Former President of Iraq Saddam Hussein’s first appearance in the historical record occurs in 1959, as a Central Intelligence Agency-sponsored would-be assassin of Iraqi Prime Minister Abd al-Karim Qasim. Years later, Hussein, after becoming Iraq’s president in 1979, would commit a number of the same missteps that finally led to Qasim’s downfall: threatening Kuwaiti sovereignty, alienating Iraq from its Arab neighbors, and not making the country’s oil reserves more accessible to Western nations. Hussein missed (literally: he was one of the triggermen) in his attempt to kill Qasim. But after Iraq’s Baath Party overthrew Qasim in 1963 (again with CIA support), Hussein began his inexorable ascent to power that began—as it does so many times in ruling-class politics, “democratic” or otherwise—with family connections.

In keeping with the historical parallels of his predecessor, Hussein also duplicated a number of Qasim’s more progressive achievements: both established national programs for education, women’s rights, housing, health care, and land redistribution. Given his justifiably terrible reputation, it can be hard to remember that Hussein initially was a relatively dedicated socialist, and that in the 1970s Iraq was among the most modernized and cosmopolitan Middle Eastern nations. Obviously, Hussein’s extensive social welfare projects are small consolation, considering the tens and even hundreds of thousands of political opponents he murdered and imprisoned during his reign. And the one million Iraqis and Iranians killed when Hussein instigated a decade-long war between the two countries. And the Kurds and Shiites whose rebellions he violently suppressed at the end of the first Gulf War.

Hussein’s first purge of political enemies occurred in 1979 when he summoned hundreds of Baath Party leaders and representatives to an assembly. During the proceedings, which Hussein filmed and distributed (footage can be found on YouTube), sixty-eight individuals in attendance were declared traitors to the party and state (their names were read by a previously tortured high-ranking Baath Party official), and led out of the room. Twenty-two of them were later executed. Other deaths soon followed as Hussein finalized a grip on power that had been growing throughout the 1970s. Yet in the two years leading up to these purges, Hussein gave speeches extolling democracy to segments of the Baath Party bureaucracy. Hussein fancied himself a political theorist and writer, and during his rule various books—including a series of romance novels—were published under his name, most of them ghostwritten. In the final months of his life, he turned more exclusively to composing poetry in his prison cell.

While Hussein was in power, copies of his books were sometimes printed in the millions. Like dictators before and after, he was a heavy-handed propagandist. But here in the United States, especially around the time of presidential elections, all political discourse feels like propaganda, and democracy the product more of financial influence than of popular sovereignty.

Thus, there’s an added resonance to the publication at this particular moment of On Democracy, which contains three Hussein speeches on the topic. Of course, it would be easy to dismiss Hussein’s democratic musings as a bad joke, and their circuitous route to publication began this way, at least according to journalist Jeff Severns Guntzel, who describes in the book’s introduction how during a visit to Baghdad doing humanitarian work before the second Gulf War an Iraqi friend gave him a collection of Hussein essays on democracy as a “gag gift,” which in turn became much less funny after Iraq was turned into an inferno by the US invasion and ongoing internecine warfare.

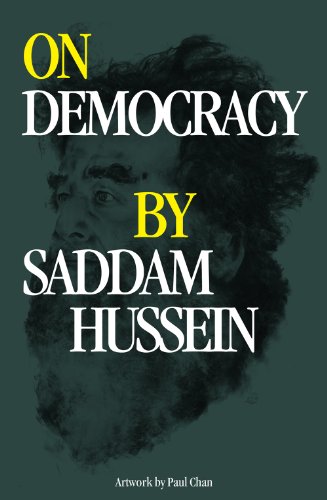

On Democracy is the project of an art book publisher. Badlands Unlimited was founded by artist Paul Chan, who spent a month in Iraq with peace-activist organization Voices in the Wilderness right before the U.S. invasion in March 2003, which is partly how Hussein’s text ended up in his hands. Throughout his career, Chan has intermingled art and politics in provocative ways. His drawing of Hussein after the latter’s capture by U.S. forces appears on the book’s front cover. In previous exhibitions, Chan has used the same charcoal-on-paper medium to render the nine Justices of the US Supreme Court who in a split decision undemocratically appointed George W. Bush president at the conclusion of the disputed 2000 election. It’s not a stretch to imagine Chan metaphorically linking Hussein’s portrait with theirs as figures who didn’t honor the will of the people, despite speaking otherwise. Along with his depiction of the bushy-bearded and subdued Iraqi leader, the book reproduces other black-and-white drawings by Chan of Hussein, the US-established Green Zone in Baghdad, Abu Ghraib, bleak landscapes, etc.

A number of these images also collage geometric patches of bright color and pattern that function in certain instances as decorative flourishes—like rhetoric—concealing darker truths. Similarly, it’s probably not surprising to discover that Hussein saw democracy as a means of winning popular consent to a pre-existing system, and certainly not the tool for ushering in a new one. Critics of current democratic systems would argue that it’s not so different in the West these days. In fact, in On Democracy, Hussein’s only critique of the country that would eventually overthrow him, although not before supplying him throughout the 1980s with substantial military and economic support (as well as personal mementos from then-President Ronald Reagan), is of “the Americans’ use of the issue of democratic freedoms against the Soviet Union and socialist states through the slogans of human rights and freedom, although in their general policies in and outside their country they strike hard at democratic freedoms and human rights as we understand them.” Post-September 11, and especially domestically, that certainly remains true. As a teenager, Hussein would have seen this process play out in the neighboring country of Iran, as the United States and Britain worked to overthrow the democratically elected Muhammad Mosaddegh in 1953.

The first two speeches included in On Democracy were given in 1977 to Baath Party planning councils; the third was delivered in 1978 to regional party leadership. During this time, Hussein more or less ruled Iraq, though Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, his cousin, was still the titular president (he became president after helping oust al-Bakr in 1979). The earliest speech suggests a general qualified enthusiasm for democracy. “Democracy: A Source of Strength for the Individual and Society” emphasizes the importance of education for societal cohesion. Hussein focuses on the role of the family, schools, and the media in assimilating the subject to the state (the use of religion came later, when Hussein felt the need to prove his Islamic credentials to the larger Arab world in the wake of his defeat in the first Gulf War). There’s very little talk of ideological indoctrination into Baath Party ideas, which in Hussein’s case seem to have been few (brute force was his “ideology” of choice); instead, there are frequent references to integration into a centralized state.

This makes sense given Iraq’s fractious and tribal society and the way that the borders drawn up by the Western powers post-World War I for the new state of Iraq enclosed a volatile mix of Sunnis, Shiites, and Kurds. But Hussein’s vision in these speeches is as much pan-Arab as nationalist, and On Democracy reads as a kind of Nasserist blueprint (which, if realized, would in turn have made Hussein leader of the Arab world): “a new sense of national and pan-Arab awareness and feelings, a belief in the socialist course, and a sense of responsibility,” he succinctly states at the beginning of the first speech. In fact, Hussein admired Nasser and spent time in Cairo for a few years after the failed assassination attempt on Qasim. But in 1977, pan-Arab supremacy for Hussein remained a dream, and perhaps merely rhetoric (as much of On Democracy might be), especially since one of his earliest acts upon assuming the presidency was to puncture any incipient solidarity by invading Iran (this after previously nixing al-Bakr’s plans for unification with Syria). That’s one of the challenges these speeches present: to what degree are they to be understood as a considered political program, to what degree are they aimed at coaxing popular consent to the Baath Party within Iraq’s fragmented demographics, and to what degree are they a smokescreen for Hussein’s ruthless personal ambition?

However, to call them rhetorical isn’t to imply that they’re particularly eloquent or persuasive, and this may be their most undemocratic quality. Rhetoric and democracy have a long, complicated, and sometimes mutually suspicious history, going back at least to the Greeks, and even in so-called “advanced democracies” there are tremendously good reasons to be skeptical about what politicians declare. Hussein isn’t so much attempting to persuade his constituencies as telling them what to do, and his ideas about democracy reflect this: “The strength that stems from democracy assumes a higher degree of adherence in carrying out orders with great accuracy and zeal.” These three speeches are littered with “should” and “must,” and the principles they encourage are almost always ethically inflected, which in politics is usually a sign of lurking demagoguery. Orderliness is encouraged (Hussein was a notorious germaphobe), and there’s much talk of obedience and discipline (along with encouragement to eat with a fork and spoon instead of one’s hands), where subservience to the state supersedes familial attachment.

The second speech collected in On Democracy is ostensibly more pro-democracy and anti-authoritarian than the first. “Democracy: A Comprehensive Conception of Life” proposes an open media, a reduction of nepotism, service to the people, and the ability to take criticism—a platform from which Hussein would take the absolute opposite tack. Yet it’s difficult not to think that Hussein wasn’t committed to aspects of this plan, however paternalistically, and if only for a short period. Hussein also argues that, “the Arab Baath Socialist Party did not and should not become an authoritarian Party,” which isn’t the hypocrisy it might appear to be, since for Hussein the party was a means, not an end. A close reading of these three speeches shows the outlines of a trajectory that uses the party to organize the country, and then applies that centralization to the solidification of personal political power—a not uncommon route for dictators to take. Nevertheless, it isn’t obvious how clear any of this was to Hussein himself, as his machinations were as much clan-based as national. In the late 1970s, much of the Baath Party’s highest leadership derived from an extended family. It’s possible that the biggest blind spot in Hussein’s political vision was not being able to see beyond the family and clan, despite his admiration for Nasser (and call for loosening family ties).

But it certainly wouldn’t be the only time Hussein didn’t take his own advice in these speeches. In fact, hindsight makes it look as if he ignores his own counsel on almost every page. This should probably make us think about the words current leaders use, but there’s something cynical in that. Instead, Hussein’s speeches force us to be aware of the framing—historical, social, rhetorical—as much as of the words themselves; in the end, that’s more valuable than falling into a dynamic of belief and disbelief. Here in the United States (and elsewhere, of course) voters are slotting into the position of simply believing, or not, what the presidential candidates say. Few things will render this dynamic of belief and disbelief more absurd than reading Saddam Hussein champion democracy. Yet that’s one of the political points of this political book published at the crest of the U.S. political season—that there need to be other forms of critical cognition besides belief. (This is part of the reason for Occupy Wall Street’s refusal, for better or for worse, to engage in standard political rhetoric in favor of a more open-ended discourse and program.)

“If we do not practice democracy, we lose you and we lose ourselves,” Hussein says in his second speech. There’s a master-slave dialectic at play here, in which, according to Hegel, the master is more dependent on the slave than the slave is on the master. It’s possible that after spending much of the 1970s in this type of relationship with the Iraqi people, Hussein decided to become the master beyond dialectics. His third speech, “Democracy: A Principled and Practical Necessity,” ends with references to “centralization with an iron will” and “strike with an iron fist,” the kind of language that doesn’t appear in the first two. He speaks of keeping the population in fear, “like a nightmare threatening their life and future.” It’s tempting to read On Democracy for these kinds of “gotcha” moments amid the paeans to egalitarianism, although that gets depressing fast. So, too, does taking the ideas in these speeches seriously, given what history has revealed. Will reading them make people any more aware of the abuses occurring in democracies closer to home? It’s possible. Will it lead to a better understanding of how the idea of democracy gets appropriated for non-democratic purposes? That seems a little more likely.

Early in On Democracy, Hussein compares the ruler and the educator to an artist shaping society and its subjects. In “Saddam Hussein and the State As Sculpture,” one of two essays closing the book, Negar Azimi describes how the cultural projects initiated by Hussein increasingly served his self-aggrandizement. In the 1970s, Hussein built museums; in the 1980s, he constructed palaces. In the 1970s, he oversaw a UNESCO-recognized literacy program; in the 1980s, his biography was required reading in school. This sense of personal grandeur expanded in proportion with threats to Hussein’s rule: there was a serious assassination attempt in 1982, and he gradually lost the trust of segments of his military during the long war with Iran, and more fully after the first Gulf War. It’s possible that had Hussein continued to pursue the Nasserist program he gestures at in On Democracy, the United States may have sought to topple him before 1991. Instead, it played both sides against each other in the Iraq-Iran war that devastated the two countries. It’s a very sordid history for all parties involved, the repercussions of which continue into the present, making On Democracy more than simply a curiosity.