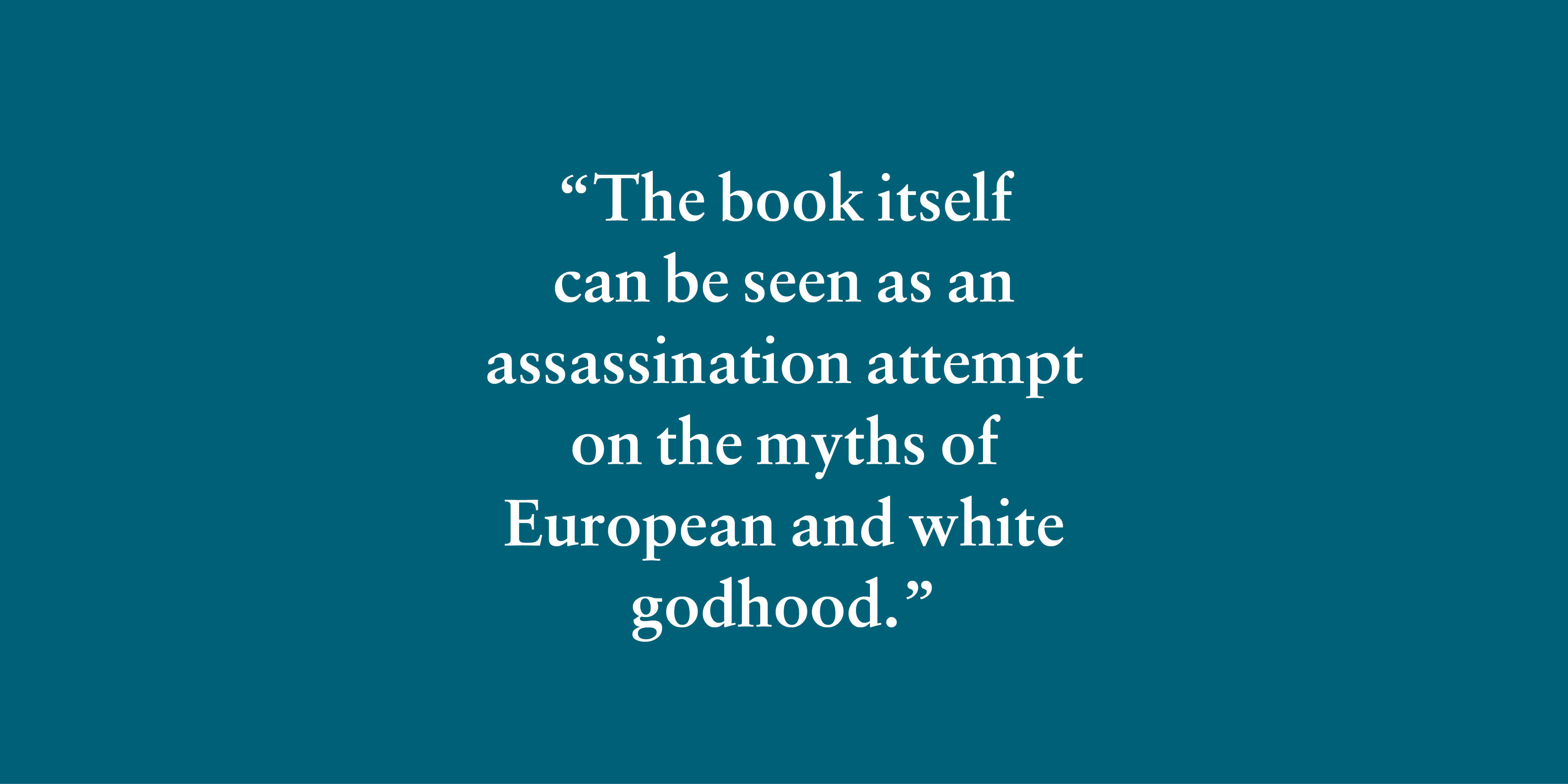

ZORA NEALE HURSTON’S LITERARY STATURE is no longer in dispute, yet people are still trying to put her into a box. “Do you think she was a libertarian?” someone once asked me. For whatever reason, I was too polite to say something like “How the hell should I know?” Far more polite than Hurston would be if she could now answer for herself. Yes, she made conservative, even reactionary noises in her lifetime against the NAACP, leftist politics, Richard Wright, and other socially progressive influences. But tagging Hurston as a libertarian or reactionary is far too reductive for such a

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2022

- review • March 1, 2022

Welcome to the Mar/Apr/May 2022 issue of Bookforum! In this edition, our contributors review new novels by Sheila Heti, Alejandro Zambra, Claire-Louise Bennett, and more, as well as newly reissued works by Kay Dick and Yūko Tsushima. The film critic A. S. Hamrah considers how director Billy Wilder bested the twentieth century, Sasha Frere-Jones reflects on essayist Lucy Sante’s inquisitive oeuvre, Harmony Holiday writes about the late hip-hop producer J Dilla’s poetics, and so much more. Read the issue online here, and consider signing up for or gifting a subscription.

- print • Mar/Apr/May 2022

ARTHUR JAFA RELAYS A HAUNTING INTERPRETATION of the griot as someone who cannibalizes the flesh of those whose stories he tells, as a matter of pragmatism, in order to keep those stories alive for the telling in himself. At the end of his life, the griot’s unsolicited efforts at preservation of both self and other are met with the same gesture: he is denied a traditional burial. His carrion is left out in the open air to be consumed by maggots, completing a loop or energy cycle in nature, which can be ruthlessly just and deliberate in its delivery of

- excerpt • February 3, 2022

About the time the playwright Lorraine Hansberry returned home to New York from Provincetown in the summer of 1957, a package arrived wrapped in plain brown paper. She had been waiting for it. Inside were copies of One: The Homosexual Magazine. One was sold mainly by subscription, because not many newsagents would have dared sell it, and even fewer people would have dared buy it. It was considered “obscene material” by the US Post Office; hence the nondescript wrapping.

- excerpt • January 27, 2022

During the mid-1970s, Hunter S. Thompson was a central figure at Rolling Stone magazine. Although he did not write about music, he was its most popular contributor, and Abe Peck observed his primacy at close range. After editing an underground newspaper in Chicago, Peck worked for Rolling Stone in the mid-1970s and later taught journalism at Northwestern University. In his estimation, Rolling Stone was one of the most important American magazines of its era, and Thompson defined its nonmusical voice during the 1970s. In particular, Thompson linked readers to their youthful iconoclasm even as their tastes changed. “He kept the

- excerpt • January 3, 2022

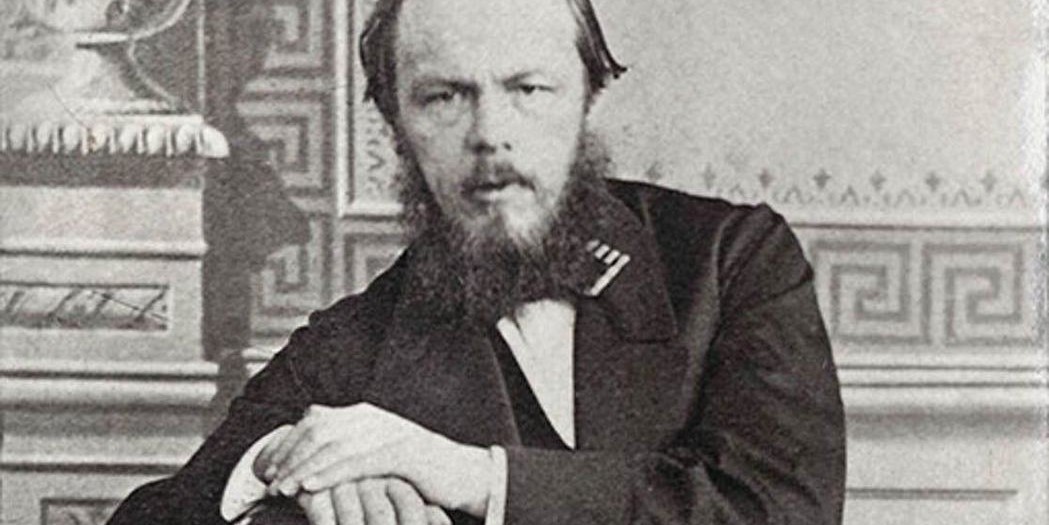

Eyes fixed on the Bulgarian editions of The Idiot (1869), Demons (1872), and The Brothers Karamazov (1880), my father advised me strongly against reading them: “Destructive, demonic, clinging, too much is too much, you won’t like him at all, let it go!” He dreamed of seeing me escape “the bowels of hell,” as he called our native Bulgaria, quoting some obscure verse in the Holy Scriptures. To fulfill this desperate plan, I only had to develop my “innate taste” for clarity and freedom, according to him, in French, of course, since he had introduced me to the language of La

- review • December 14, 2021

Greg Tate, a longtime contributor to the Village Voice and other publications, died last week. Here, four critics pay tribute to Tate’s influential, hyper-referential, bumptious, and generous writing and conversation.

- excerpt • December 9, 2021

In the United States in the mid-1960s, a case came before the Supreme Court, one intended to settle the question of obscenity addressed by the famous Roth decision of 1957. The nine quarrelsome old men now came to the conclusion that obscenity required a work to be utterly without any redeeming social value. Whammo! There was a thoughtful pause whilst the country digested that—and came to the conclusion that of course there was a revelatory and redeeming social value to even the lousiest suckee-fuckee books. The gates were opened. The flood began. Suddenly all the old four-letter words (and

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2022

IN STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION, THE ANDROID DATA starts to dream, having accidentally discovered an unconscious he didn’t know he had. Soon, because his dreams are troubled, he enters psychoanalysis. Appropriately enough, he turns to another artificial intelligence for help, the computer of the starship Enterprise, which creates a holographic representation of Sigmund Freud. Later, Data dreams that he is on the Enterprise, standing with two of his companions. A phone rings. But where is it? Data’s friends open a hatch in his abdomen. An early-twentieth-century phone stands there, waiting for someone to answer; when picked up, the phone

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2022

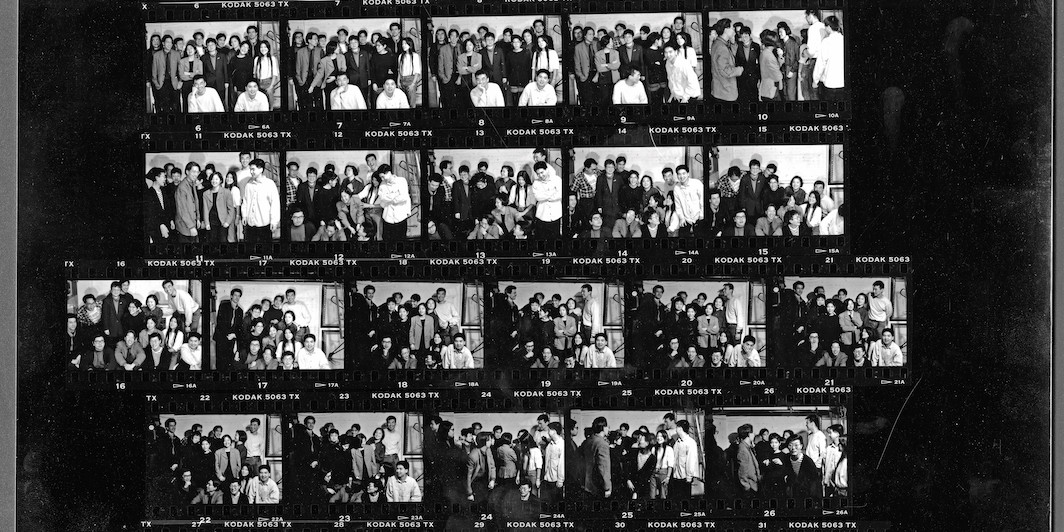

FOUNDED IN 1990, GODZILLA was a New York–based collective of visual artists and curators that sought “to contribute to change in the limited ways Asian Pacific Americans participate and are represented in a broad social context.” Early in the new anthology Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network 1990–2001, there’s a spread of contact sheets showing outtakes for a group picture taken in 1991 for the collective’s first newsletter: we see bodies shuffling, awkward hand placements, ill-timed smiles, and aching cheeks. The sequences illustrate the momentary coalescence—flash!—and then the release, the laughter as the image crumbles back into the disorder of life.

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2022

WHAT’S COMMONLY KNOWN ABOUT THE PORTUGUESE WRITER FERNANDO PESSOA is that he died young-ish at the age of forty-seven in 1935, drank heavily, and assigned authorship of his work to over a hundred “heteronyms,” pen names that carry more biographical heft than the average alias. Pessoa died having published only one book of poetry in Portuguese (Mensagem) and two self-published chapbooks of English-language poetry. The lion’s share of his work was found in a trunk containing about 25,000 pages of writings. Without much of a public record of his life as he lived it, celebrating Pessoa and researching Pessoa have

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2022

I WOULDN’T DARE COMPARE MYSELF to the legendary actor and singer Billy Porter, but if you were trying to cast a show, circa 2009, we would definitely be up for the same part. Both of us queer, both of us Black, we came to theater—acting, writing, and directing—through music and musicianship, gifts spotted early and cultivated in high school. Both of us have a freakishly high singing voice, although Billy’s is touched by an angel, and mine is more like a fun party trick. This is about where our similarities end, really, but in the business of show, that was

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2022

IN THE FALL OF 1866, FYODOR DOSTOYEVSKY FOUND HIMSELF barreling toward every writer’s worst nightmare: a deadline he couldn’t ignore. Having signed an ill-advised contract to avoid a trip to debtor’s prison, he now owed the publisher Fyodor Stellovsky a new novel of at least 160 pages by November 1. If he failed to deliver, Stellovsky would be entitled to publish whatever Dostoyevsky wrote over the next nine years free of charge. A more practical man might have spent his summer on the project for Stellovsky, but Dostoyevsky was simultaneously preparing segments of Crime and Punishment for serialization, and his

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2022

Reza Abdoh, Quotations from a Ruined City, 1994. Performance view, New York, February 1994. Brenden Doyle. Abdoh: Paula Court/Courtesy Paula Court. “Reza Abdoh arrived like a rumor.” So begins the introductory letter from Bidoun’s Negar Azimi, Tiffany Malakooti, and Michael C. Vazquez, the editors of REZA ABDOH (Hatje Cantz/ARTBOOK DAP, $55), a riotous, near-narcotic immersion […]

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2022

IN 1990, WHILE COLLECTING PERSONAL PHOTOGRAPHS for their Ohio River Portrait Project, archivists at the Kentucky Historical Society came upon an amusing, near-century-old snapshot commemorating something called the “Tacky Party” of Ballard County. Seven turn-of-the-century young adults pose for a group portrait, looking as genteel and deadpan as a team at the beginning of a Family Feud episode. They first appear to be wearing the usual sorts of garments we might picture when we think of the early 1900s: hats piled high with ornamental flowers and ribbons; billowing, floor-length dresses with lacy, chin-skimming necklines. But upon closer inspection, the modern

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2022

Amiri Baraka, Newark, New Jersey, 1959. Burt Glinn; © Burt Glinn/Magnum Photos. BROOKS BROTHERS USED TO MAKE UNIFORMS FOR SLAVES, you know. It’s true. The company supplied the mid-twentieth-century Ivy League uniform of oxford-cloth shirts, boneless three-button suits, and chunky cricket sweaters primarily because they were known to make good clothes. (Die-hard partisans, however many […]

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2022

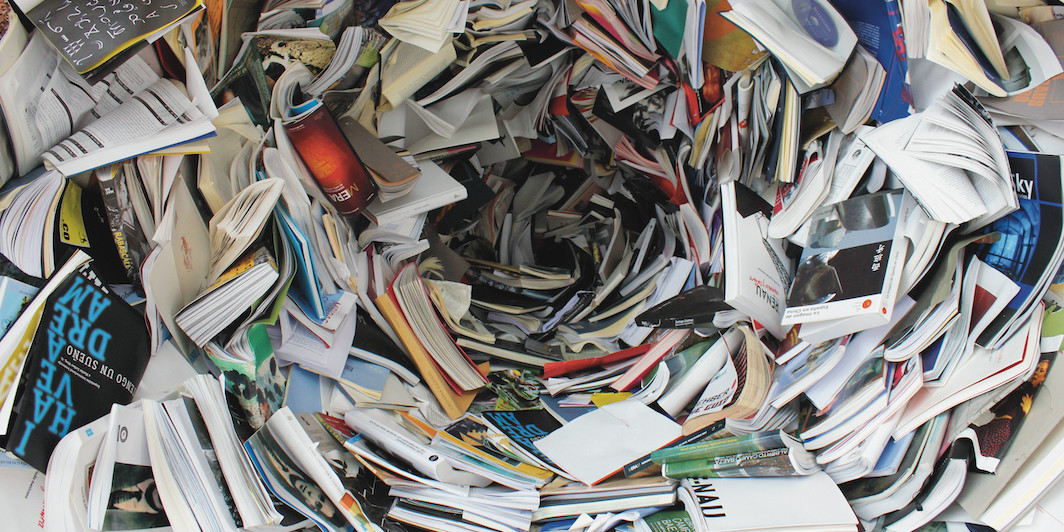

DWINDLING ENLISTMENT AMONG STUDENTS and deteriorating market share among consumers; confusion as to immediate method and cloudiness as to ultimate mission. . . . Professors of literature have good reason to feel insecure about the status of literature and literary scholarship. And, like many an insecure person, the discipline of literary studies has grown increasingly interested in and respectful of popular taste as its own popularity has declined. Between the Great Recession and 2019, the number of undergrads majoring in English shrank by more than a quarter, and it’s difficult to imagine the pandemic has reversed the trend. Meanwhile, over

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2022

DEPRESSION, FOR ALL THAT HAS BEEN WRITTEN ABOUT IT, remains in many ways a voiceless illness. If depression were an actor in a play, it would be one without words, its presence a reminder that psychic darkness isn’t invisible so much as carelessly—or, as it may be, willfully—overlooked. Since time immemorial, clinical depression—the kind that sometimes ends in suicide—has not been given its due as a legitimate ailment, with claims on our attention and concern every bit as much as cancer. Like many psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia, the ratio between biological determinants and psychodynamic ones has never been firmly established,

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2022

IT TOOK ONLY A COUPLE MONTHS after moving to Memphis for me to realize I was living in a necropolis. You have Elvis’s Graceland temple by the airport; the solemn Lorraine Motel where Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered; a famous cemetery where Isaac Hayes and Sam Phillips are buried and—in case you’re still doubting my assessment—downtown’s hulking black Bass Pro Shops pyramid, where the redneck pharaohs await the endless hunting and fishing of the afterlife. Sometimes I’d feel I was walking not through a city made for the living, but a temple compound dedicated to gods that can’t hear

- print • Dec/Jan/Feb 2022

Shahzia Sikander, Pleasure Pillars, 2001, vegetable color, dry pigment, watercolor, and tea on wasli paper, 17 x 12″.© Shahzia Sikander/Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly, New York/Collection of Amita and Purnendu Chatterjee. UPON HER ARRIVAL at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1993, Pakistan-born artist Shahzia Sikander was asked by an instructor if she […]