Biographers of Sylvia Plath take on a daunting task: Who could ever write as much or as well about Plath as Plath did? Plath was obsessed with re-creating her life’s story, which she not only transmuted into poetry and fiction but wrestled with in a staggering volume of personal writing. In the overflowing margins of leather-bound pocket calendars, across thousands of pages of journal entries and letters, Plath described the minutia of her days sometimes down to the hour, sparing no one from her exacting, critical eye. Plath’s story can even be divined through an incredible store of the stuff of her life. In Plath’s archives, scholars can admire her hand-drawn birthday cards or inspect the marginalia in her college textbooks, thumb through her baby album or touch the dress she wore to prom.

With this glut of evidence, and the abundance of biographies built out of it, it would be easy to feel—at times, quite literally—that no facet of Plath’s life is out of reach. Still, despite the depth of what is known about Plath, her story gets reduced again and again to one troubling, sensationalized fact: her suicide in the aftermath of her failed marriage to poet Ted Hughes. Even when discussion of Plath’s biography gets beyond her death, it often eddies around the years that Plath knew Hughes, to the neglect of the other two-thirds of her life.

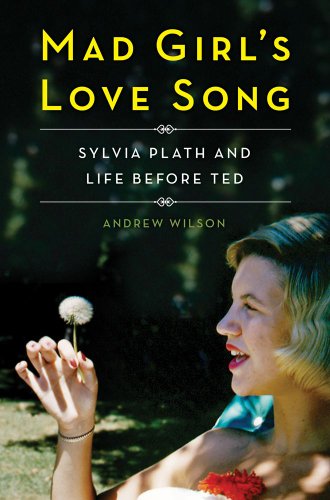

Enter Andrew Wilson’s new Plath biography, Mad Girl’s Love Song, the first book to take as its express project the offering of a portrait of Sylvia sans Ted. Of course, the book can’t dodge Hughes altogether: Wilson’s introduction begins with the tale of Plath and Hughes’s infamous meeting at a Cambridge party in 1956. Plath caught Hughes’s attention by reciting some of his poetry and the encounter culminated in a sort of explosive embrace, with Hughes ripping at Plath’s hair band and earrings and Plath biting Hughes on the cheek; she drew blood and left an angry ring of teeth marks that Hughes would carry for a month. Wilson’s account of the meeting is enough to suggest why acolytes and scholars alike get sucked into the vortex of tales about their relationship, and why stories of them as a couple crowd out stories of Plath alone. By introducing biography in this way, and by granting that Cambridge night such significance, Wilson seems at first to backpedal in his hopes of liberating Plath’s biography from Hughes’s dominating force.

But after this beginning, Wilson resists the temptation to construct the events of Plath’s life as a trajectory towards her future husband. He rewinds to tell us the story of Plath and Plath alone from the beginning, following her from suburban Massachusetts to Smith College to her Fulbright studies at Cambridge. Wilson aspires to “trace the sources of her mental instabilities and examine how a range of personal, economic, and societal factors—the real disquieting muses—conspired against her.” Where many portraits of Plath’s childhood focus on “Daddy”—Plath’s father, Otto, and the psychic aftereffects of his death—Wilson cedes some of that time to discussion of Plath’s social class. Even before she felt “socially inferior” as a scholarship student at a time when Smith was dominated by the well-to-do, Plath was sharply aware of the tangible and intangible constraints imposed by her family’s limited income. Wilson cites Plath’s repeated complaints about being shut out of the artistic advantages she saw in an upper-class lifestyle. In an example that typifies Plath’s constant worry over money, the ten-year-old poet takes it upon herself to write home from camp with a list her expenditures, down to the 40¢ she’d spent on fruit and paper dolls of Rita Hayworth and Hedy Lamarr.

Plath’s penchant for list-making takes on a new form when, thirty pages later, Wilson shows the teenage Plath cheerfully itemizing men instead of toys. At the end of high school, the much-pursued Plath used a ledger to keep track of the dizzying number of young gentlemen she was dating. According to her list, the precise figure for the period from August 1948 to August 1949 is twenty-one, with each gent also receiving a helpful star rating. Plath’s social history is so complex that I’d welcome the inclusion of a copy of the list in future editions of the book. While all of Wilson’s research is grounded in original interviews and previously unpublished materials, his attention to the stories and writings of Plath’s former lovers is of particular note. A surprising sense of loss surfaces in Wilson’s account of the feelings of Richard Sassoon, the bohemian figure Plath might have married if she hadn’t met Hughes. That loss surfaces again in his portrait of Gordon Lameyer, another young man who was something close to a fiancé before Plath rejected him; Lameyer, though scorned, remained devoted, titling his unpublished memoir Dear Sylvia.

In Wilson’s presentation of Sylvia without Ted, Plath emerges looking not exactly predatory but at least a little less like prey. And though Mad Girl’s Love Song does not radically redefine Plath, the book makes space for discussion of the complexity of the identities the poet assumed before she became Hughes’s wife. Wilson recalls a question Plath asks in her diary: “How can you be so many women to so many people, oh you strange girl?” Neither Plath nor Wilson arrive at a definitive answer, but both understand that writing is the only medium through which Plath’s fragmented identity might begin to be re-created and understood. What would Plath have thought of Mad Girl’s Love Song? I imagine her reading it keenly, nodding and underlining, hoping to parse the psychic workings of the “mad girl” behind the myth.

Related story:

Syllabus: Books on Plath

Emma Komlos-Hrobsky is an assistant editor at Tin House.