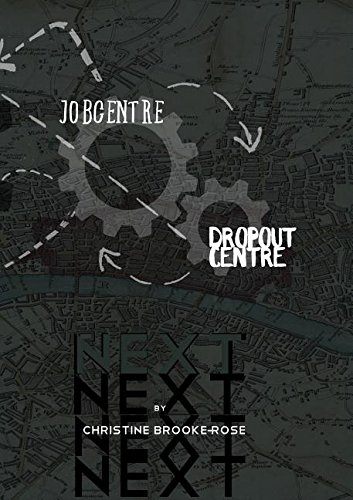

When the “linguistic escape artist” Christine Brooke-Rose died in 2012, at the age of eighty-nine, she was already a buried author, her formidable oeuvre little read or appreciated. With elements of science fiction, metafiction, and nouveau roman, her writing has been called “resplendently unreadable,” “incomprehensible and pretentious,” and simply “difficult.” Her 1998 novel Next, featuring twenty-six narrators and written without the verb “to have,” reappeared earlier this month from Verbivoracious Press, a “nanopress” dedicated to reissuing Brooke-Rose’s work.

Swiss born and Oxford educated, Brooke-Rose became an intelligence officer in the British Women’s Auxiliary Air Force during World War II, and later a freelancer for the Times Literary Supplement. Early on she published a quartet of relatively conventional, London-centric novels, including the recently reissued The Dear Deceit (inspired by the life of her absent father, a defrocked monk and petty criminal), which Muriel Spark hailed as the work of “a new George Eliot” when it appeared in 1960. Essentially juvenilia, the four London novels seem almost the work of a different author. In 1962, following a near-fatal kidney operation, Brooke-Rose made a break from her past. Newly “in touch with something else—death perhaps,” she enlisted in the avant-garde, embarking on a suite of experimental novels with one-word titles.

The first was Out, published in 1964, a “race reversal” novel in which all white people suffer from a mysterious, radiation-related illness. It was followed by Such, the internal monologue of an astrophysicist on his deathbed, which won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize—Brooke-Rose called it an adventure story, “what happens to this person who meets this girl in outer space.” In 1968, after dissolving her marriage to the Polish writer Jerzy Pietrkiewicz and decamping to France, she published Between. Written entirely without the verb “to be,” it uses several languages (left untranslated) to animate the story of a simultaneous interpreter. As Brooke-Rose couldn’t resist observing, Between preempted by a year La Disparition, which Georges Perec famously wrote without the letter e (such works are technically called lipograms). She felt that this approach illuminated a fundamental truth about language: The very act of using language, she once told an interviewer, involves a “castration. The moment we utter a sentence, we’re leaving out a lot.”

From Out onward, each of Brooke-Rose’s novels would be choreographed around some kind of restraint or excision, and each would open onto elaborately thought-out provinces where the farfetched is made still stranger by her formal experimentation. (Once invited to join the Oulipo, she apparently declined, “for fear, perhaps, of being drawn into such attractive games.”) The one-word-titled novels represent the peak of her radicalism—the last of them, Thru, published in 1975, was “a very special sort of unreadable book”, so in-group and highfalutin that even Brooke-Rose acknowledged that, “career-wise as they say,” it was a disaster. A “fiction about the fictionality of fiction,” it takes place in the group-mind of a creative-writing class and plays so daringly with typography that, on certain pages, it looks more like concrete poetry than prose. Brooke-Rose was subsequently “sacked” by her publisher on “economico-typographic grounds,” and for nine years she retired from writing fiction altogether. It was probably after Thru that she first contracted the fear of extinction that would lead her to write, in 1991, that her “only concern has been to be at least available in print, a bottle in the sea.” The crisis of undervaluation and lapse into anonymity she suffered eventually incited her to title her final collection of essays Invisible Author, and to write, by way of introduction: “I shall assume nobody has ever heard of me.” One bluntly combative passage in that 2002 book begins: “Although I was of course labeled ‘experimental’ without further detail, my topics were seldom signaled as original (which they were, if original is taken to mean not tackled before or since), indeed were seldom grasped.”

Looking back much later on her nine-year fallow period, Brooke-Rose said of the novel that preceded it: “This is the book that is always quoted when people want to say I’m difficult. I absolutely admit that Thru is difficult, very difficult…. But after Thru, you see, I changed again.” When she reemerged in 1984, it was with a novel markedly more streamlined and aware of an audience than its predecessors. Amalgamemnon, its language spun from the “brain-launderette” of a professor, Mira Enketei, is written in the oracular future tense and conditional mood (what Brooke-Rose called the “unrealized tenses”), every sentence now a hypothetical, now a projection, now a doomsday clock. Mira is a split figure: half human (a woman losing her job in a field deemed “redundant”), half prophetess—“Soon,” she warns us, “the economic system will crumble, and political economists will fly in from all over the world and poke into its smoky entrails and utter soothing prognostications and we’ll all go on as if.”

Amalgamemnon inaugurated another series of four—Brooke-Rose has a touch of the obsessive numerologist about her—known as the “Intercom Quartet,” of which the second book became the single greatest commercial success of her career. Released by Avon in a sci-fi paperback edition, Xorandor is about the politics of nuclear warfare and, more specifically, about twins who discover a talking rock that is also a computer (the title is itself a nod to binary code: Xor and Or). Brooke-Rose described it as “a distinct compromise: more plot, less play,” and she followed it up with a sequel, Verbivore, which features Mira Enketei as a cerebral radio producer made redundant (yet again) in a world where radio waves are blocked. Throughout the Intercom Quartet, Mira reappears as Brooke-Rose’s fictional doppelganger, the brilliant woman who is dismissed time and again as irrelevant, or even—as in the last novel of the sequence, 1991’s Textermination—nonexistent.

Textermination is primarily about literary canonization. It follows Emma Bovary, Holden Caulfield, Odysseus, Nathan Zuckerman, Gibreel Farishta, Sethe, Captain Ahab, Huck Finn, and Oedipa Maas (among many, many others) as they make a pilgrimage to the “Annual Convention of Prayer for Being.” They arrive at a San Francisco Hilton as supplicants before the “Reader God,” who sorts the esteemed (the “great names, great books”) from the forgotten, who can hope, at best, to be kept alive by “a small clique of scholars who ferret them out in libraries and persuade feminist and ethnic publishers to bring’m out.” The darkest fate of all is reserved for the likes of Mira Enketei, who finds herself listed on an “Index of Names Forbidden from the Canon” and knows she “can’t go on,” she “doesn’t exist.”

Here, exclusion from the canon is a fate as conclusive as death. In the Steven Millhauser story “The Disappearance of Elaine Coleman,” a woman vanishes from neglect, treated so much as if she doesn’t exist that, one day, she doesn’t—she simply disappears. Expressing a not dissimilar fear, Brooke-Rose writes in Invisible Author:

Perec told of his lipogram and got lots of attention, then and ever since, just as Eliot printed footnotes to The Waste Land and Joyce was careful to leave keys that soon overcame both the horror at “obscenity” and the mystification about meaning, keys that initiated and continue to feed the immense Joyce industry. I said nothing and was more than spared the industry: no one noticed.

Still, evaluations of Brooke-Rose by Brooke-Rose herself are there to fill the void of critical appraisal. Although she believed that any woman “who left ‘keys’ would be laughed out of court or ignored,” in Invisible Author she sets out to do just that. Its essays offer nearly as full an airing of a writer’s intentions and methods as Henry James’s prefaces, detailing the plots, lipograms, and theoretical underpinnings of each of her post-Out novels, including the late works Remake (a memoir written without an “I”), Next (the book that excludes the verb “to have,” which polyphonically relates the stories of twelve homeless Londoners), and Subscript (an attempt at the ur-story of mankind that, with a timeline spanning millennia, chronicles the journey from eukaryotic cell to early human being).

Brooke-Rose’s last novel, the autobiographical “dying diary” Life, End Of, unflinchingly indexes the physical exigencies and impossibilities that face its elderly narrator:

Oh of course blindness is nothing, thousands of people are blind, even children. But are there many both blind and very lame? The two don’t go together. A blind person needs legs to learn from touching walls and furniture; a lame person needs at least one eye to guide the zimmer or the wheelchair. The two together mean total dependence, even guiding a fork to the lips or tea to the cup.

Perhaps not since Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich has there been a fiction as obsessed with the physical body in its dying as Life, End Of—but that’s a grim pitch. Simultaneously attuned to the movement-by-movement strains of the old woman’s body and the associative leaps of her mind, the book is not only a swan song but a celebration: confessional, comedic, even fun. Brooke-Rose’s final fiction is the last hurrah of an invisible author, a party thrown by a ghost. Not for nothing did she identify a kinsman in Samuel Beckett, who also exhibited this “resolute humor in the face of despair,” as she once put it. “This kind of covering of the universe with a layer of language.”

In his elegant introduction to the wacky Verbivoracious Festschrift Volume One (released in 2014 by Verbivoracious Press), Jean-Michel Rabaté, the executor of Brooke-Rose’s estate, recounts a visit he made to the elderly author’s home in Cabrières d’Avignon. She was completing the manuscript of Life, End Of, and on the day he arrived was thinking of adding a chapter to the book. Paralyzed and blind, she asked for a pad of paper, which Rabaté gave her, along with a pen. It was no use. “I can’t write,” she told him. “It’s all covered with writing.” She then proceeded to speak out loud “a rambling letter full of sarcasm and reproach,” which she swore had been written by Joanne, “her deceased sister who continued to send her daily messages.” Rabaté, in chronicling Brooke-Rose’s last years, describes a life submerged in the past, haunted by vivid hallucinations, a life distinguished by an abundance of time. She’d had time to prepare for death, time to rehearse it in fiction—“time, an infinite time to reminisce about her past, and let all the echoes from universal literature come back to her.” Brooke-Rose is gone, leaving behind her sixteen novels, her books of criticism, her journalism, poetry, and the single short-story collection Go When You See The Green Man Walking—but then she never seemed quite present. She said it herself: “I float on phantoms.”

Alex Gortman’s work has previously appeared in the L.A. Review of Books. He is working on a novel.