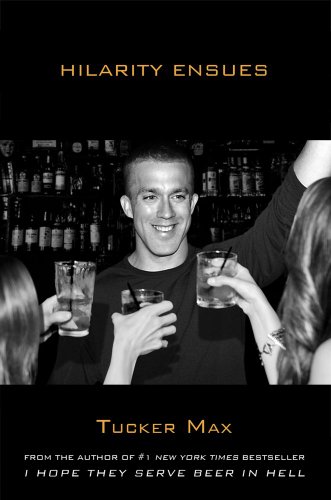

I have a bad habit. (No it’s not that I read Tucker Max’s books for pleasure.) My bad habit is that I often begin books by taking a peek at the ending. The best test of a book is not the seduction of a well-planned first sentence; it is how well the book satisfies expectations at the bitter end. By this measure, Tucker Max’s third book, Hilarity Ensues, is a great read. The epilogue begins, “When I got to the literary world, it was like a great big pussy, just waiting to get fucked—and I stepped up and fucked the ever loving shit out of it.”

I was sold—not on the book’s literary value, per se, but on how it highlights Max’s firm belief that he is on the vanguard of a new type of book culture. Max may be the ultimate example of a post-book literature, one in which books begin as digital artifacts rather than print ones, example of which include bestsellers you’ve probably heard about (i.e., E.L. James’s now inescapable Fifty Shades Trilogy) and some you probably haven’t (such as Hugh Howey’s Wool Omnibus). Max’s book certainly offers a preview of the forces exerting a magnetic pull on publishing in our post-codex, iPad age; I’d risk the argument that there are worthwhile lessons here that are applicable to all writing.

In any event, Max’s summary thoughts may mark the end of not just his latest book but his reign over the entire literary school known as “fratire” and the success it has brought him. A designation of recent vintage, fratire is a strain of virulently misogynist, politically incorrect, supposed non-fiction books, usually written in the first person. Often drawing from projects incubated on the internet, the genre has regularly placed titles on old fashioned best seller lists since the middle aughts. Very regularly in the case of Max’s work. In my imagination, most of these books are sold at college bookstores or in airports, where I first noticed him on the shelves. (Note: You are excused for not knowing what fratire is unless you are in the publishing industry or have attended an American college in the 21st century, in which case you had better.)

Max has said that Hilarity Ensues is his final contribution to the sub-genre, and has been selling his shift in sensibility pretty damn hard. In January, Forbes ran a profile in which he revealed he is in four-days-a-week psychoanalysis; that his books reflected a long-time “dissociative state”; and that he is now a regular yoga-practitioner and kombucha-drinker who is dating a nurse. To punctuate this 180 degree shift, he started a new site, TuckerMax.me (assumedly the “real” me), and seems to be establishing credentials for a second career as a mentor and personal-advice guru.

I can already guess: You’re not impressed.

It is tempting to dismiss Max as an idiot, a provocateur, or simply an asshole. Indeed, that’s a designation he embraces. The most prominent sentence on the eponymous |tuckermax.com|website| where he built his franchise is the phrase “My name is Tucker Max, and I am an asshole” in 18 point type. Moreover, he’s made this fact abundantly clear when he’s let his books segue into real life. In April of this year, there was a minor hubbub among online tabloids when he revealed a 2011 offer to donate $500,000 to Planned Parenthood, a donation that came with the caveat that they’d have to name an abortion clinic after him. This was from a man who once sent a Tweet to his 300,000 followers stating, “Planned Parenthood would be cooler if it was a giant flight of stairs, w/someone pushing girls down, like a water park slide.” Recognizing a press stunt and potential PR disaster, the organization turned him down. In the faux-controversy that followed in The Daily Beast, the Huffington Post, et. al., he demonstrated his pro-choice bona fides by stating he’d paid for “between 3 and 5” abortions for previous sexual conquests. Max has an optimistic take on what such behavior says about him. His second book was called Assholes Finish First.

His oeuvre delivers on the promise of assholery, less so of winning. For example, almost every woman depicted is viewed through the lens of a “female rating system” that starts at “wildebeest” and tops out at “super hottie.” There’s more at work here, though, than simple misogyny. Let’s take a closer look at the first lines of the books, each of which betray a slightly more nuanced portrait of the author as someone who hates not only women but himself. From Hilarity Ensues: “I worked in Cancun, Mexico for six full weeks during my second year at Duke Law School.” Or, from his debut, I Hope They Serve Beer in Hell: “I used to think that Red Bull was the most destructive invention of the past 50 years. I was wrong. Red Bull’s title has been usurped by the portable alcohol breathalyzer.” What follows is a story about Max’s efforts to achieve a blood alcohol content level of .20. A BAC of .08 is legally drunk. Apparently a BAC of .35 kills most people. In the telling, his BAC tops out at .22. This is a Charlie Sheen-esque, demonstratively hashtagged variety of #winning.

At heart, the author is (or was) a fratty nihilist, and the self-portrait he paints is of an eager-to-offend guy filled with demons and driven to self-abnegation and the dark truths about the human condition found therein. The fictional analog that comes to mind is Patrick Bateman, the investment banking serial killer in Brett Easton Ellis’s American Psycho. Or, if you focus on the genre-fiction elements, a character less akin to John Belushi in the frat comedy classic Animal House than to the real life John Belushi.

*

Imagine, for a moment, a sewer in which small and glittering jewels of insight are hidden. I entered Max’s world of fratire with such visions. And so I read on. Dismissal is a convenient way not to contend with his popularity, but doing so risks ignoring a cultural touchstone. Sure you can choose not to have an opinion on phenomenon like the Kardashians, Lady Gaga, and reality television, but if you don’t understand what they represent, one risks not understanding the culture at large—and, more specifically in the case of Tucker Max, a portent of fundamental shifts in book culture.

It’s important to know his works have sold millions of copies, most notably I Hope They Serve Beer in Hell, which appeared annually on the New York Times Best Seller List between 2006 and 2009. It moved almost a half-million copies in 2009 alone. His latest book debuted on those charts at number two and, to this day, one of his three books is generally positioned somewhere on the Times’ lists.

How did he get there? In the fall of 2010, on the same day his second book was published by mainstream publisher Simon & Shuster, Max laid out his origin story in a post on the blog of Timothy Ferriss, the equally popular, considerably less reviled, but similarly internet-driven author of The 4-Hour Worksweek, The 4-Hour Body, and the forthcoming The 4-Hour Chef. The timeline starts out typically enough:

– Early 2002: Tried to get my book, I Hope They Serve Beer In Hell, published. Sent the core stories from the book to every publisher, literary agent, magazine and newspaper in the country. At least 500 query letters, maybe closer to 1000. I was rejected by 100% of them. Literally every single one, without exception.

A common strain in classic “making it” stories is persistence, persistence, persistence until the gatekeepers recognize true genius (or impossible-to-ignore success), thereby allowing the outsider into the club. This is where Tucker Max diverges from tradition:

– Late 2002: With no other option, I learned HTML and put my stories up on a website, TuckerMax.com.

– May 2003: The site’s popularity exploded (on the internet), and the publishers came back to me, asking to publish my book.

– January 2006: Book came out, got zero media coverage and zero advertising support, but still hit the NY Times Bestseller List immediately because of the support of the fan base I’d cultivated through my website.

– October 2009: Reached #1 on the list, more than three years after it came out.

What differentiates Max from other do-it-yourself success stories is that his deal with a major publisher was less a means of buying into legitimacy than a straight distribution play to get into those aforementioned airports. Evidently he now has a strong enough track record that he’s returned to self-publishing. Hilarity Ensues came out on his own Blue Heeler Books imprint. This is not Christopher Paolini’s Eragon, or Rick Warren’s Purpose Driven Life. It is more like Deep Throat at the local multiplex.

*

In other words, what makes Max worthy of case study treatment is his ability to take a very marginal set of ideas to a very broad audience. I think there are two reasons that this guy, his work, and his fame are really fascinating.

First there is Max’s relative and continuing obscurity. Let me put it this way: Had you heard of him before reading this review? More to the point, have you read him? Do you know anyone that has? In a way, his work shares many characteristics with other documents of contemporary niche culture. What Dave Hickey’s Air Guitar is to the art world, what Michael Azerrad’s This Band Could Be Your Life is to indie musicians, and what Slavoj Žižek is to trendy public intellectuals, Max is to hard partying, middle-of-the-road college students. His writings serve as a kind of mass-market samizdat, presenting an alternative to the boredom of work-a-day America. Certainly his books contain the same kind of “had to be there” topical specificity as those other writers. Familiarity with “party hard” touchstones like Cancun, Snoop Dogg, and Discovery channel’s The Deadliest Catch show are essential to enjoying Max’s latest effort. I think Max’s success is simply due to the fact that the world contains a greater number of frustrated college students who want to cut loose but are destined to work in cubicles forever than it does aspirants to the hallowed halls of indie rock, art and philosophy. What explains Max’s popularity, then, is not mainstream curb appeal or a lowest-common-denominator approach but a naturally enormous demographic and his extremely effective method of speaking to them. If you need proof that these are resolutely literary works, when Max produced a film version of his first book, it reportedly grossed .4 million against a million dollar budget, partially self-financed. Whoops.

Point being: Anyone who desires to write for a passionate audience of fellow travelers would be smart to emulate Max’s example.

And that brings me to the second interesting thing about Max: While he may be terrible at crossover pop culture, he has a fantastic understanding of how writing works in the digital age. Take, for example, how he discovered the power of the internet. Max—who graduated from the University of Chicago and Duke Law School—was seeking a summer associate job at a Silicon Valley law firm circa 2000. In an effort to drive up his own salary, he made a series of false postings to a legal industry message board, essentially having a conversation with himself, each post citing ever more ludicrous sums being offered by bay area firms. Apropos of the rah-rah pre-bubble internet culture, this hucksterism worked. (Lesson #1: Online identity is malleable, especially pre-Facebook.)

After he got the job, he discovered the phenomenon of “going viral.” He emailed a number of friends a simple narrative about a drunken night at a law firm party-cum-auction and the mortification of the firm’s hiring partner. A few days later he was fired, but the email was subsequently forwarded around to dozens of firms, like a giant game of telephone, only with Max’s name firmly attached. (Lesson #2: The internet is good at spreading two kinds of information: vague rumors and endlessly replicable, digital facts.) The story in which he reveals these a-ha moments is one of his earliest—something spelled out because each of Max’s early stories is given two datelines, when it “Occurred” and when it was “Written.” This one was titled “The Now Infamous Tucker Max Charity Auction Debacle,” and he notes therein: “That email went around the world, several times, and at last count went through like 100+ firms.” The emphasis is mine, to point out his efforts at stretching truth into a creation myth. Lesson #3 (I’ll call this the “truthiness” thesis): On the internet you’re as famous and successful as you can convince people you are—something made possible by an environment where reality is determined not by the wisdom of crowds but by illusions traveling peer-by-peer.

Having proved he could create memes that travel, and that he could gin up buzz from ether, Max spent the next half-decade developing his writing career and his very real talent. While he has questionable moral fiber, he has a very admirable grasp on sentence structure and narrative technique. Here are Timothy Ferris’s thoughts on Max’s success:

“There are many contributing factors, but I believe one of the largest is overlooked: he has a clear voice. Good writing does not mean becoming a grammarian or using big words. It means telling stories worth telling (in Tucker’s case) or sharing lessons worth learning (in my case), and doing it with a compelling and consistent voice. Tucker wrote many of his best stories while pretending to write an email to his closest friends. He knew that if he drifted or postured as a ‘writer’ for even one paragraph, they’d hit delete and move on. It was this believable (and authentic) intimacy that hooked people.”

What’s comforting to consider here is that maybe Max’s fans aren’t attracted to his worldview, but the simple readability of his prose. Lesson #4: Clarity of meaning is a cardinal virtue amid the distractions of the internet.

It’s trendy to say that writing is of diminished importance in our increasingly digital age. For example, media theorist Douglas Rushkoff downplays the value of blogging and other avenues of writerly online expression in his latest manifesto, Program or Be Programmed. Instead, he urges individuals to pick up the tools of programming for fear of being lost in the maelstrom of the digital world, offering “ten commandments for a digital age.”

Really, though, I think all the online medium requires is succinctness. I’m quite sure the web will continue to shift our expectations of community, personality, even physical presence. Essentially modern life is becoming more of an abstraction. What Max shows is that one great way to get a foothold within that abstraction is to cut out the crap. I can envision him boiling down Rushkoff’s “ten commandments” into a short aphorism: “Code or die.” And Max’s career, which has certainly made him millions, suggests a further addendum to that maxim: “Write well and you won’t have to.

Alec Hanley Bemis (alechanleybemis.com) is a writer, entrepreneur, and creative enabler who founded the Brassland label and manages various musicians.