I thought he was a genius, i.e. we hated many of the same people.” — Chris Kraus, Aliens & Anorexia

For many years, I imagined aliens landing nearby and extending an offer to go home with them, where I belong. I still do. I would scarcely miss this so-called world which, having failed to notice my existence, would little note my absence. Many people, I suspect, have had such feelings. So many, in fact, that one begins to wonder if this world of ours has already been populated by aliens. What happened to all the earthlings? To feel at home in this desperate world of ours is the surest sign that one has failed to recognize it. Alienation, as Plato well understood, is the first sign of recognition—recognition of what is there, and, more importantly, of what is not. Only a snowman, Wallace Stevens wrote, is cold enough to “behold nothing that is not there, and the nothing that is.”

Aliens & Anorexia is a book about a book, or rather, about a movie, Gravity and Grace, inspired by a book, Gravity and Grace, written by the alien (nicknamed “the Martian”), mystical French philosopher Simone Weil (“rereading Weil,” writes Kraus, “I identified with the dead philosopher completely”), who fantasized about parachuting behind enemy lines during WWII, not so much to save her compatriots in France from dying as to show the Germans that the French, too, know how not to take death seriously. (“Just because things seem serious,” says the Perfect Guy to Gravity, in Kraus’s movie, “doesn’t mean they really are.”) Kraus’s book, her second novel, is a rescue mission launched to save Simone Weil after her imaginary landing, her descent from the sky; to retrieve her from the enemy. But who is the enemy? As Weil knew only too well, it wasn’t the Germans. It was (as it always is) “one’s own”: in her case, the French, the Free French, women, Jews, Catholics, philosophers. To each of these Weil (or Kraus?) was the other, the alien, as in Rachel Brenner’s diatribe against Weil, Writing as Resistance, masquerading as a book, and Francine du Plessix Gray’s war against the French philosopher, Simone Weil, masquerading as a biography (not to mention Emmanuel Levinas, Martin Buber, George Steiner, Graham Greene, I. Rabi, … Need I go on? I must. Joyce Carol Oates is in a class by herself, declaiming that “Simone Weil’s life and posthumous career are … exemplary of the spiritual vacuum of our century: the hunger to believe in virtually anyone who makes a forthright claim to be divinely guided”). Chris Kraus, the unlikeliest of soldier-saviors, has stepped in where death itself has failed, to save Weil from the likes of Brenner, du Plessix Gray, et al.; to make the world safe for aliens.

The battlefield, for Kraus, is the body. A prison, as in Plato? Perhaps. But as Weil wrote, the wall that separates two prisoners is also, when they tap on it, their means of communication. Perhaps the body is, after all, our spaceship, the only vehicle we have for transcendence. But how do we use it? “The body is a lever for salvation,” Kraus quotes Weil as saying, “but in what way? What is the right way to use it?” Kraus’s experiments with S/m pull the lever one way. (Weil’s practice of celibacy pulls in another.) Does it work? Where was she trying to go? She wants, through her person, through her body, to become impersonal (“the chief element of value in the soul is impersonality …,” Kraus quotes Weil as saying), to break through the world of gravity to a place beyond space. Commenting on Sartre’s condescending, reductive account of women in The Emotions, Kraus says that “I think emotion is like hyperspace,” through which, via a “second set of neural networks” those who “experience an intolerable situation through their bodies” (“she felt the suffering of others in her body,” Kraus says of Weil) do not become Sartre’s “manipulative cowards,” but rather travelers beyond the reach of space. “Female pain,” says Kraus, flying in Sartre’s face and in the faces of Weil’s accusers, “can be impersonal.” Not for Kraus the standard line that “like all the female anorexics and mystics [like Weil, “the anorexic philosopher,” as in a sourcebook quoted by Kraus], ‘the girl’ can only be a brat … starving for attention.”

If we’re travelers, however, aliens trapped in and trying to get out of this world of gravity, where are the signposts to guide us? We must learn to trust what chance has thrown our way as if they were signs, as if chance itself were a sign from fate. The key words, here, obviously, are “as if.” But that way lies madness. Exactly. “When you don’t know what to do,” writes Kraus, “you look for signs.” Aliens & Anorexia is itself just such a sign that chance has thrown our way, a book filled to the brim, or so it seems, with a random sequence of road signs masquerading as the autobiography of Kraus’s frustrated attempts to realize Gravity and Grace, stories of strangers, friends, lovers, heroes, liars, swindlers, failed schemes, art that died before it had a chance to live. Or is it mere chance that Gravity and Grace shows up (in the original French) in the box of random effects bequeathed to her by her lost friend, Dan Asher, when he left her; chance that her hero, Paul Thek, aimed, in his art, for a state of “decreation,” à la Weil?; chance that her oldest, closest New Zealand friend, Chev Murphy, had, in his pantheon of female heroes, a picture of Simone Weil? “The philosopher of sadness,” Kraus calls Weil, adding that, “a single moment of true sadness connects you instantly with all the suffering of the world.” And could it not be, she wonders, that “sadness is the girl-equivalent to chance?” (“Throughout the 20th century,” she writes, “chance has repeatedly recurred as the basis of artistic practice among groups of highly educated men … crocodiles in clubchairs. … Girls, on the other hand, are less reptilian …”)

Sadness, however, should not be confused with self-loathing. Kraus brings up Weil’s infamous letter of October 3, 1940 to the Minister of Education, regarding the Vichy government’s policy of denying Jews the right to teach. “The letter,” says Kraus, “is cited often as evidence of Weil’s self-loathing anti-Semitism.” Cited by whom? According to Rachel Brenner, a similar letter, dated October 18, to Xavier Vallat, Commissioner of Jewish affairs, “offers a revealing explanation of [Weil’s] celibacy,” when, in recounting her employer’s remark that her labors in the vineyard could inspire a real farmer to marry her, Weil added that “he doesn’t know … that simply because of my name I have an original defect that it would be inhuman for me to transmit to children.” Brenner’s self-confessed hatred of Weil blinds her to the fact that the letter literally drips with sarcasm.

After noting the fact that “the presumption of Jewish origin” that attaches to her name has denied her the privilege of work, she comments, deadpan, that at least having no government salary gives her “a lively feeling of satisfaction at having no part in the country’s financial difficulties.” Nevertheless, “i do not consider myself a Jew,” and “have never set foot in a synagogue,” and yet regardless of this fact, “i consider the statute concerning Jews … as being unjust and absurd.” (“one waits in vain,” writes Joyce Carol Oates, unaware, it seems, of the existence of the second letter, or the sarcasm in both, “for Weil to protest the injustice of the statute.”) After all, wrote Weil, “how can one believe that a university graduate in mathematics could harm children who study geometry by the mere fact that three of his grandparents attended a synagogue?” one must be blind indeed, or cold as a snowman, to miss the irony when Weil goes on to say that her naïve employer at the vineyard “doesn’t know … that simply because of my name I have an original defect that it would be inhuman for me to transmit to children.”

Yet for Brenner (and du Plessix Gray would enthusiastically assent), Weil’s “decision to remain sexually ‘pure’ is further amplified by a sociopsychological explanation that connects the determination to defy her female gender to her self-denial as a Jew.” for Brenner, as for du Plessix Gray, there is an indissoluble link here: “her womanhood had to be denied in order to deny her Jewish identity altogether.” repeating the absurdity that Weil considered her Jewish name a “defect” that she refused to bequeath her children, Brenner concludes that “the negation of her Jewishness and femininity are ineluctably connected.” or, as du Plessix Gray puts it, “Weil’s ‘almost hysterical repugnance for the Judaic tradition … may well have been dictated by a projection of her curious self-loathing [which “underlines [her] manipulativeness and penchant for emotional blackmail typical of many anorexics”] onto her people.’” a repugnance that may also have been influenced by her teacher, Alain, “who,” she says, “was always extremely critical of ‘this God of the Bible who is always massacring.’” (Du Plessix Gray, it seems, unlike Weil, is undisturbed by divine massacres.)

Now, there is a madness that saves, and a madness that’s simply crazy. Will anyone rescue us from the madness of Brenner and du Plessix Gray? “Why do Weil’s interpreters,” writes Kraus, “look for hidden clues when she argues … for a state of decreation? She hates herself, she can’t get fucked, she’s ugly. … [i]t must be she’s refusing food, as anorexics do, as an oblique manipulation … shedding pounds in a futile effort to erase her female body, which is the only part of her that’s irreducible and defining.” Or rather: the only part of her except her “essential Jewishness” that’s irreducible and defining. “Impossible,” says Kraus, “to accept the self-destruction of a woman as strategic.” on the contrary, “Weil’s advocacy of decreation is read as … a kind of biographic key … as evidence … of her hatred-of-her-[Jewish] body, etc.”

Kraus’s rescue operation for aliens like Weil from behind enemy lines on planet earth is a gift, if, in the end, like all good deeds, it remains—as Weil herself would be the first to insist—a fool’s errand. It is no accident that the heroes of Kraus’s film are not only fools, but lunatics. (In the movie, says Kraus, “a group of earnest lunatics wait for aliens to rescue them …”) Kraus’s attempts to rescue Weil, the parachuter manqué, the alien who never achieved lift off, the virgin, the red virgin, on board the spaceship, body—fueled by a series of (mostly abortive) sexual encounters, from imaginary phone sex, S/m, interspecies sex, sex between men and women, sex between women and women, intergalactic sex—are a joke, but a deadly serious one. After all, as the saying goes, there’s nothing funny about humor. Waiting for God, said Weil, is in the end all we can really do (though in the end, “we always do too much”), and from the lunatics in New Zealand waiting for their spaceship, and the flood, to Chris Kraus, the lover, waiting for Gavin, her partner in phone sex, to get back to her, to Chris Kraus, film maker, waiting for someone to take her movie, Weil’s idea of waiting, and no less her idea of God (or whatever she’s waiting for), is not so much realized as transformed, or metamorphosed, into something rich and strange; not the cockroaches of Kafka, but the “green and silver winged … miscegenated insects in aluminum” that Gravity, one of the heroes of Gravity & Grace, spends her time welding. Indeed, Gravity herself, no less than her friend, Grace, is a transfiguration of Weil’s Christian-platonic ideas of gravity and grace. Ideas become people, the “word” become flesh; is this not, after all, the very idea of grace?

The spaceship that never arrives in Aliens & Anorexia does after all arrive, only it’s not inside the book, but rather, the book itself. From the moment we’re on board, we’re flying through a space that only looks familiar. We’re grasping for signposts to tell us where we’re going, but we can’t read them. They’re too jumbled; they’re going by too fast. We’re on a journey, led by the narrator, who’s on a journey led by Weil, who’s waiting for God to show her where to go. Everything we see and hear is extremely familiar, and at the same time, alien. Which is only to say that Kraus is not a snowman who can see only the nothing that is here, and nothing that is not. It is a journey worth taking, if you can take it. By the strangest of means, by the most alien of paths, Chris Kraus has succeeded in saving Weil, where so many before her have failed. In truth, if I hadn’t seen it, I wouldn’t have believed it.

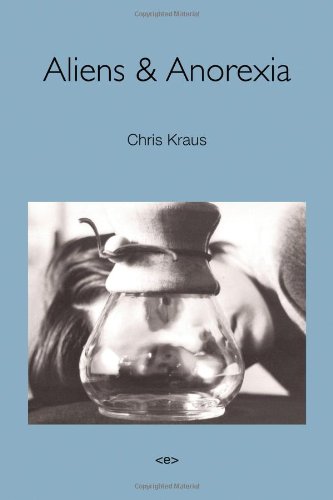

From the introduction to a new edition of Aliens & Anorexia, recently republished by Semiotext(e).