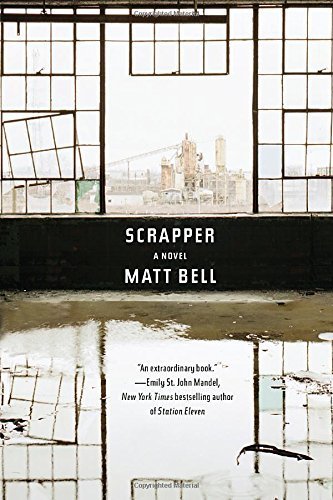

The very title of this novel announces a departure for Matt Bell. Scrapper—with its homely brevity and flat vowels—stands in striking contrast to the Biblical roll of Bell’s 2013 In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods. So too, more substantial elements in the new book reveal that its young author is going for something different. The house and lake of the previous novel had no fixed address, unfolding in a nightmare. But Scrapper at once places us in contemporary Detroit, “fifty years an American wreck.” A handful of chapters visit elsewhere, but the stay is always brief and the locale definite. In the most moving of Scrapper’s brief layovers, it’s the ghost town next to the Chernobyl nuclear plant.

Settings such as those, of course, insure that this story has nightmares of its own. Indeed, the mood is gloomy—I count only one bona-fide laugh line—and the bad news by no means limited to public tragedies like Chernobyl.

The wreck of Detroit has given rise to a new job title, a “scrapper,” who harvests the organs of dead buildings. Their wires and pipes can fetch a decent price. The profession proves well-suited to Bell’s style, which finds odd angles on the ordinary, at times turning it inside out: “A house changed after he saw its walls as containers. He began to understand the arcane layouts of the worlds behind walls.” That “he” is our protagonist, Kelly, a newcomer in town—not to say a refugee. He’s up from the South, and by no means work-shy, but throughout, man’s worldly goods never amount to much more than a toolbox and a pickup. The milieu recalls Preparation for the Next Life, by Atticus Lish, last year’s compelling exploration of threadbare urban lives, and Bell’s novel stands up to the comparison admirably. The mean streets of Scrapper may be rendered with fancier rhetoric than that of Preparation, but the vision never prettifies the ravages of the American hardscrabble. For Kelly, “the only true safety was the deepest kind of loneliness.”

As the novel opens he’s “not yet again living any real life, just wallowing in the aftermath of terrible error.” The nature of the error, and the likelihood of redemption, remain long in shadow. We go roughly halfway into Scrapper before learning, even, that Kelly’s thirty-four. By that time, the woman and stepson he betrayed down South don’t haunt him nearly as much as the steep challenge of remaking himself up North. The trouble starts out as anything but: the scrapper plays the hero, rescuing the trapped young Daniel, a kidnap victim (the crime leads to further intrigue, but no one would mistake this story for a whodunit). Kelly’s luck would seem to bode well, and he does enjoy a few pick-me-ups. Yet even as the protagonist tries on better notions of self, as he deems himself a “salvor,” he feels more drawn to violence and, in time, vigilante justice. The protagonist seeks “to find his limits”; he joins a fight club.

Now the word scrapper reveals its second meaning (just as names keep proving slippery). The boxing passages achieve a masterful ferocity, for both physicality and sound: “With every strike his quiet mind exploded into sound. . . . The brain suddenly a size too big for the shell.” While the intensity is Bell’s, the mania is Kelly’s. The “responsibility of the good man,” amid these ruins, drives him to extremes. He can grasp the danger, the way “any responsibility taken far enough inevitably risked an atrocity,” and yet he goes on taking things far and farther.

Now, in a review, the exact nature of Scrapper’s final “atrocity” has to remain a mystery. Still, I can say that both those involved, a teenage boy and the middle-aged Kelly, demonstrate decidedly ambiguous morality. Indeed, their final flailing resembles that of Daniel’s kidnapper, who speaks up briefly, now and again, over the second half. His chapters occur in second person (the sign of a sociopath, perhaps?) and certainly prove him the greater evil. Nonetheless, the horrors perpetrated by the kidnapper remain cloaked in euphemism, and what justice comes for him arrives out of left field.

These murky resolutions are in part a result of Bell’s style. His penchant for indirection can enable fine surprises, for instance upending expectations about race, in his Motown setting. In other cases, however, withholding or skewing basic information creates unnecessary muddle. The problem isn’t just a matter of sentence-level overreach, such as when Scrapper dolls up a handgun with a “halo of deathly want.” At their worst, such effects reduce plotting to teasing. Kelly’s misdeeds in the South, for instance, emerge only in vague allusions, so his remorse never sinks the hook.

Critics of Bell’s first novel raised a similar complaint, claiming its humanity was suffocated under the author’s determination to make a fable out of everything. Myself, I thought better of In the House—but better still of a more controlled earlier fiction, the small-press novella Cataclysm Baby (2012). As for Scrapper, I’d argue it outdoes any of the author’s efforts to date. The weaknesses I’ve just cited seem actually, as with many a fine book, a by-product of its defining strength.

Insofar as the mysteries leave dangling ends, insofar as the fates of the major players feel uncertain, it seems fitting for the novel’s world, splintered and undone. In scrapper America, every unfortunate must scavenge his own lonesome way. In Kelly’s case, his closest brush with a better outcome comes via a newfound lover, a woman named Jackie, yet she too knows better than to nurse expectations beyond the minimal. Her bad limp, Jackie declares flatly, is only an early symptom of a disease soon to kill her. What warmth she and Kelly share during his occasional sleepovers is only “the inexplicable unspeakable elation that everything wrong in their lives had not brought them to ruin.” Scrapper distinguishes itself most by how skillfully it places us all in that ruin.

John Domini’s latest book is The Sea-God’s Herb, selected criticism, and he has a book of stories coming in 2016.