Edward St. Aubyn wrote his first novel shirtless, drenched in psychological sweat. In Never Mind, the fruit of that strain, we meet a number of characters, but only one or two—side characters—who don’t seem doomed. A father rapes his son. The same father murders a helpless injured person, and his friends don’t disapprove. One imagines a harrowed publicist gamely trying taglines: Why read a novel when you can read a drill? At the same time, St. Aubyn’s prose is so harsh and pretty, so funny and apt, that one reads helplessly on, reaching thickets of trauma less and less bearable.

In the ensuing Patrick Melrose novels, the interplay of the protagonist’s protean, unremitting pain and St. Aubyn’s sculpted, Old World style grows even more dynamic. Sometimes, as in Bad News and Some Hope, the books read like the howl of Henry Rollins as processed by the probing, gently paradoxical mind of Henry James. Sometimes, as in Mother’s Milk and At Last, this irony softens. To replace the pleasures of the friction, St. Aubyn offers direct, psychological insight and aphorism. Patrick says of his ex-girlfriend, Julia, with whom he starts an affair: “She was kind, she was careful, she was accommodating. He was going to have to rely on the machine of their situation to grind them down, as he knew it would.” The acid rigor of these lines adds a new dimension to the novels, a new type of pleasure to read in wait for. That these passages are so quotable rarely detracts from the momentum of the books. Usually, they arrive in icy sweats of urgency. Patrick longs for the words he writes to help his cause. Since the birth of his children, he is no longer able to bear drifting analytically through life. For their sake, to avoid passing on the hell of his inner life, he wants answers.

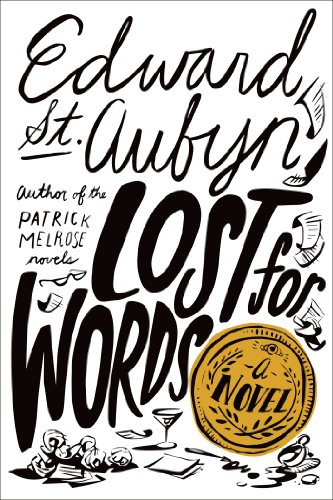

If the Melrose novels treat the many facets of pain—the birth of pain; the morbid, chemical pausing of pain; the psychological processing of pain; and the attempt to stop its intergenerational passage—St. Aubyn’s latest, Lost for Words, is a book mainly about the flight from pain through reading and writing. It is also a sporadically jaunty, often hilarious farce about a literary prize.

The self-consciously schematic plot concerns the administration of a Booker-like award called the Elysian Prize. It follows the writers who want to win, and the judges, who want the books they like to win, through the weeks leading up to the ceremony. The writers include Sam Black, a brilliant, St. Aubyn-like novelist who questions the entire enterprise of writing and publishing. Sam longs to “win his freedom from the tyranny of pain-based art.” (The book in one’s hands, one gathers, marks St. Aubyn’s bid to stop psychologically wringing himself like a rag.) Sam wonders if all good writing stems from suffering, or if writing is simply a way to make it into “a pearl in waiting.”

Sam loves Katherine Burns, who lives with her publisher. Katherine writes “the sentences of someone who trails her fingers over the furniture she admires.” She’s also a serial seducer: “She slept with the man of the moment,” but when it ended “there was nothing left.” She knows her behavior stems from the grief she feels about her father’s lack of love, but after years of seductions, her actions are out of her hands now. This kind of automation can suggest skill or addiction. In St. Aubyn’s books, one never appears without the other. For Katherine, her and Sam’s getting together would mean a manual end to her automated escapes.

Katherine has not been nominated for the prize, due to a clerical error by the man she lives with, her publisher, Alan Oaks. When she discards him, Alan gets fired, tries and fails to reunite with the wife he left for Katherine, and moves into a hotel. With no blinkering habits at hand, a lifetime’s worth of sidestepped, distressing questions reveals itself to Alan. “What had he been doing all his life? Zipping along as if the ground were not groundless.” Vanessa Shaw, an Elysian judge and Oxbridge academic, is, on the other hand, very much a person still “zipping along.” In order to dodge upsetting thoughts about her daughter, who has been hospitalized for anorexia, she always finds more busyness, no matter how keenly uninspiring.

And then there is everyone else. The novel’s other characters offer many laughs, but aren’t drawn with nearly the same empathy and sharpness as Sam, Katherine, Alan, and Vanessa. The book is like a letter written half with a calligraphy pen and half with a purple magic marker. Both parts, in their own ways, are very good. Some of the latter scenes are very, very funny. Penny Feathers, a judge as a result of being the ex-mistress of the MP who presides over the Elysian, writes a spy novel that includes the description “at ground level, the puddles had already turned into dark pools of glossy chocolate.” She sinks fully into her awesomely banal writing, and forgets to right a ruinous bit of financial misinformation she had given her daughter.

St. Aubyn’s attempt to weave the theme of pain and avoidance through his more satirical portraits doesn’t quite work. He rations his sympathy and skewering too unevenly among the characters. As one reads St. Aubyn marshaling the powers of St. Aubyn against Penny Feathers, a dim, working-class secretary, one wishes he’d picked a stronger target. But the parodies of vapid popular fiction are well-deserved and hilarious—there’s the “relevant,” over-descriptive novel about a banker in the woods; one about Alan Turing called “The Enigma Conundrum;” and a historical novel about Shakespeare, “the greatest genius in all of human history.”

Alexander Benaim is a contributing editor at the New Inquiry and a writer.