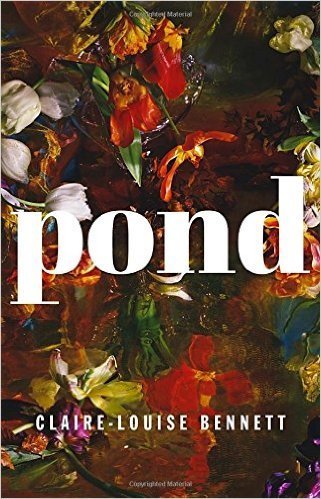

“Regrettably I don’t think my first language can be written down at all,” explains the unnamed narrator of Claire-Louise Bennett’s debut novel Pond, which leaves us in the idle hands of a woman who has abandoned academe and retreated, alone, to a stone cottage in the Irish countryside. Here, she has given herself over to a ripe compulsion to grammatize her experience of the world. “I’m not sure it can be made external you see. I think it has to stay where it is; simmering in the elastic gloom betwixt my flickering organs.” For the time being, she writes in English with a warped dexterity that achieves startling descriptions of an “avuncular” sky, a car park that smells “exclusively of dishcloths,” and wanting Christmas to “slump backwards into its shambolic velvet envelope.” When she voices words, she tells us, they usually become “misshapen” and not at all what she had in mind. Yet she can’t help but anticipate their “alien and absurd” results, some of which are chronicled in this twenty-part miscellany. Pond concerns itself with the lot of an intense intellect as she nurses the bruises from a falling-out with the academy and constructs a world in which her irksome relationships with language and structure become her greatest assets.

Our recluse luxuriates in the textures of quotidian life, cataloguing meals prepared and baths taken, charting ill-starred affairs, and, tuned in to some transcendental bandwidth, recording the raging of storms and “the woodpigeon’s wings whack[ing] through the middle branches of an ivy-clad beech tree and the starlings on the wires overhead, and the seagulls and swifts much higher still.” She suspects that her “poeticized rendering[s]” are wrought from wanting to sound “perspicacious and grown-up, and very aware of how one’s life develops according to the uncanny distillation of subtle kairotic shifts.” She is self-aware and jaded, but her jadedness is noncommittal. Her observations swing from enthrallment to wry misanthropy: She swoons over the word “cantilevered,” but she is also delighted to fling worms at people. There’s ire and bitterness, too. Though the specifics of the narrator’s circumstances are never revealed, we learn that the academy rebuffed her work on depictions of love in literature, which aimed to demonstrate that “the desire to come apart irrevocably will always be as strong, if not stronger, than the drive to establish oneself.”

The book revolves around these competing obsessions—love, or rather, men, and her place in academia—even as it busies itself with keeping them at bay. She approaches each topic wielding a linguistic shiv. She rarely discusses the substantial time she dedicated to producing “yet another overwrought academic abstract.” Instead, she ascribes great importance to sundry domestic activities, which she vividly and regularly inventories. She admits it cheers her up to “imagine ashen professors stretching viscous strings of bird shit across thin slices of toast, which naturally they’d hold slightly higher than necessary between the pincers of their spindling waxen fingers.” Men riddle Pond’s pages, but we never learn their names. We are told the narrator can only muster interest in them when she is inebriated. Rather, she is aroused by “inexplicable disdain,” and the most excitement she demonstrates is when she is alone, penning erotic emails for the first time, or when—in a passage as radical and gutting as any I’ve read on sexuality—she anticipates being raped by a stranger in a field.

Pond is, perhaps, a performance of the narrator’s dissertation: It is wholly invested in the business of coming apart, in the urge toward entropy. Sometimes, her desire to come apart is self-fracturing, and she raves with a hot, obscuring near-madness. Other times, that desire severs her from others, and the result is unchecked narcissism. In a chapter called “Finishing Touch,” she decides to throw a party so that she can attempt a view of her home through the eyes of her guests: After they ask to explore the upstairs, she plans to sneak up behind them to track exactly what they have seen.

The novel never departs from the subjective, and only really leaves the present in the first and final chapters, each pill-sized, in which our narrator returns to childhood, accessing the past through the collective “we” in the first instance, and via the third person in the last. The formal mechanics of these bookends mark the protagonist’s distance from her young self, as she sat on the “cusp of female individuation.” In the first story, she climbs over a wall to sleep in the garden of a man she thinks is handsome, leaving her friends to play kid games. In this moment, the camaraderie of girls, and the shared fantasy they can together inhabit, is cracked by the individualism of sexuality, the impetus to define oneself against others, to be more or less. In the final chapter, the narrator imagines shattering an apple against a house and “the awful flat sound it makes when it hits the wall and falls apart,” conceding “that her imaginings had to become more cautious, more subtle.” These impressions, of breaking away from the protections of youth and of early attempts at self-restraint, bracket our narrator’s seclusion, melancholically suggesting its inevitability.

Coming apart, or rather, being apart, is of course a theme underscored by the allusion in Bennett’s title to Thoreau’s treatise on solitude. But many of the naturalist-seeming passages here don’t translate into direct observations, but rather reveal the reaches of her stirred imagination. Noticing a pile of reeds that will thatch her roof, she muses, “I liked to think about all the little fishes that had nudged around and prodded at the reeds here and there. And I liked to think about the bigger fish, pike for example, that had occasionally swished past deep down and set them off nervously swaying, for miles and miles and miles perhaps. And the adrenalised coots spun out by the whirlpool of their own incessant rubbernecking and the hot headed moorhens zigzagging to and fro. And the swans’ flotilla nests resplendent with marbled eggs. And the sly-bones heron in a world of his own. And the skaters and the midges and the boatmen and the dragonflies and the snails and the spawn, and who knows what else the susurrant reeds are raided with.” In her isolation, Bennett’s narrator is not after an unbridled communion with nature so much as with her own ravenous mind, and with the process that channels perception into reason or obscurity.

Thoreau described Walden as “a mirror in which all impurity presented to it sinks, swept and dusted by the sun’s hazy brush.” Bennett’s titular pond rarely appears in her story. When it does, it carries little of the cleansing powers of Walden. It’s a wimpy thing that will likely be outlived by a plywood sign sited nearby that irritatingly announces its presence: pond. When the narrator has something she needs “to get rid of fast, a broken, precious thing,” she carries it to the puddle. “I dropped it into the water and it did not sink and go on sinking. It just sort of wedged itself and was horribly visible.” Impurities, of a material or psychological sort, persist, the author reminds us, even if they have been swallowed by Walden’s crystal surface or hidden away in a rural haven. Bennett has found disarming clarity in making them horribly visible.

Annie Godfrey Larmon is a writer, editor, and curator based in New York.