New York City is built on the backs of earnest, reticent, frugal, and ambitious Midwesterners. These are “the settlers” who make up the “Third New York” immortalized in E.B. White’s Here Is New York. Look in the right places and they seem to be everywhere: Minnesotans ordering the cheapest beers on draft at East Village bars, dumpster-diving South Dakotans, Iowans doctoring up ramen with cheap vegetables sold on Chinatown sidewalks. The Third New Yorker, White writes, “accounts for New York’s high-strung disposition, its poetical deportment, its dedication to the arts, and its incomparable achievements.”

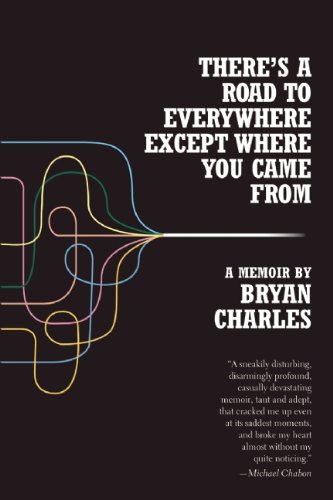

Bryan Charles, in There’s a Road to Everywhere Except Where You Came From, his potent, touching, slow burn of a memoir, plays a role straight out of the E.B. White Third New York Central Casting Agency, that of the “boy arriving from the Corn Belt with a manuscript in his suitcase and a pain in his heart.” In Charles’s case it is a 25-hour train ride from Kalamazoo to Penn Station, where he arrives in October 1998 with “two bags of clothes and a banker’s box full of papers.” A girl-crazy, middle-class college grad who finds solace in indie rock, Charles, the author of a novel (Grab on to Me Tightly as if I Knew the Way) and a short book about Pavement’s album Wowee Zowee, aches to make his mark in the literary world and support himself while doing it.

“I want to achieve extraordinary things,” he writes with no sense of entitlement but also no clue how to come up with a game plan. His mother offers to wire him money and she places calls to find him a job in publishing, an endless source of irritation for the independent-minded Charles, who spends his days sending out resumes (since this is the ’90s, he does so using a fax machine).

He does draw on a Kalamazooan support network—a shared apartment in Brooklyn’s Greenpoint with college friends and Erin, his on- and off-again girlfriend who in many ways is the soul of the story. (And who also, arguably, inspires the worst line of the book: “The past was alive in the shape of her body and dead gods spoke to me through her tongue and mouth.”) It is also during this time that he meets his father for brunch in the Upper West Side apartment of his Dad’s younger girlfriend, who announces that she’s pregnant. Throughout There’s a Road, Charles keeps his feelings close to the vest, but this scene marks the first time we see both an emotional outpouring and immediate self-flagellation. “I hated myself for crying over this shit,” he writes.

Eventually, Charles does find his footing, at least in the day gig department. He works in the mysterious position of “marketing writer” on Wall Street, which seems to encompass endless edits of mutual-fund brochures and getting paid “righteous coin” for doing it. He falls upward salary- and building-wise, landing from a small investment firm to a job at Morgan Stanley in the World Trade Center’s South Tower. Charles’s crisp writing sends portentous chills with this description of the view from the 70th floor on the day of his interview: “It was dark and clear out and there was Manhattan like an architect’s model, lights spread out below bleeding north into the cluster of tall Midtown buildings—but even those looked small from up here, the Empire State Building roughly the size of my pinky, the whole scene framed by purple sky and pale clouds.”

Even with the specter of what we all know is going to happen downtown stalking the book, Charles does a good job of holding back the tension. He goes down to the WTC mall’s Borders bookstore and seethes with jealousy and want as he looks at the new-releases table, “checking author bios for birth years and schools.” Gore Vidal famously wrote, “Every time a friend succeeds, I die a little,” and Charles is admirably honest about how he dies with envy of other writers’ success, particularly Baines, a new friend whose easy literary success seems to elude Charles. He turns almost mute meeting Richard Ford, and finds Jonathan Franzen “pretentious” when he introduces his hero Don DeLillo at the 92nd Street Y.

There are certain points when it might be not so far off the mark for the reader to think of Charles, at least the Bryan Charles on the page, as quite the cocksman, a hard-drinking, Weezer-listening version of Mad Men’s Don Draper. “The women save you,” he writes to himself. “You fantasize about fucking virtually every woman you see.” He casts his male gaze wide. A new literary star, Zadie Smith, is described as a “stone fox.” He theorizes on the presentation of one co-worker’s décolletage, and falls in love from afar with Jasmine, a broker’s assistant from the 72nd floor, an African American woman with whom he never directly communicates. “It was a shelf,” he writes of Jasmine’s badonkadonk. “You could’ve set all six volumes of Proust on it.”

He does OK in the non-fantasy department as well. A semi-scandalous affair with a co-worker reaches its height on a Puerto Rico work jaunt, where he gets laid to the strains of the Flashdance theme wafting in from a resort cover band. He flirts with an ex-student from his substitute-teaching days on one of his many trips back home. Charles is self-aware enough on the page to interrogate these yearnings. “I believed all my bullshit,” he writes after he proposes to start an affair with a high-school friend back home. “Give me old moments back. Let me live out of time. Shoot me a little something for these troubles, the endless sameness of days.”

Throughout, Charles moves from wide-eyed Middle American to East Coast hipster. And we see his tastes change through his eye for 90s period-piece detail, which captures the charm of a fin de siècle Big Apple. While faxing resumes, he’s preoccupied by Jennifer Love Hewitt as a still-potent sex symbol. He meets Moby at a party in the Lower East Side and is starstruck. Later, he lands his name on the invite list to a Guided by Voices show. His walks along Bedford Avenue through McCarren Park grow more confident. He meets friends for beers at Enid’s and Pete’s Candy Store. And who among us has not experienced in our twenties the “struggling-musician creep” neighbor who spends hours “playing the same idiotic funk bass line over and over again”?

Of course, where many memoirs fall under strain to come up with a lesson or epiphany, Charles has in his back pocket one of the world’s most apocalyptic recent events to tie up his story lines, and it is to the book’s credit that, despite it being almost a decade since September 11, the events are described with both jarring emotional effect and remarkable constraint. The turn both disrupts and solidifies many of the ideas Charles presents in his first two acts, and is also where his style choices—short sentences and paragraphs, plainspoken description, the non-mainstream choice of presenting dialogue after long dashes as opposed to full-on quotations—pay off in spades. From the first loud boom and floor tremble, it’s hard to stop reading.

“DO NOT LOOK UP. WHATEVER YOU DO, DO NOT LOOK UP,” he hears from a police bullhorn, as he makes his way outside from his walk downstairs. “I didn’t die in that bullshit,” he tells Erin on the phone. “Fuck this shit. I can’t live here anymore. I can’t live in a place where something like this can happen. I’m getting the fuck out of here. I’m leaving.” He retrieves a succession of thirty-five voicemails—“some of my friends thought they were addressing a dead man”—and later his mother arranges for an interview with the Kalamazoo Gazette and a couple of network affiliates. He’s again irked by his mother’s stage-parent aspirations, but eventually comes to the conclusion that he’s finally found a story he and few others can tell. He is no longer the wannabe voyeur attending the reading or concert; it is, as his mother tells him, his turn to tell the story.

The event haunts and focuses Charles at the same time. “Something was working toward me,” he writes in the days that follow. “I sensed my life would end suddenly, violently, prematurely.” At last he feels he has something those in the literary mainstream lack: experience. “What I read enraged me,” he writes after skimming a post-9/11 New Yorker in a Hudson News shop in the Port Authority bus terminal. “All those geeks could do in the face of this was fashion their impotent similes. Now they were the ones with their faces pressed to the glass.”

Charles also confesses to hoping his story was somehow even more dramatic and singular than it already is. “A rumor made the rounds about a guy high up in one of the towers who rode the building down as it collapsed and lived,” Charles writes. Perhaps he realizes his proprietary feelings about the tragedy have gone too far. “The story was fake but why couldn’t it have been real and why couldn’t I have been him?” Charles may not have descended from on high atop a wave of wreckage, but his story is real. His personal failings and weaknesses and jealousies underscore Charles in his role as hipster anti-hero of a bygone era.

Daniel Nester is the author of How to Be Inappropriate (Soft Skull Press, 2009).