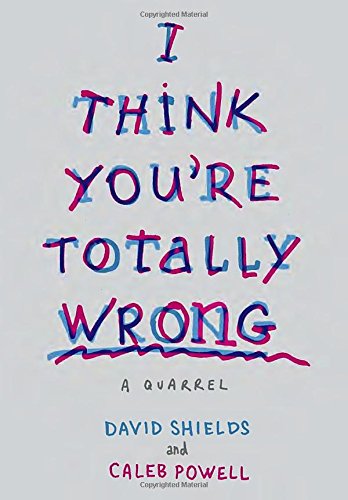

What should we call works in which male artists share a meal while listening to themselves talk? I Think You’re Totally Wrong records pieces of conversation between David Shields and his former student Caleb Powell during a four-day trip on which they discuss how to balance writing and living. “It’s an ancient form: two white guys bullshitting,” Shields says, as the two watch movies, drink beer, and hike the mountains above Seattle. “Why are we even doing this?” he adds. “Why aren’t we home with our wives and children?” Questions like these populate the book, as the leading men try to position such debates as polished art, excerpted from the messiness of real life. The posturing itself seems to be one of the key features of the genre: men (real and fictional) adopting a prompt under which they nakedly try to answer life’s big questions.

The book’s premise comes from lines in the W. B. Yeats poem “The Choice”: “The intellect of man is forced to choose / Perfection of the life, or of the work.” Shields represents the man who chose work over experience. He has published sixteen books, has one child, and has never strayed far from Seattle. Powell, who has never published a book, has three children and traveled the world. (Both, however, write professionally and are married to wives described as having successful, if more conventional, careers.) As the two self-consciously try to join the tradition of men wrestling with their artistic calling, they only circle around the cliché—life or art?—that drives their forebears, and arrive at few new answers to that old question. They’re good, however, at defining the fairly embarrassing genre, and even better at embodying it—sometimes on purpose, but more often inadvertently.

The two men talk for 250 pages, referencing The Trip and Sideways, reaching for Waiting for Godot and the Socratic dialogues. “We’re going to go to a cabin for four days and yell at each other, and out of that we’ll try to produce a My Dinner with Andre-like exchange,” Powell says, evoking the 1981 film that the two men want to replicate in their unscripted, but much less organic, experience. The solipsism can be repellant, as an offhand comment by Powell illustrates. “Why don’t you commit suicide in the next year?” he asks, referencing Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, the book-length interview of David Foster Wallace conducted by then Rolling Stone reporter David Lipsky. Shields responds, “Then we’d have a book for sure.”

I Think You’re Totally Wrong is billed as a conversation between Shields and Powell, but it’s clearly Shields’s project, plotted by his own anxieties and formalistic tics as he uses the words of other sources to stand in for his own. The discussion is reconstructed in chronological fragments, punctuated by old letters and lines from films. Readers of Reality Hunger will recognize here another work of collage, pulling its material from a variety of sources, relevant or not. The transcript is most entertaining when the two are digging into each other’s writing, particularly Shields’s, as teacher and former student incise the other’s insecurities. This is no bromance. “You have a hesitancy to judge,” Powell says to Shields, “a moral relativism that allows anything into play, and it comes across as amoral.” “I don’t know what to say,” Shields remarks toward the end of the book. “You don’t have a clue how to read my work.”

Shields and Powell share unattractive anecdotes about their childhoods as well as their wives; they call up their own white guilt, misogyny, and homophobia without censor. “To me, one way that human beings can become better, or at least that art can serve people, is if the writer or the artist shows how flawed he or she actually is,” Shields proclaims. “Basically the royal road to salvation, for me, lies through an artist saying very uncompromising things about himself.” Wallace is the prime example, “flaying himself alive in order for us to understand ourselves better.”

But in trying so hard to emulate those they envision as their predecessors, they find the limits of an already limited genre. The food and activities that score these conversations seem like apologies for just talking, as if alone that might be too indulgent or too revealing. Is all this activity a crutch for insecurity? When men go off to eat and talk it has to be an adventure; when women do, it’s called a brunch. In giving so many references, Shields and Powell miss the point that this form depends on being referential, narcissistically so. Understanding and defining the genre might help them save their own book, but even that is a selfish act. Unflattering comments are often followed by paragraph breaks, which can feel like pauses meant for eye rolls where self-awareness should be. These obvious moments for self-reflection, where none occurs, punctuate a project that’s supposed to be about admitting flaws—but that kind of failure, too, reveals itself as a hallmark of the form.

The defining characteristic of works like theirs, Shields and Powell decide, is that “at the end the characters switch roles in a way that feels credible,” making a reversal or grand gesture (getting married, having or not having an affair, returning home) that makes clearer the line between life and art. But even more characteristic is the subtle assumption that men experience all that is worth considering; women are important only insofar as they act as constraints or catalysts to men’s art-making. “Andre leaves his wife and family, too,” Shields explains, but then comes back to them. Steve Coogan chooses not to go to America with his girlfriend in order to stay with his children in England; Rob Brydon comes back to his family after considering cheating on his wife. Shields and Powell, too, go back to their respective families; the story ends at Shields’s home, as he insists that Powell come inside instead of rushing back to his own family.

The publication timing seems apt given the controversy over The Interview, a bromance/buddy comedy starring James Franco that is in the same vein of the movies for which he and his collaborators have become known. (Jason Segel, incidentally, stars as Wallace in The End of the Tour, the film version of Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself.) I Think You’re Totally Wrong was adapted into a film directed by Franco, which premiered at Sundance last month to coincide with the book’s release. In the film version, Shields and Powell play themselves and act out the transcript, canonizing their personas from the book while presumably reflecting on them at the same time. It might be the most apt literary crossover Franco could attempt.

Why are there so few debates produced on film or in book form among female artists about these same issues? In Jenny Offill’s novel Dept. of Speculation (2014), the narrator, a writer, is trying to make writing out of what might be the failure of the life she chose. She has a young child; she has recently learned that her husband is having an affair. “My plan was to never get married,” she explains. “I was going to be an art monster instead.” The stakes of the questions about life versus art are inherently higher for women, and Offill presents far more nuanced and successful versions of the questions I Think You’re Totally Wrong asks. Men have been able to debate whether or not to become art monsters for a long time. (The freedom to naval-gaze leads to a great deal of naval-gazing.) In contrast to a parade of egotistic male actors, writers, and comedians, Offill’s narrator doesn’t even give her name. She constellates an answer in her mind, arguing only with herself.

“Maybe she’s like Andre’s wife,” Shields says about the woman Powell is married to, after Powell explains how he went on a six-month trip to Taiwan after proposing to his wife. “Andre doesn’t evoke his wife,” Powell says back. “Sure he does,” Shields insists. “I have a very specific sense of her.” But Powell corrects him: “We know hardly anything about her. Trivia: she’s sitting in the bar as an extra.” I’d like to have heard it from her.

Alexandra Pechman is a writer living in New York.