Perhaps the most famous single line in Guillaume Apollinaire’s body of work is the opening declaration of his 1912 poem “Zone:” “You’re tired of this old world at last.” “Zone” heralds modernity—with its urban setting, its montage of images (the Eiffel Tower, billboards, a “ghetto clock running backwards”), and its jump cuts through time and space. The poem marks a transition between the lyricism of a prior generation of French verse and changing ways of seeing and imagining fostered by the proliferation of new technologies of speed and mechanization. And yet, for all his weariness of the old world, Apollinaire is nowhere near as virulently anti-passéist as his contemporaries the Italian Futurists were. In the breathless rush of Apollinaire’s lines, insouciant lightness and song are never far away.

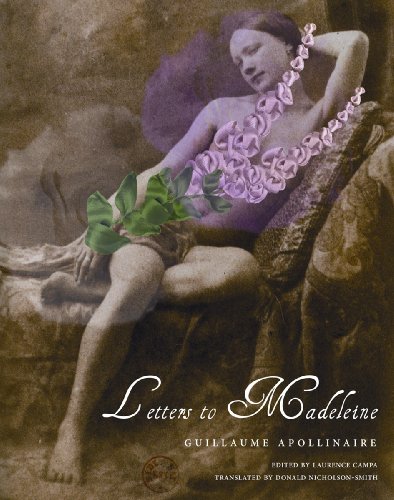

With the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, Apollinaire—an assiduously cosmopolitan promoter of new movements in art, from Cubism to German Expressionism—enlisted in the French army. On New Year’s Day in 1915, while traveling by train from Marseilles to Nice, he met a young schoolteacher from Algeria named Madeleine Pagès, and their encounter soon blossomed into an intense epistolary relationship. Apollinaire’s side of the correspondence has been assembled in Letters to Madeleine, recently translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. These letters—containing the first versions of many of the poems later published in the poet’s last collection, Calligrammes—are indispensable to lovers of modern poetry, and their origins in what the poet called “the very forefront of France-in-arms,” amid the horrors of trench warfare, make them a powerful testimonial of the Great War, on the level of classic accounts by authors such as Robert Graves, Wilfred Owen, Erich Maria Remarque, and Siegfried Sassoon.

Most of all, what unfolds over the roughly eighteen months of Gui (as he signs his name) and Madeleine’s correspondence is a love story of beauty, erotic power, and an ultimately tragic denouement. The book reads with the cumulative intensity and irresistible élan of a great novel. Although Madeleine’s letters are absent here, her voice is nonetheless discernible in the poet’s correspondence: We sense her character in Gui’s attentive writing, his sensitivity to her thoughts and feelings, and in his occasional quotes from her. It is clear that he is the driving force in the relationship, beginning by apostrophizing her as “my little fairy” and, once the two have agreed to an engagement, moving towards ever more amorously charged modes of address (“my panther”) in which erotic elements come to the fore. The prospect of marriage awakens Gui’s conventional side and, in a revealing passage, he compares the “duty” of a soldier with the “duty” of married life: “The ease with which I carry out my tasks [at the front] is offset by the great distress the work causes me . . . Yes my love the idea of duty must enter love freely, so as to subject whatever is unbridled in passion to the order that is the source of strength, grace, and in a word, harmony.” Yet he is also given to calling Madeleine “my little slave” and demanding obedience from her, as he wears down her initial resistance to some of his bolder declarations and inspires her to enter—tentatively—the passionate realm he describes. Clearly, their shared awareness that he could die at any moment contributes to the urgency of his demands and her complaisance. At times, his ardent sentiments and his descriptions of the conditions in which he lives intertwine in a torrential welter of words.

As the squalor of the battlefield worsens, Madeleine becomes an object of what a poetic precursor to Apollinaire—the medieval troubadour Jaufre Rudel—called amor de lonh (love from afar), where passion for the beloved is magnified and ennobled by distance. (Especially poignant in this connection is the fact that Rudel was also separated from his beloved by a pointless war for which he volunteered—in his case the Second Crusade.) Gui writes: “Without having experienced the wretchedness of life here oneself no one could imagine it. Love I adore you, yet how very odd it is that since your two letters arrived everything seems fine to me. It is quite extraordinary how you have transformed this grim life. I may lead my section over the top tonight.”

Having affirmed early on the necessity of chastity while on the battlefield, Gui sublimates his desires into long, almost mystical, present-tense descriptions of imagined sexual acts with his virginal lover. In these erotic letters and the “secret poems” that accompany them, the ancient yet ever-renewed dyad of love and war, of Eros and Thanatos, is beautifully articulated. Madeleine’s body—“the Lily, the Rose” —becomes transformed into a sacred precinct at whose “seven doors” Gui offers up tributes. “I set you oh Madeleine oh my beauty above the world / Like the beacon of all light.” The Surrealist desideratum of “words making love” has no finer exemplar than these secret poem-letters.

Such an overdetermined image of the beloved, particularly when fabricated exclusively by the poet’s imagination (and in conditions of omnipresent death and destruction) is invariably fragile. Gui’s mounting expectations for his long-awaited leave and his first extended encounter with Madeleine—almost a year to the day after their first meeting—were perhaps fated to be dashed, though how or why they were can only be surmised. It could have been the alien-seeming quality of civilian life after long days and nights spent on the front, the bourgeois family milieu in which Madeleine lived, a resurgence of shyness on her part, or perhaps all of the above. In any case, the letters Gui wrote after meeting her again show a decline in intensity: there is affection, but it seems rote. In an eerie recollection of “Zone,” he repeatedly talks of being “tired” (though now his weariness has extended to the “new” world of catastrophe that is the modern era). When he is wounded in the head by shrapnel, gets out of the army, and is sent back to Paris for recuperation, he begs her: “Above all do not come, it would be too emotional for me. Do not write me sad letters either . . . they terrify me.” And shortly thereafter: “I am not the man I used to be.”

According to the fictionalized vida of Rudel, his love afar was the Countess of Tripoli. When he became mortally ill on his return from the Crusades, she visited him, and once he set eyes on her, he died, whereupon she retired to a convent. Whereas Madeleine never married (replicating the Countess’s abjuration of all other love) and kept all of Gui’s letters, Gui chose to leap into the maelstrom of the new rather than linger on the pain of the past. Perhaps by refusing to see Madeleine, he was turning his back on the dreamed “order” of a marriage that had guided him through war’s chaotic agonies. But these letters to Madeleine are a kind of adventure carried out in the face of death, a haven from the charnel house he had entered —in short, a triumphant affirmation of the emancipating disorder that love always brings. In a world still blasted and blighted by war, we can read this volume and think not only of the tragic passion of Gui and Madeleine, but of all the lovers separated by war, and of the young men or women who somewhere, at this moment, are expressing their love in defiance of a world of hostilities.

Nicholson-Smith’s translation has met the formidable challenge of finding an English equivalent to Apollinaire’s prose in all its registers, never descending into anachronism and maintaining a remarkable consistency of voice. As a labor of love, Nicholson-Smith’s work does as much as anything to remind us, as Apollinaire wrote, that “whatever does not belong to love is so much lost.”

Christopher Winks teaches Comparative Literature at Queens College/CUNY.